Taylor Swift joins Rilke in Michael Robbins’ ‘Equipment for Living,’ reviewed by Justin Taylor

- Share via

“Criticism is parasitic literature,” writes Michael Robbins, the poet and critic, in his new book, “Equipment for Living: On Poetry and Pop Music,” a collection of his recent criticism, which I in turn have been tasked with criticizing. Where to start?

Maybe best to begin with Robbins himself. An English PhD who mostly eschews traditional academic scholarship, he’s the author of two collections of poems, “Alien vs. Predator” and “The Second Sex.” You may have noticed that both titles are borrowed. The original “Alien vs. Predator” was a movie, the first installment in what became a very bad and successful franchise, though the word “original” is a bit fraught here since the film is itself a mash-up of two older sci-fi franchises that each started strong then devolved into badness. Before “The Second Sex” was Robbins’ book of cantankerous, hilarious and densely allusive poems (with titles cadged from Warren Zevon and the Grateful Dead), it was a foundational piece of feminist criticism published by Simone de Beauvoir in 1949.

This should give you a sense of the sweep of Robbins’ interests and of his investment in sampling, mash-up and parody — all parasitic creative forms — as central elements of his practice. “Originality, fetish object of the young and naive, is no virtue in itself,” he writes in an essay called “Rhyme Is a Drug.” “If it were, every free jazz collective, no matter how inept, would be superior to the Rolling Stones.”

The essay collection borrows its title from Kenneth Burke, who said that poetry was “part of the consolatio philosophiae […] undertaken as equipment for living, as a ritualistic way of arming us to confront perplexities and risks.” Robbins adds to the mix a dollop of Nietzsche, a dash of Harold Bloom (the good Bloom: the Romantic-Freudian, not the preening neo-con), and a few lines of Geoffrey Hill’s: “What / ought a poem to be? Answer, a sad / and angry consolation.” (The italics, by the way, are Hill’s borrowing from Leopardi — it really is turtles all the way down.) All this to clarify that, for Robbins, “Consolation is not false comfort. Poetry’s a prophylactic, not a vaccine. One way poetry helps you to accept perpetual unrest, to arm yourself to confront perplexities, is by reminding you you’re not alone (a not coincidentally common refrain in popular song).” And so the book’s two primary concerns twine together like the double helix of the DNA strand, which I wish I could avoid mentioning forms our own most fundamental equipment for living, but this is the corner into which I’ve painted myself, so there you have it. Moving on.

On record, the song is one of her best, but on that night, on my television screen, for as long as it lasted, it was the best song I’d ever heard.

— Michael Robbins

Despite the fact that most of these pieces were written for newspapers and first published as book reviews and blog posts, the collection holds together remarkably well as a collection. Certain signal concerns — Rainer Maria Rilke and John Ashbery, Journey and Taylor Swift — appear and reappear, like motifs, as do a handful of beloved forerunners and fellow travelers: Greil Marcus, Ellen Willis, Pauline Kael, Joshua Clover, Juliana Spahr, Anthony Madrid. Sometimes he’s citing their work and sometimes — especially in Clover’s and Marcus’ case — they’re sending him emails. (Sidebar: If you’re on Twitter, you should follow both Robbins and Clover, so you can tune in when they’re bantering. And in case it bears disclosing, I tweet with Robbins from time to time. We’ve both got super cute cats.)

“[T]he best criticism is always personal,” Robbins writes in an encomium to Kael. “What I want from criticism is that it make me think about art in new ways, or respond to things in it I hadn’t before.” This, he delivers. Here he is on Swift’s 2014 Grammys performance: “I think it was transcendent. Someone forgot to tell her the Grammys are a joke. She got her Stevie Nicks on, banging her locks and singing pretty much in key, hunched over the piano like a velociraptor and tearing the meat off its bones. On record, the song is one of her best, but on that night, on my television screen, for as long as it lasted, it was the best song I’d ever heard.”

Robbins is a guy who goes to the mat for what he believes in, whether its Marx’s theory of surplus value or a Basho haiku.

Robbins is erudite and meticulous, widely and deeply read, an agile thinker and a swift wit — but I don’t give a critic bonus points for having the qualities that constitute (or ought to constitute) the bar for entry to the profession. What I do give Robbins credit for, the thing that makes me want to talk about him the way he talks about Kael, Willis, et al., is the intensity of his enthusiasms. Most literary critics would be too self-conscious to write a passage like his Swift-swoon about their own favorite author, much less a millennial pop star. Robbins is a guy who goes to the mat for what he believes in, whether its Marx’s theory of surplus value or a Basho haiku, Hopkins’ “Spring and Fall” or Lana Del Rey’s “Honeymoon.” And when the intensity runs the other way, toward revulsion — look out, because dudgeon doesn’t get much higher. American poetry hasn’t seen this kind of Molotov-tossing since William Logan cut his hours back.

