It’s not your grandma’s Book of the Month Club

- Share via

Before Oprah Winfrey anointed bestsellers with her book club picks, there was the Book of the Month Club. And now it’s coming back for another round.

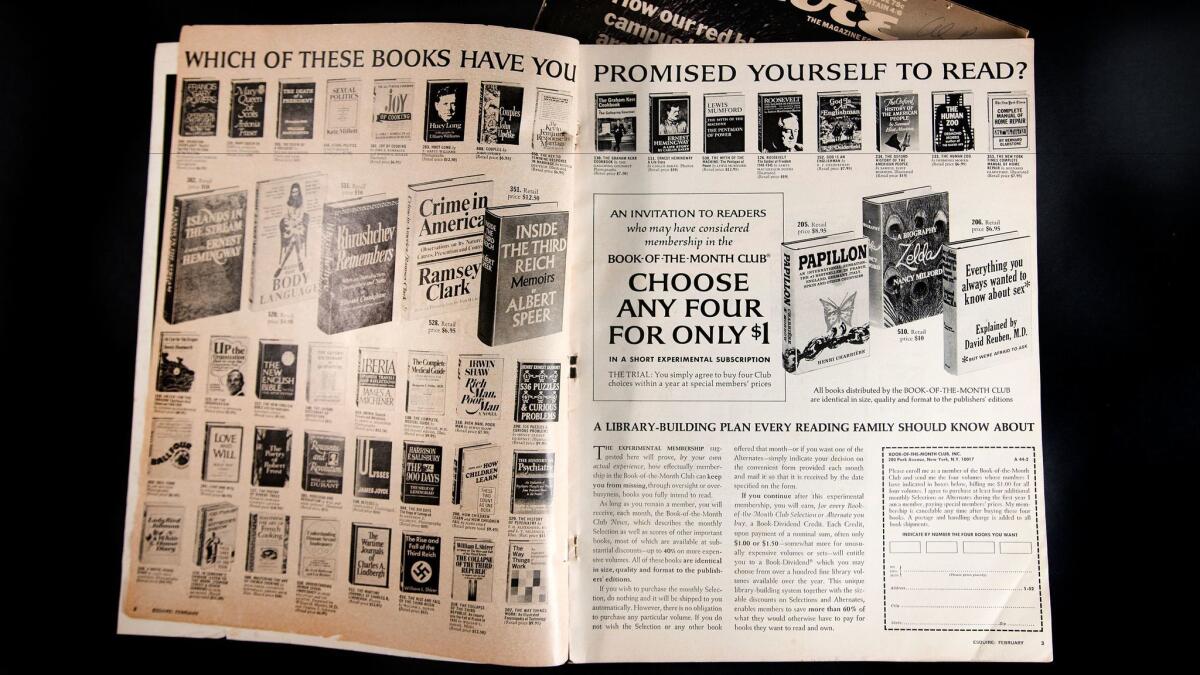

The Book of the Month Club, a pioneer of book distribution and marketing, relaunched late last year with a new approach and new attitude. The reboot makes a nod to the storied firm’s 90-year history in mail order book sales but concentrates more on the future rather than its, at times, controversial past.

“It’s still the same company, but our priorities have changed a lot in the last couple of years,” club editorial director Maris Kreizman said in a recent email. “We’re very focused on leveraging technology to deliver incredible member experiences online.”

With more than 112,000 followers on Instagram and over 100,000 likes on Facebook, the Club is fueled partly by an active presence on social media. Members regularly post photographs of themselves — or their pets — with their purchases. Also popular are “book bentos,” artsy photo displays of club books arranged with objects relating to their themes or subjects.

On the first of each month, the club website announces five “best” new releases along with detailed explanations of why the titles were selected. Members then pick which one they want to receive (if they don’t want to decide, the club will choose one for them).

Kevin Callahan, director of marketing at the Crown Publishing Group, has no doubts about the club’s ability to point members to books worth reading. “Maris Kreizman has earned a very strong reputation among readers and publishers as a taste maker,” he said. Kreizman, who has reviewed books for The Times, is the author of the “Slaughterhouse 90120,” which started as a blog. “You listen when she tells you there is a book you need to read.”

The transformation to an interactive, online experience was necessitated by fundamental shifts in the publishing industry since advertising executive Harry Scherman founded the Club back in 1926. At the time, a majority of Americans did not live near a bookstore or library. Books could be bought at drug and department stores, but selections were limited.

