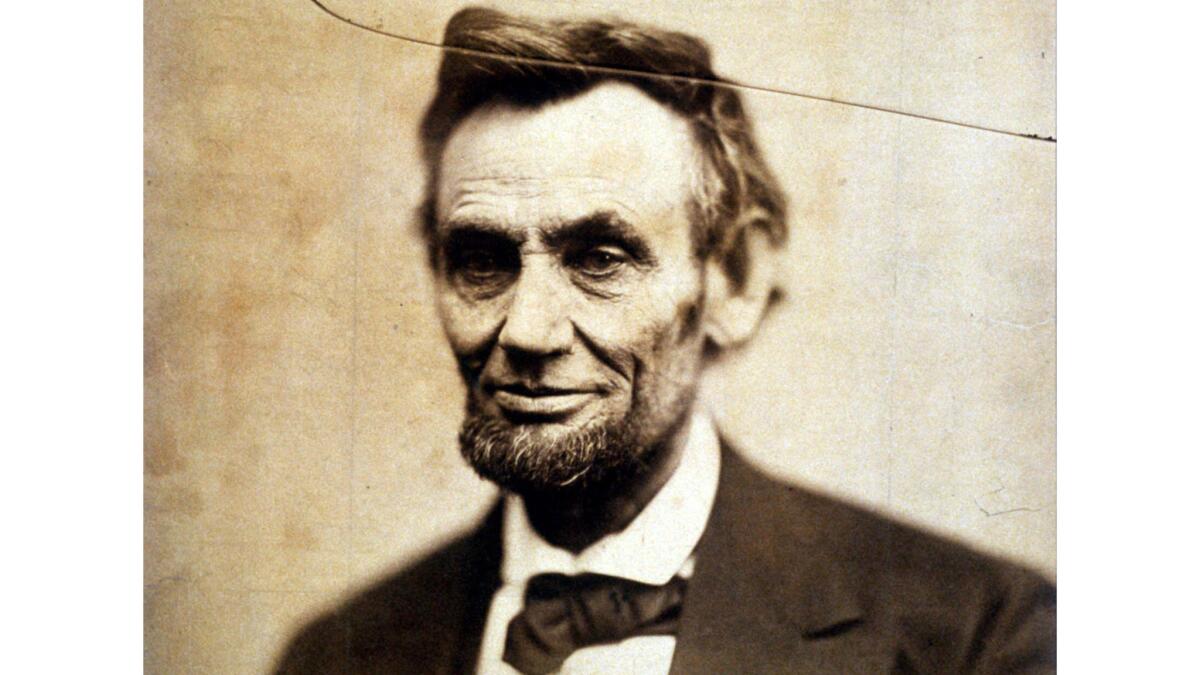

Abraham Lincoln’s early life is recast by Sidney Blumenthal in the masterful ‘Wrestling With His Angel’

- Share via

Writing editorial columns. Refining his views on slavery. Condemning the Kansas-Missouri Act. Keeping a wary eye on Stephen A. Douglas and then tormenting him on the issue of popular sovereignty. Studying Euclid. Wrestling with the remnants of the Whig Party and then constructing the contours of the new Republican Party. In short, becoming Abraham Lincoln.

In the second volume of his massive political life of Lincoln, the Democratic operative and writer Sidney Blumenthal sketches a Lincoln in the wilderness — after his single term in the House, before his landmark Senate campaign against Douglas — that challenges the established notion that for more than half a decade the future president sat quietly and idly in Illinois, more a passive observer than an activist as his party, his vision of America and his country split apart, tumbling to civil strife and then to civil war. Lincoln was not only seeking a newer world, as Tennyson put it in a poem written a decade earlier, or the way to assemble one. He was also seeking his main chance.

Much of the prevailing view of Lincoln in this period (1849-1856) is from William Dean Howells, who portrayed Lincoln as “[s]uccessful in his profession, happy in his home, secure in the affections of his neighbors, with books, competences, and leisure — ambition could not tempt him.” Lincoln tolerated, even fostered, that view, as a counterweight to the notion that, as an Illinois newspaper put it at the time, “Lincoln is undoubtedly the most unfortunate politician that has ever attempted to rise” in the state.

“Wrestling With His Angel” challenges and changes all that. In a book that barely introduces the main character of the narrative until page 129, Blumenthal argues that Lincoln “entered his wilderness years a man in pieces and emerged on the other end a coherent steady figure.”

This Lincoln lost a child, and his tortured wife, Mary, descended into depression, panic attacks and migraines. He toiled as a lawyer, traveling across the plains in a buckboard wagon, often working for the railroads, once having to sue for his fee because the company superintendent refused to pay it. This superintendent’s name was George B. McClellan. The two would collide again, eventually with President Lincoln firing Gen. McClellan, then with the embattled incumbent chief executive defeating Democratic presidential nominee McClellan for the White House.

