The pleasures of ambiguity: David L. Ulin on ‘Essayism’ by Brian Dillon

- Share via

“I like the idea of the essay as a kind of conglomerate,” Brian Dillon writes in his delightfully idiosyncratic “Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction”: “an aggregate either of diverse materials or disparate ways of saying the same or similar things.” The idea is that, for both readers and for writers, the essay defies a more coherent definition, that we are drawn to it because it cannot be pinned down.

This, of course, is a truism, which does not mean it isn’t true. At the same time, such semantic distinctions are beside the point. The essay takes its name from Montaigne: essai, Middle French for an attempt or try. It shares a Latin root with the English word assay. The essay, then, is an attempt to examine or analyze, to stake out a territory, which means it must be conditional, a set of impressions that circles back on itself.

“Essaying,” Dillon writes, “… is assaying. … The passages are many in which the great essayists announce (or denounce, because essayists are sometimes ashamed to be essayists) the tentative nature of their method or form.” I agree with all of that except the part about being ashamed to be an essayist. But what do I know? I work in the form.

Dillon’s book is itself a kind of conglomerate, which is to say it is an essay by another name. Opening with a lengthy (as in, two-page) sequential sentence, it wears its influences on its sleeve. This is among “Essayism”’s abiding pleasures, the author’s engagement as a reader — or better yet, the ongoing interaction between these two related modes. “On the death of a moth, humiliation, and how to write,” he begins; “what another learned about himself the day he fell unconscious from his horse.”

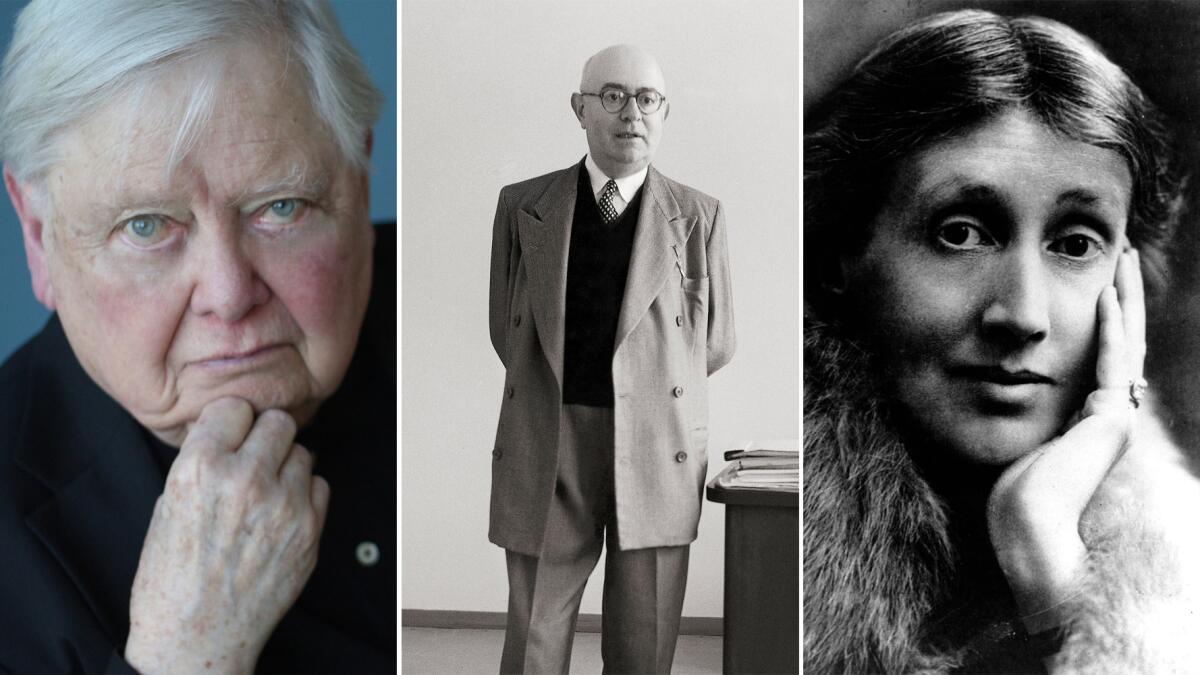

There they are: Virginia Woolf and Montaigne, while the sentence, the form of it, pays homage to William Gass. “The strangest and finest expression of Gass’s own listomania,” Dillon will later tell us, making the connection explicit, “comes at the start of his book-length essay ‘On Being Blue,’ published in 1976. I would love to quote it whole but it’s far too long, and in truth it is hard to know where the list ends: the entire book is a catalogue.”

