Alexander Chee on Jonathan Lethem’s ‘A Gambler’s Anatomy’: ‘Oceans 11’ meets ‘Escape to Witch Mountain’ meets a meningioma

- Share via

I read the jacket copy for the new Jonathan Lethem novel a little surprised, a little uncertain — it sounded like “Escape to Witch Mountain” crossed with “Ocean’s Eleven”: A professional international backgammon player with telepathic powers has a concerning blot on his face that is distracting him as he plays a game in which he cannot be distracted.

We travel from Berlin to Singapore to Berkeley with one Alexander Bruno, tracing an unlikely path across the world in a novel that begins first as an international high-rolling gamblers’ intrigue and then becomes a love triangle, a confrontation with his past in the form of a former high school friend who goes from being his benefactor to his worst enemy.

The strangeness of the opening chapters carries for the whole novel, the latest from Lethem, known for “Motherless Brooklyn” and “The Fortress of Solitude.” Bruno arrives at the Berlin home of a German millionaire, one Herr Köhler, who has hired him for the night after a string of disappointing losses in Singapore. Like a reluctant and glamorous spy, Bruno flirts with a woman on the ferry there, even asking her for a kiss for luck after he loses a cuff link. As the games begin, and expensive Scotch is served, the host tries to impress Bruno with his knowledge of backgammon, and addresses what seems to be Lethem’s gambit. “An unprotected checker, sitting singly on a point, Köhler called a ‘blot.’ The term was universal in backgammon, and Bruno had heard it spoken by sheikhs and Panamanian capos de la droga, by men who didn’t know the English term for ‘thank you’…” After Bruno beats him for about 28,000 euros, he begins to feel regret. And then Bruno attempts to beam a thought to Köhler — “I tried to throw the game your way. The dice wouldn’t permit it. They don’t like you very much” — even though, he realizes, “there was no less likely candidate for susceptibility to Bruno’s old telepathic gift, which was anyhow abandoned.”

It isn’t his first try at telepathy in the novel, but at this point we have been told the strategies for backgammon are of the kind a good player can read — you need to be a board reader, not a mind reader, spying on your opponents’ cards, say, as in poker — to win at this game. And while Bruno is so bad at telepathy, such that he seems delusional for thinking he has the gift, the novel, meanwhile, ably delivers the pleasures of the game regularly, such that when the host begins to win, the result is even suspenseful. Enter a woman, masked and nude from the waist down, with a tray of shrimp sandwiches — a treat promised by his opponent. Bruno is overcome by a nosebleed then, and rushed to the hospital, where the truth of the blot comes clearer. As he checks out, he receives a voice message from the woman he flirted with on the boat, telling him that she was the masked sandwich server, and asking how he is.

In most novels about psychics, this is the sort of thing the telepath would be able to tell. But telepathy does not play the part we might imagine here. “A Gambler’s Anatomy” at first seems a part of a minority movement by American literary writers to embrace the psychic. From Heidi Julavits’ 2012 novel “The Vanishers” to Samantha Hunt’s 2016 novel “Mr. Splitfoot,” these books are not so much taking on the tropes of the psychic in science fiction (also a popular recent development) but moving the psychic into the realm of realist fiction. The telepathy here, though, is so consistently thwarted, it seems more like a fantasy of connection, a way to connect to anyone from within the nomadic life Bruno leads, as he goes wherever someone can afford to play against him, “a courtesan of sorts.”

His bad luck in Singapore would seem to be due to his high school friend, unlikely savior and bête noire, Keith Stolarsky, a wealthy real estate developer. In a scene that feels like pure William Gibson, they are reunited by fate in the Smoker’s Club, a secret VIP club in Singapore where Bruno’s fixer, Edgar Falk, has arranged for him to meet a high-ranking Singaporean official for a game; instead, here is his old high school friend, all insults and money. Soon, Stolarsky is anxious to challenge Bruno at backgammon and beat him, and the woman he is with, Tira Harpaz, is quickly the object of Bruno’s attention. The oldest game then plays out, a rivalry between the men, with Stolarsky anxious to humiliate Bruno by bettering him at backgammon, and Bruno trying the same, but with Harpaz.

The single unifying thread is how Bruno is like many Americans — he has no insurance and has ignored treating the blot for too long, and is now in grave danger. This is perhaps the strangest and most glamorous set-up for a meningioma tumor to be discovered and removed.When it becomes clear that Bruno must get surgery or die, Stolarsky offers to pay to fly him to the surgeon who can save him, and pays all his bills also — a deus ex machina of a kind, except that it comes with a price he must pay later. The gambling thriller becomes a medical thriller, then, and also a dream of one. The surgery results in a series of flashbacks into his past as a child with his mother, a part of a cult in Marin.

I imagine Lethem in a glamorous locale like the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, a Scotch in hand, saying, ‘I bet you I can make a novel about anything’

— Alexander Chee on ‘A Gambler’s Anatomy’

The medical nature of the novel is no less researched than the backgammon, and a series of increasingly harrowing descriptions of sinus and face tumors and the surgeries and treatments required to remove them reaches a kind of climax with a nine-hour surgery in San Francisco, in which the doctor is the central actor, and Bruno, only a figure laid bare as his face is destroyed in order to save him, emerging with a new one, just a cipher for the one taken from him.

