Review: How Hollywood scandal was born

- Share via

In its regular roundup of celebrities caught in public performances of latte-sipping, stroller-pushing everydayness, US Weekly assures its readers that stars are “just like us!” But why would we want stars, those shiny embodiments of melodrama and talent and glamour, to be just like us? Why demand authenticity from those so skilled at seeming larger than life?

Anne Helen Petersen has spent the last few years making these questions relevant, as the Internet’s most dependable guide to the ways celebrities harness and challenge American culture’s ever-shifting understanding of race, class and gender. At her blog Celebrity Gossip, Academic Style, Petersen — who wrote her doctoral dissertation on the history of the gossip industry — has explored phenomena like the genre of “postfeminist dystopia” and the “True Detective”-era “McConnaissance,” and on websites like the Hairpin and her new full-time perch at BuzzFeed, she’s published authoritative cultural histories of Entertainment Weekly, TMZ and the celebrity profile itself.

“Scandals of Classic Hollywood,” her first book, chronicles the making and unmaking of several leading lights from the height to the eclipse of the studio era. It’s structured as a series of star mini-biographies, but when recounting the familiar railroading of Fatty Arbuckle or the turbulent career of Judy Garland, Petersen is less interested in compiling a history of Hollywood’s juiciest scandals than in detailing how stars and their studio fixers have managed ruptures to their carefully pruned and highly valuable image. Collecting fabricated anecdote and “well-circulated legend” along with biographical fact (while careful to distinguish between them), Petersen repeatedly suggests that in the marketplace of celebrity gossip the plausible is never the enemy of the true.

“Scandals” is an episodic but exhaustive study of the Hollywood studio system that puts public relations on equal footing with film aesthetics and makes a strong case that narratives of stardom can be more tragic, ironic and savagely entertaining than the movies that prop them up.

From a star studies point of view, movies become vessels for the star image, not the other way around. So while film historians might cherish “To Have and Have Not” as early evidence of the continued mastery of director Howard Hawks and literary critics might appreciate the novelty of Faulkner adapting a Hemingway novel, Petersen contextualizes the 1944 romantic thriller as a PR tool to sand the edges of the budding illicit romance between the older, married Bogart and ingenue Bacall. “If the two had met in Hollywood and started dating, it would’ve … reeked of lechery and could have permanently affected their images. Instead, their introduction as a couple was within the narrative of a film — a film in which they seemed not only believable but, again, natural as a couple.”