Something similar is true of “Essayism,” which comes broken into (mostly) brief sections, each purporting to excavate a particular line of reasoning. “On Lists,” “On Dispersal,” “On Anxiety” — the topics arise, one after the other, linked by citation or idea. “On the Fragment” leads to “On Aphorisms” to “On the Detail,” as if Dillon is exposing the line of his thinking, which is what the essay, if it’s working, does.

The essay, in other words, is not an answer but a question, a set of questions, a meander, a ramble, rather than an itinerary.

Essay writing is an art of digression, in which, Dillon observes, quoting Theodor Adorno, “[a]nyone wishing to express something is so carried away by it that he ceases to reflect on it.” We get distracted, in other words, by the act of saying from what we thought we had to say.

And yet, it’s also the case that every essay has a center, even if the essayist does not exactly know this when he or she begins. “An essay that performs its mode of attention,” Dillon puts it in a section titled “On Attention,” “… a framing of the act of attending to the world.”

For Dillon, that mode of attention, or attending, coalesces around the desire for consolation, which he raises five times in the course of the book. It’s the only theme (if we can call it that) to be repeated, and the intervals — 30 pages, give or take — are relatively uniform. This is not serendipitous but structural, as Dillon makes clear in the final “On Consolation” section.

“I could never write anything, for example,” he acknowledges, “without a thorough plan, as if these things — essays, articles, reviews, and even whole books — could and should be parsed like equations before they were brought into the world. But how else to write? How else to be?” Lest that sound contradictory — remember Adorno — it is also part of the point.

Planned or unplanned, the essay is an exploration, constantly creating its own shape. Hence, the reliance on short sections that move back and forth between reading and experience: Dillon’s battles with suicidal depression, his mother’s early death after suffering from same. “Is it possible to learn to be depressed to the point of feeling suicidal?” he wonders. “I think I had learned from my mother how to long for death.”

There is, he understands, no way to reckon with such a question. Instead, he digresses into a reflection on Roland Barthes’ final book “Camera Lucida,” an inquiry (essentially) into grief and image, “written directly out of the loss of his mother in 1977, and shadowed by the ‘mourning diary’ that he had begun to keep after her death.”

Is it any wonder this is one of Dillon’s touchstones? I don’t share his fascination with Barthes, or for that matter any of the theorists, but I am deeply committed to the self-exposure he uncovers in the work. Something similar might be said of “Essayism,” which also has roots in the death of its author’s mother, sublimating and expressing its bereavement at once.

This double vision, this built-in ambiguity or opposition, has everything to do with the paradox at the center of Dillon’s project, which involves “allowing your text, allowing yourself, to say many contradictory things at once.” The essay, in other words, is not an answer but a question, a set of questions, a meander, a ramble, rather than an itinerary. “[T]hese fragments I have written,” Dillon tells us, misremembering (or rewriting) T.S. Eliot, “in the sure knowledge that my ruin is coming, and this is all I’ve got.”

Where does this leave us? “Essayism” stands against the expectation that it leave us anywhere at all. Instead, Dillon argues, what matters is the investigation, the play of the essayist’s mind. “I think,” he writes, “that the essays I most admire are those that pay the minutest or most sustained attention to one thing, one time or place, one strain or strand of existence.”

That “Essayism” both does and doesn’t do this is part of its appeal. Late in the book, at the end of his discussion of “Camera Lucida,” Dillon turns from theory, in favor of “the strange air of searching and susceptibility” that infuses Barthes’ book. What he’s referring to is openness, which is the essayist’s most essential tool.

We write to get beneath the surface, we write to reveal ourselves. We do this especially when we do not know what we are revealing, when what the essay appears to be about becomes what it is really about, which is (or should be) a revelation to reader and writer alike.

Revelation? Yes, I think the word is appropriate; the essay is a form that requires us to write and read out of our vulnerability, after all. “It’s that vulnerability,” Dillon insists, in a line that also applies, I think, to his own book, “that I value in ‘Camera Lucida’ now … and in most or even all of the essayists I admire — no, love.”

David L. Ulin is the author of “Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles.” A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the former book editor and book critic of The Times

::

“Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction”

Brian Dillon

New York Review Books: 176 pp., $15.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.