Scherman suspected there were millions of prospective readers across the country who would spend money on books if they were provided reliable information about new titles and a means of purchasing them. He had experience in mail-order marketing and thought its methods could be used to reach this untapped market.

His original concept for the Book of the Month Club was simple. He assembled a panel of literary experts to cull each month’s new releases and select a “best” title to be delivered to subscribers’ homes. It was a mail-order bookstore where the store decided what customers bought. He eventually tweaked the format to offer customers a discount and some choice in the titles they received.

For the club to operate profitably, it was imperative to keep costs low. Scherman accomplished this by producing club versions of the books rather than distributing the trade editions sold in stores. The discount version typically had smaller trim-sizes and used cheaper paper. As a result, volumes with the Book Club logo signaled “discount” and did not make ideal gifts or hold their value as collectibles. Even so, the revamped club quickly found a receptive audience. Within two years of the launch, over 100,000 people had subscribed.

According to Charles Lee’s 1958 book “The Hidden Public: The Story of the Book-of-the Month Club,” the publishing industry had a mixed reaction to the new enterprise. The American Booksellers Assn. initially supported Scherman, lauding him for helping people develop a reading habit and vigorously advertising the club’s selections.

Less enthusiastic were brick-and-mortar bookstore owners who worried about losing customers, and the publishers whose books were rejected by the club’s panel of experts. Rumors spread that the panelists rubber-stamped titles written by colleagues and those of publishers friendly with the club. Literary scholars joined the fray, criticizing the club for deeming itself an arbiter of literary taste.

Mounting a vigorous rebuttal, Scherman defended the integrity of the selection process and insisted the firm’s aim was not to hurt booksellers. Many naysayers eventually came around when the club did indeed seem to stimulate the entire book-buying market.

By the 1950s, the club had established itself as a respected industry leader with an eye for picking winners. Perhaps most famously, it touted “Gone With the Wind” to members well before critics and the Pulitzer committee anointed it 1936’s book of the year. While some critics sniffed at the club’s literary acumen — it passed on “The Grapes of Wrath” in 1939 — the business thrived over the next several decades because of its ability to feed an American public hungry for reading material.

The club’s impressive run of success hit a roadblock at the end of the 20th century. The marketplace for book-buying had altered radically since the 1920s. Imitator book clubs competed to satisfy the demand for books, as did national bookstore chains, big box stores, and online retailers. Also, readers had a wealth of resources where they could find book recommendations, such as the Internet, Oprah Winfrey and morning talk shows.

Despite various corporate transitions and adjustments to the format, the club failed to connect with a new generation of readers. It lingered for several years before finally ceasing operations in 2014.

The club relaunched in late 2015 as an online book subscription service. No longer needed as a lifeline to underserved markets, the revamp presents itself as a fun and reliable way to learn about new releases.

Assisted by a panel of judges made up of writers, editors, bloggers, and reviewers, editorial director Kreizman sifts through submissions from participating publishers to find the five “best” for the club’s members. The term “best” is used loosely, according to the website, to mean “immersive stories that transport you, give you thrills and tug at your heartstrings.” The literary pretensions of days past are long gone.

As in years past, members receive hardback books at prices lower than they would pay at most bookstores. The base rate for one book is $16.99, with additional discounts available for three-, six- or twelve-month commitments.

The club continues the practice of selling its own logoed editions. Not that Kreizman sees this as off-putting to readers. Today’s club editions are generally the same size as trade editions and “have some unique features like special endpapers and casings, and less advertising copy on the jackets.”

In addition to its social media feed, the club offers an online discussion forum where members can engage with other readers, the panel of judges, and sometimes even a selection’s author. Panelist Liberty Hardy raves about her interactions with members. “They are incredibly kind and super fun,” she said. “It’s amazing to answer people’s questions and hear their interpretations.”

Callahan sees a meaningful added value in the book club members’ online engagement. The “personal feel” of the Club community makes the act of reading less “solitary,” and a book becomes more than just something “to read and shelve.”

The majority of the club’s subscribers are women who seem to find community online while embracing the old-fashioned pleasures of physical books. “So much time is spent staring at various electronic screens these days,” said Kreizman. “People are looking to make some room for pauses in their life.”

Ellen F. Brown is a freelance writer whose work focuses on a wide variety of literary subjects, including publishing history. She is the coauthor of the book “Margaret Mitchell’s ‘Gone With the Wind’: A Bestseller’s Odyssey from Atlanta to Hollywood.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.