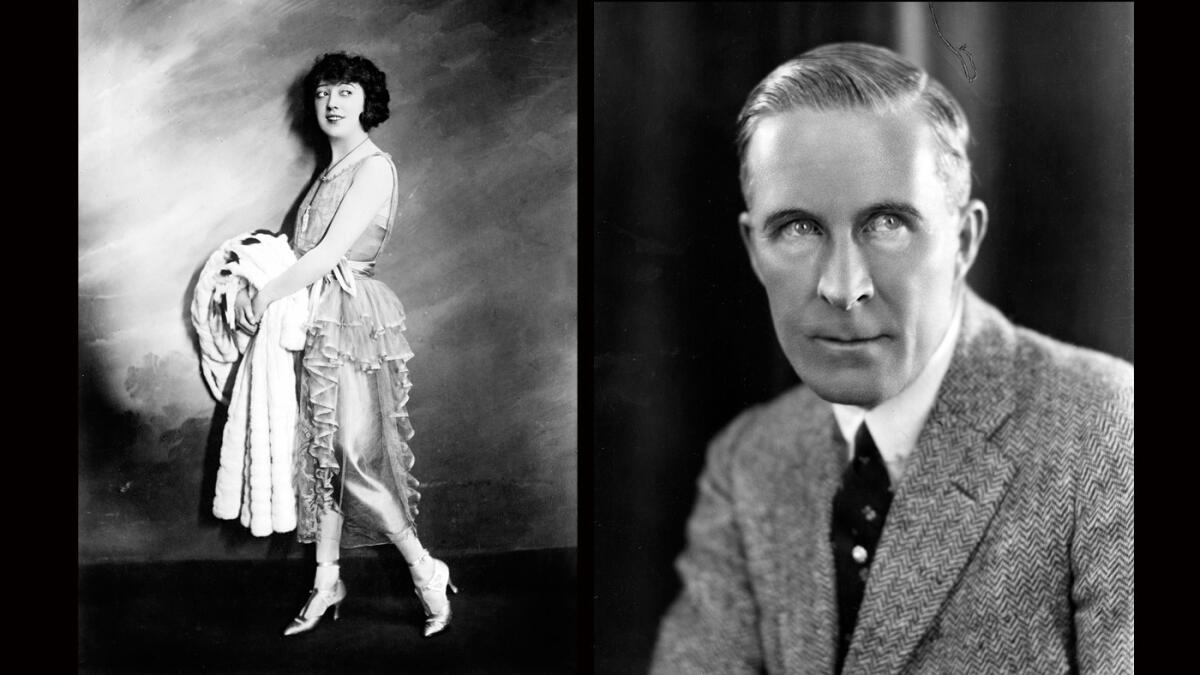

In particularly strong chapters on Clara Bow, Dorothy Dandridge, Jean Harlow and Mae West, Petersen is attuned to the ways the celebrity female body can serve as an unwitting battleground for societal discomfort about sex. Contemporary tabloids make it clear that not much has changed.

Although Petersen’s book benefits from intelligent analysis of archival research, she writes with the verve of an enthusiast. Scandals can feel limited by its quick-hit structure — you’ll want more than 10 pages on James Dean — but these stories’ cumulative message is clear and convincing: “Stars are manifestations of conflicting societal and cultural impulses,” Petersen writes, and we label their scandals trashy because we’re afraid of what our fascinations reveal.

For those ready to yield to these fascinations, film historian William J. Mann offers “Tinseltown,” a sprawling, deliciously decadent recounting of (and possible solution to) one of Hollywood’s legendary unsolved mysteries, the 1922 killing of director William Desmond Taylor.

The rise of the movies was accompanied by widespread fear of moral decay, so bad publicity could seriously jeopardize the industry’s fortunes. Thanks to well-organized civic reformers and “church ladies” brandishing crucifixes, the threat of systematic censorship loomed. The killing of Taylor, a silent film star turned Paramount director who became the upstanding president of the Motion Picture Directors Assn., struck many as a confirmation of every tawdry rumor about the “film colony.”

Mann has serious credentials as a Hollywood historian, having penned biographies of Barbra Streisand and Katharine Hepburn and 2001’s “Behind the Screen: How Gays and Lesbians Shaped Hollywood,” and can navigate the haze of intrigue and ambition that separates “Tinseltown” from Los Angeles. He’s also a veteran novelist who revels in thick description: The resentment of a group of lost souls is “left to bake inside those cramped, stuffy rooms, pulsing off the stucco walls like heat from an oven on a sultry afternoon.”

Packed with period flourish and outsize personalities, Mann’s propulsive, gripping history revels in the details that Petersen studies and scours the underside of movieland to cover a pulpy terrain of contraband booze, organized blackmail, bunco schemes and “white slavery.” “Tinseltown” doles out information with an eye toward suspense: Every short chapter ends with a cliffhanger, then immediately shifts the setting to unspool another thread.

The book doubles as a biography of the ruthless striver Adolph “Creepy” Zukor, an orphaned Hungarian immigrant with a 10th-grade education who developed a handful of penny arcades into the empire of Paramount Pictures. Zukor saw the early promise of moving pictures and used every tool at his disposal in his attempt to control the future of the industry, anticipate technological shifts and stave off federal regulation. Unscrupulous and inventive, he took the lead in minimizing the damage from the Taylor killing. In uncovering the secrets of the case, the book also concentrates on the fortunes of three desperate starlets in Taylor’s orbit, all of them eventual suspects. Stranded on different rungs of the showbiz ladder, the actresses struggle to take the next step while dodging several forms of scandal.

“Tinseltown” is entertaining enough to feel illicit, but its reporting makes it an essential addition to any respectable bookshelf of L.A. history. Mann seamlessly draws together material from recently released FBI files, police reports, telegrams and newspapers. Though several books and a hundred-issue fanzine have Talmudically scrutinized the Taylor killing, none have reached the same compelling conclusion that Mann does.

The perennial allure of a movieland mystery and the obsession over details and motives seems generated by the same curiosity that makes someone an Us Weekly subscriber. We want to make sure the movie never ends, and we want to be part of it. For these books, that’s what makes us “us.”

Gottlieb writes about film for the Nation and lives in Los Angeles.

Scandals of Classic Hollywood

Sex, Deviance, and Drama From the Golden Age of American Cinema

Anne Helen Petersen

Plume: 304 pp., $16 paper

Tinseltown

Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood

William J. Mann

HarperCollins: 480 pp., $27.99

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.