A town and a mysterious a disappearance in Jon McGregor’s ‘The Reservoir Tapes’

- Share via

A girl goes missing. Police are questioning the parents.

“She’s only thirteen,” her dad says.

Or at least that’s what we think he says. The actual answers are omitted — questions are actually all we’re given in this tightly controlled and challenging chapter of blank spaces.

"I know she’s only thirteen, yes,” says a detective.

Then there’s a blank space.

“I wasn’t implying,” the official continues.

Then there’s another blank space.

It’s upsetting. By the end of this opening bit, you’ll wonder: What is happening? How worried should we be? Who are these people? Where is this girl?

*

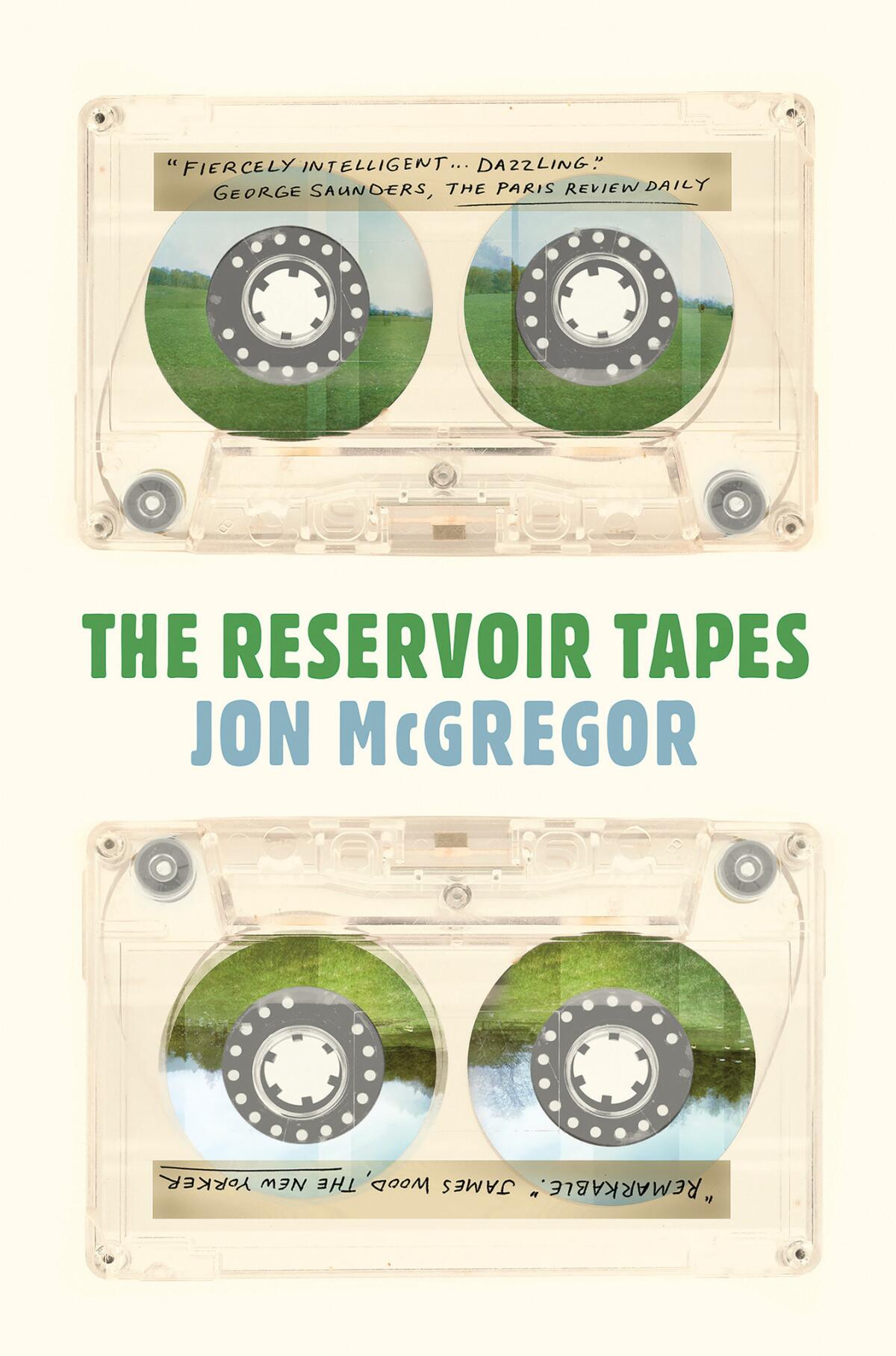

So begins an electrifying new novel, “The Reservoir Tapes,” by Jon McGregor, a slim volume in which each chapter takes place from the perspective of one resident of an unnamed town in the U.K. With this stylish and alarming book, the author is revisiting the same dense physical terrain and human territory as his previous novel, “Reservoir 13,” which was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize.

From the first chapter, we get this police perspective, the words dripping with judgment and precision. It’s the cold eye of the law, but the power of the “official account” is frustrating, this feeling that what transpires is never really full and complete.

The book’s second chapter veers away, into a lush, peculiar and more human scale, when we get to know Vicky, whose perspective on the loss of the girl is about how “people like to talk.” The third chapter allows McGregor to inhabit the mind of a young boy, Deepak, who is navigating as best he can his mother’s grief and his father’s indifference until the moment an old man lures him into an unfamiliar kitchen across town.

It’s scary stuff, this book, pounding as it does again and again with the insistent menace of people who go missing. But as the chapters accumulate, you begin to build a mental and emotional map of what’s left behind: a wounded town, fully specific enough to be engrossing but also slyly universal enough to make one consider their own common ground.

Ugliness and unease lurk behind pretty much every front door. An unstable woman, Ginny, also lost a girl — long ago, a different one, of course, her own, but who might look like this missing girl too. Ginny lost a husband too and, slowly, her mind. Another woman seems desperate enough, maybe, to seduce her best friend’s son. Across town, embroiled in a different mess, a third woman thinks she’s got it all figured out, working in a small town as a prostitute, but she isn’t ready for the day a man arrives with his son, and also a thick leather belt.

