What Shakespeare & Co. taught me about being a writer

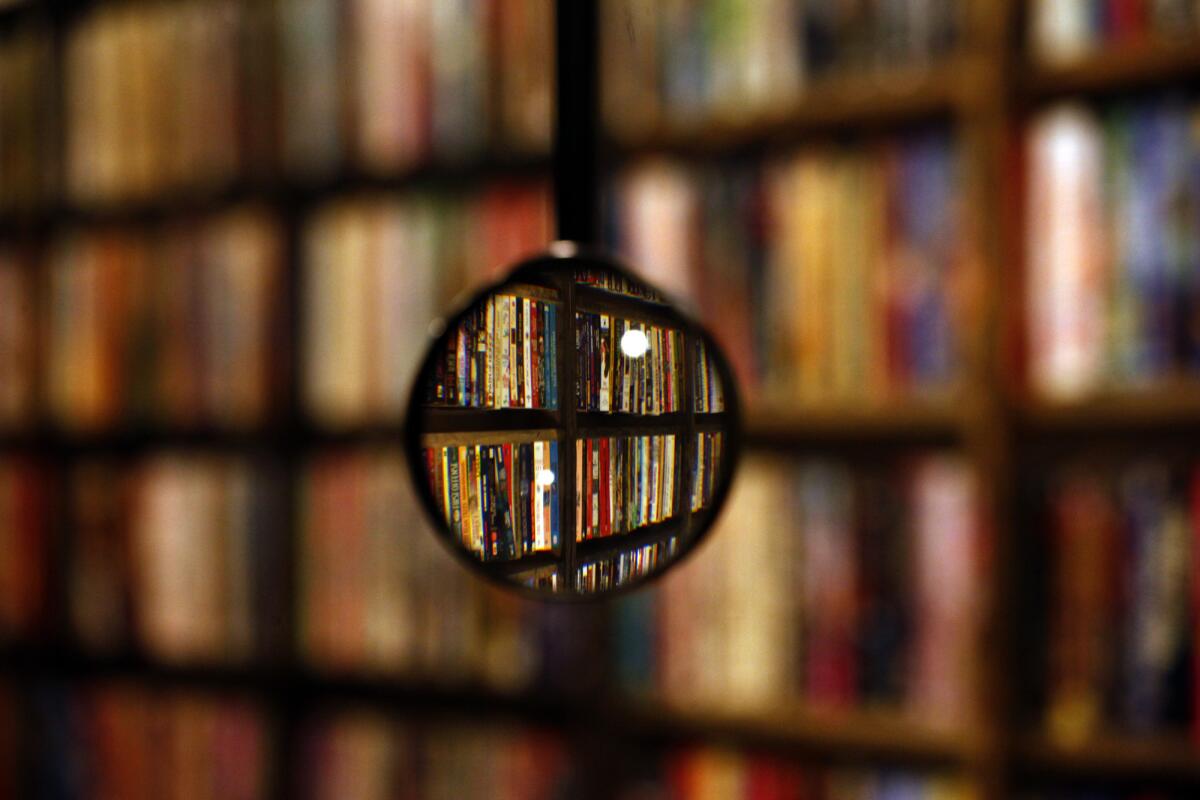

I learned how to be a writer at Shakespeare & Co. on lower Broadway in Manhattan. This was in 1987, when I was in my 20s, and trying to figure out how to be a writer in the world. I had been working the buy-back desk at NYU bookstore when I learned Shakespeare & Co. was opening a downtown branch. My first day of work was in an empty bookstore, in which the shelves, still covered in sawdust, had just been installed.

Now, that store, which I helped open, is going out of business, priced out by rising rents. According to the website Gothamist, the doors will close at the end of this month, leaving Shakespeare & Co. with just one location in New York, on the Upper East Side.

There are a variety of ways to read this story, most obviously as a lament for what Gothamist calls “the soon-to-be-extinct joy of turning a real, paper pages.” This, however, is misleading.

Since 2009, the American Booksellers Association reports, the number of independent bookstores in the United States has increased 19.3 percent, from 1,651 to 1,971. In New York, the venerable St. Mark’s Bookshop has just moved into a new space in the East Village, and the Brooklyn bookstore scene is thriving, with, among others, Word, Community Bookstore and Greenlight.

In that sense, the demise of Shakespeare & Co. may be less emblematic than individual, a situation unto itself.

For me, though, who dusted those shelves in the weeks before the store opened and then loaded them with books, alphabetizing the fiction section, it is personal, a death in the family.

I spent a year-and-a-half working at Shakespeare & Co., first as a clerk and later as front list coordinator. I sat in on ordering meetings with publisher reps and decided what went in the front display window. I chased thieves and offered advice to customers, wrote short stories and poems while working bag check or sitting at the information desk. I made friendships that lasted for years after I quit to write full time.

What bound us together was a love of books, of literature; we were always reading in that store. We were also always hosting writers, particularly those who were then emerging from the East Village: Joel Rose, Catherine Texier, Patrick McGrath, Lynne Tillman, Susan Daitch. These were the first writers I ever got to know, and there was something about the way they hung together and supported each other’s work.

I had always considered writing a solitary pursuit, which it is — you sit in a room alone for hours, staring down the brutal emptiness of the page or screen. But it is also, this group of writers taught me, a function of community. When I was lamenting, one day in early summer, my inability to get published, one of them suggested I try book reviewing. It’s easy to get book reviews published, he said.

That someone would be able to say and mean this — and that it turned out to be true — suggests how long ago that conversation happened, but from the perspective of the present, this is not what resonates.

Rather, the most important aspect of the experience is the sense I had that I was being treated seriously, that an older author was taking interest, offering advice. For the first time, I felt as if I were being mentored, as if I was part of something bigger than myself.

This is one of the things writers, all artists, are supposed to do, to help bring along the next generation, to operate as part of a continuum, to build a scene. That this is less possible than it once was goes without saying, but that doesn’t mean it’s not still essential, one of the commitments of community.

Working at Shakespeare & Co. taught me that, in the best way such lessons are transmitted: by example. It was my first literary clubhouse, the place where the idea of being a writer went from being abstract to concrete. Partly, this had to do with the books, with the constant, heady conversation, but even more with the people — those who worked there, and those who drifted in.

It has been 25 years since I last worked there, but the memories remain fresh. And so, this week or next, when Shakespeare & Co. closes for the last time, I will feel (I feel already) as if I have lost a piece of myself.

Twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.