Some of the novel’s best prose appears here:

“If the disassembled face could have somehow beheld what craned down into its core, the binocular microscope might have appeared as a pair of mad enlarged pupils, bled in every direction to the periphery, so as to make a sky of eyeball — a skyball.

“For hours, Behringer had borne down, into the paranasal and maxillary trenches, the nasopharynx, the orbital cavities, and into the tumor itself, the entrances he’d carved through its mass. His sense of scale was demolished. His tools and materials, the bipolar cautery and facial nerve stimulator, the tiny copper spoons and cup forceps and scissors, the neurosurgical Cottonoids, appeared like massive construction devices, excavators and steam shovels, brinked on shattered canyons of organ and tumor.”

Bruno awakens to find that the mask of the woman at Herr Köhler’s house seems to have become his, permanently, mirrored by the mesh underneath reconstructing his face after the surgery, horrifically visible in one scene when he is accidentally under a black light. By the novel’s end, he will have worn a series of masks until his identity has been obliterated. And the novel will have also. But this mirroring is intentional.

At times when I put the novel down, it felt like the result of a bet — I could imagine Lethem in a glamorous locale like one of those mentioned here, maybe the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, a Scotch in hand, saying, I bet you I can make a novel about anything to a mysterious figure hidden in shadow. But even when Bruno and his Berlin prostitute love interest are, near the end, in cars opposite each other, each making sure the other is alive before being separated, perhaps forever, this is a novel about desperate people living desperate lives as playthings to the rich, with Bruno seeing himself as no different from the half-naked woman serving the sandwiches.

Is it allegory? Is it genre? Is it literary or wanting to be literary? These were questions I kept asking as I read. In the end, I was reminded of the structure of the movie “Aliens,” where we see the heroine battle a monster that, we could easily forget as it rips through each of her friends and coworkers and the walls of the spaceship, has been kept alive by a company that hopes to use it to make weapons. Bruno is the blot, an unprotected point in the game, a game as hidden in some ways as the tumor in his face — a global economic system that makes gamblers and playthings of us all. In the end, it is a novel about the loneliness of life in a world made to serve only the richest, one that leaves the rest of us to make what deals we can to survive.

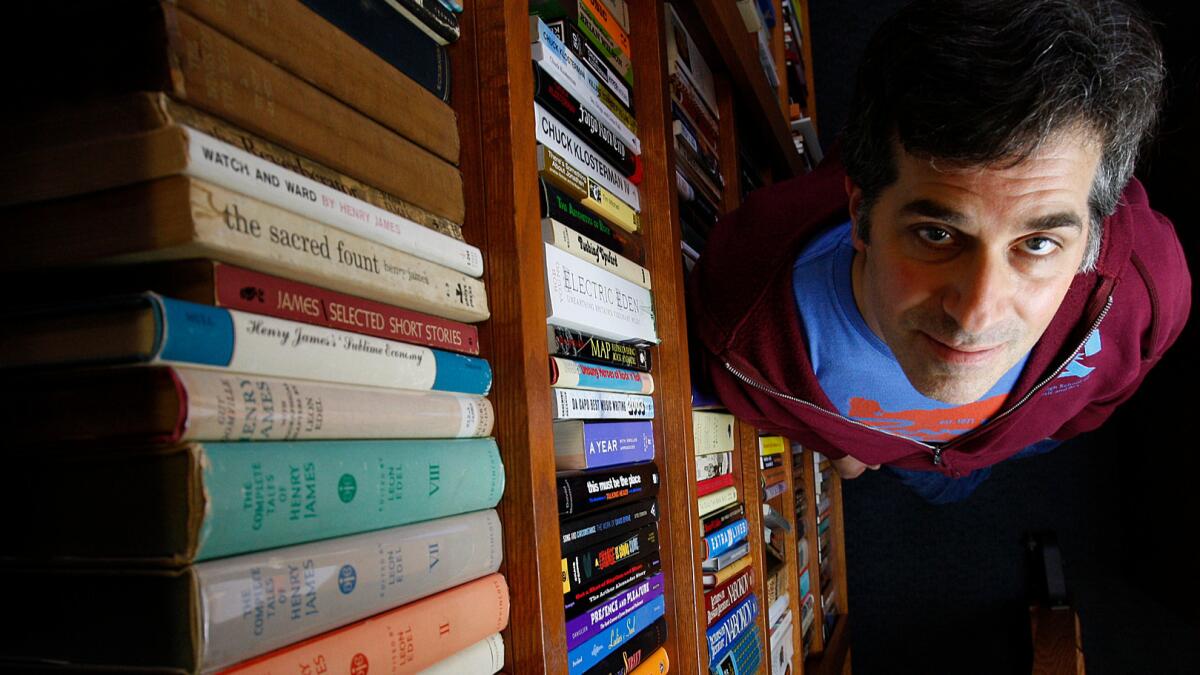

Chee is a critic at large for the Los Angeles Times, and is the author most recently of the novel “The Queen of the Night.”

Jonathan Lethem

Doubleday: 304 pp., $27.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.