“If the worst are full of passionate intensity, Simic would seem to be in the clear,” he writes in “How to Write a Charles Simic Poem.” “[W]hat I hate most about [Dylan] Thomas: if you care about poems, you can’t entirely hate him.” On a passage of James Wright’s: “It is easy to feel that, if fetal alcohol syndrome could write poetry, it would write this poetry.” This stuff is blistering, sure, and some might say ill-mannered, but criticism isn’t about good manners, or it shouldn’t be. I find myself heartened and refreshed by Robbins’ refusal to pull his punches or retreat into art-school gobbledygook.

And there’s more going on here than mere brutality, because Robbins has put the same intellectual and aesthetic care into his critical work as he puts into his verse. The Yeats allusion in the Simic zinger is a pretty easy pick-up, but it would take a real nerd (and boy am I ever your huckleberry) to notice that the James Wright line is a mocking revision of critic Denis Donoghue’s 1983 praise for Stephen Mitchell’s translations of Rilke.(“It is easy to feel that if Rilke had written in English, he would have written in this English,” Donoghue wrote. Robbins, who can’t help loving Rilke despite finding him to be “mannered mush,” is a partisan for the Edward Snow translations. I share his abashed affection for the poet but fly my banner for House Mitchell in the wars.)

Few readers will agree with all of Robbins’ assessments, and some of his battles may strike you as not worth fighting. That’s as it should be. To me, a seemingly endless exegesis of “Frederick Seidel’s Bad Taste” felt like alienated labor. Sure, Robbins makes the best case likely to be made for the method and significance of Seidel’s neo-Sadean depravities (leaning heavily on Adorno and Nietzsche; you can hear them groaning under the weight) but he never does get around to saying that he actually enjoys the stuff, and for such a reflexive enthusiast the omission is not just glaring but telling. But as Robbins himself writes, “we return to the critics we love for reasons that, it may be, have little to do with movies (or literature or music or architecture) and everything to do with the play of wit and insight and the construction of sentences.” That’s emphatically, even ecstatically, the case with “Equipment for Living,” which insists at every turn that despite its inherent parasitism, criticism is a creative discipline — a venue for originality and exploration, for agon and jouissance. In short, an art form. I only wish more critics would follow his lead.

Taylor’s most recent book is the story collection “Flings.” This year he is a visiting writer at the University of Southern Mississippi.

“Equipment for Living: On Poetry and Pop Music”

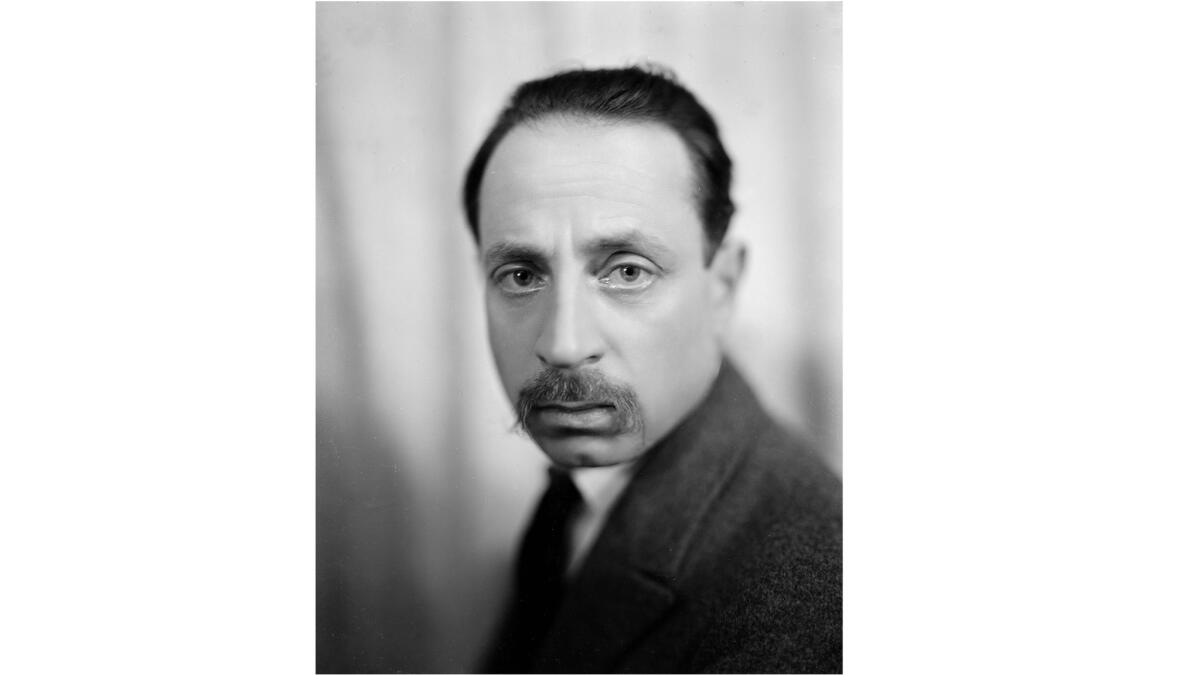

Michael Robbins

Simon & Schuster: 224 pp., $24

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.