Handled with less inventive prose, a book like this might feel like a series of Stephen King-ish portraits of small people being horrible. But McGregor’s too inventive a writer not to dazzle and surprise, to create moments that confound and stir. In pages that recall some of our most excitingly dense and playful postmodern stylists, such as Padgett Powell and Robert Coover, it becomes clear, rather quickly, how dedicated to, among other pursuits, McGregor is to crafting first and final sentences.

*

Some vivid beginnings:

“The important thing to remember, Graham always said afterwards, was that no one actually died.”

“If he’d known the day was going to end with blood and fire, Liam would probably have got up earlier.”

“It wasn’t even a llama, for starters.”

*

Another of McGregor’s many talents is his stunning ability to render the landscape of the northern islands. “The mist started to clear, the sun burning suddenly through the last of it and the views opening up all around them,” he writes in one scene. “The flat heather moorland was featureless to the untrained eye, but in fact was teeming with detail: the bilberries and bog grasses, the mosses and moths and butterflies, the birds nesting in scoops and scrapes, the bog water shining in the late-afternoon sun. The warmth was rising from the ground already, the sky a rich blue above the reservoirs in the distance. A hundred yards away, a mountain hare broke from cover and thundered across the heather.”

Even if you can’t say for sure which one of the islands this is, sentences like that make you want to book a ticket.

*

But back to the missing girl: Her name is Becky, and perhaps it would be frustrating if it was true that we never learned exactly how or when she goes. But a kind of truth about Becky (and all of us) emerges. One day she’s in an apple orchard, daring an old lady to reprimand her for scaling the wall and stealing an apple. She and her parents fight, as all children and adults do. There might be a divorce. There might, in fact, be another installment of the Reservoir series.

Not all of us live in a small town, but our lives are equally divisible into characters, one of which looks just like us. What can you see in the dark?

Deuel is a writer in Los Angeles and author of the memoir "Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East."

::

Jon McGregor

Catapult: 176 pp., $22

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.