Uneducated in the traditional sense, Lincoln nonetheless was educated in the classical sense. Much of that education occurred in this period, a good deal of it focusing on Eucild’s “Geometry,” which Lincoln applied directly to his thinking, then to his arguments, especially his critique of Douglas, which provides the main spine of this volume: “a series of ironclad logical proofs,” Blumenthal argues, “on the geometry of slavery and against its extension.”

Always in this period Lincoln was preoccupied with Douglas, who dominated Illinois politics and was, like Sen. Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts more than a century later, regarded as the president next time but never the president this time. And he was obsessed by the politics that divided the country that he traversed as a circuit lawyer, a passion stoked by the American tour of Louis Kossuth, the romantic symbol of the Hungarian revolution for freedom of 1848.

What comes across clearly in this volume is that even in their early obscurity, Lincoln and Douglas were Illinois rivals, though the struggle between the two was seldom a fair fight, for Douglas was so much more polished, so much more eloquent, so much more powerful. Of this Blumenthal writes: “His longtime principal rival within his home state, the leader of the Whigs there, had served only one term in the Congress and was now riding a horse on the dusty trails of the Eighth Judicial District of central Illinois; nobody remembered his name.”

One of the principal lessons of this volume is the difference a decade can make — think of the contrast between 2007, when another Illinois politician, Barack Obama, was on his ascent, and 2017, when Donald J. Trump sleeps in the White House — especially when, in their time as in ours, events moved at a gallop or, to appropriate a loaded modern term, at warp speed.

In 1850 the country was dominated by the Great Triumvirate of Clay, Calhoun and Webster. By mid-decade the three were gone and Douglas was the man of the hour. By the end of the decade Lincoln would be elected president and the Compromise of 1850, which was supposed to render the issue of slavery moot forever, was itself in tatters, along with the country it was designed to save. The “convulsion” — the word was Daniel Webster’s — the compromise was supposed to avoid resulted in the “dismembership of this vast country” that Webster dreaded. He was right, but so was John C. Calhoun, who answered Webster by saying, “Disunion must be the work of time.”

It was Douglas and the controversial Kansas-Nebraska Act that drew Lincoln back into politics for good — the double meaning of the phrase here is intended — and before long he was giving speeches and writing what we today would call op-ed columns. “In 1854,” Lincoln wrote in his 1860 campaign autobiography, “his profession had almost superseded the thought of politics in his mind, when the repeal of the Missouri compromise aroused him as he had never been before.”

Lincoln followed Douglas like a shadow, trailing him, taunting him, haunting him and, according to Blumenthal, “found him unexpectedly vulnerable.” For it was geography — their shared turf of Illinois — that transformed Lincoln, and not Charles Sumner or Salmon P. Chase or William H. Seward, into Douglas’ prime rival and antagonist. “Douglas contended with all the powers-that-be in Washington, yet inevitably he had to return to earth — to Illinois,” Blumenthal writes. “While playing for the greatest national stakes, his base of support, his organization, and his right to office were rooted in his home state.”

And Blumenthal argues that while the political arts may not have been his formal profession, politics was never far from Lincoln’s mind, nor from his activities, nor surely from his talents. Blumenthal achieved national attention with his work with Bill and Hillary Clinton, who prided themselves in dividing their lives into “little boxes.” Not so Lincoln. “There was not a double Lincoln, split between the lawyer and the politician,” writes Blumenthal, whose view of his historical subject was almost certainly shaped by his experience with his contemporary patrons. “Whatever he gained in sharpening his method as a lawyer he knew or hoped he would apply in politics. For him the courtroom and the campaign were transferable arenas. His speeches in both were addressed to the jury.”

The result, according to Blumenthal: “a river of logic, history, metaphor, allusion, storytelling, and emotion that flowed until he finally ended Douglas’s ambition.”

But this ultimately is the story of the redemption of Lincoln’s ambition, and in these pages we see the green shoots of the mature Lincoln — the notion, first, that his priority was saving the Union rather than eviscerating slavery; then the image, borrowed from the New Testament, of a house divided; and, finally, the rhetorical use of the preamble of the Declaration of Independence as a touchstone for his creed. What Blumenthal sets out in “Wrestling With His Angel” is really “The Making of the President” — of President Abraham Lincoln and of the nation that a man without religion (but suffused with faith and religious imagery) would help become born again.

David Shribman is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

“Wrestling With His Angel: the Political Life of Abraham Lincoln Vol. II, 1849-1856”

Sidney Blumenthal

Simon & Schuster: 608 pp., $35

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.