Review: Geoff Manaugh’s ‘A Burglar’s Guide to the City’ is a unique take on urban planning

- Share via

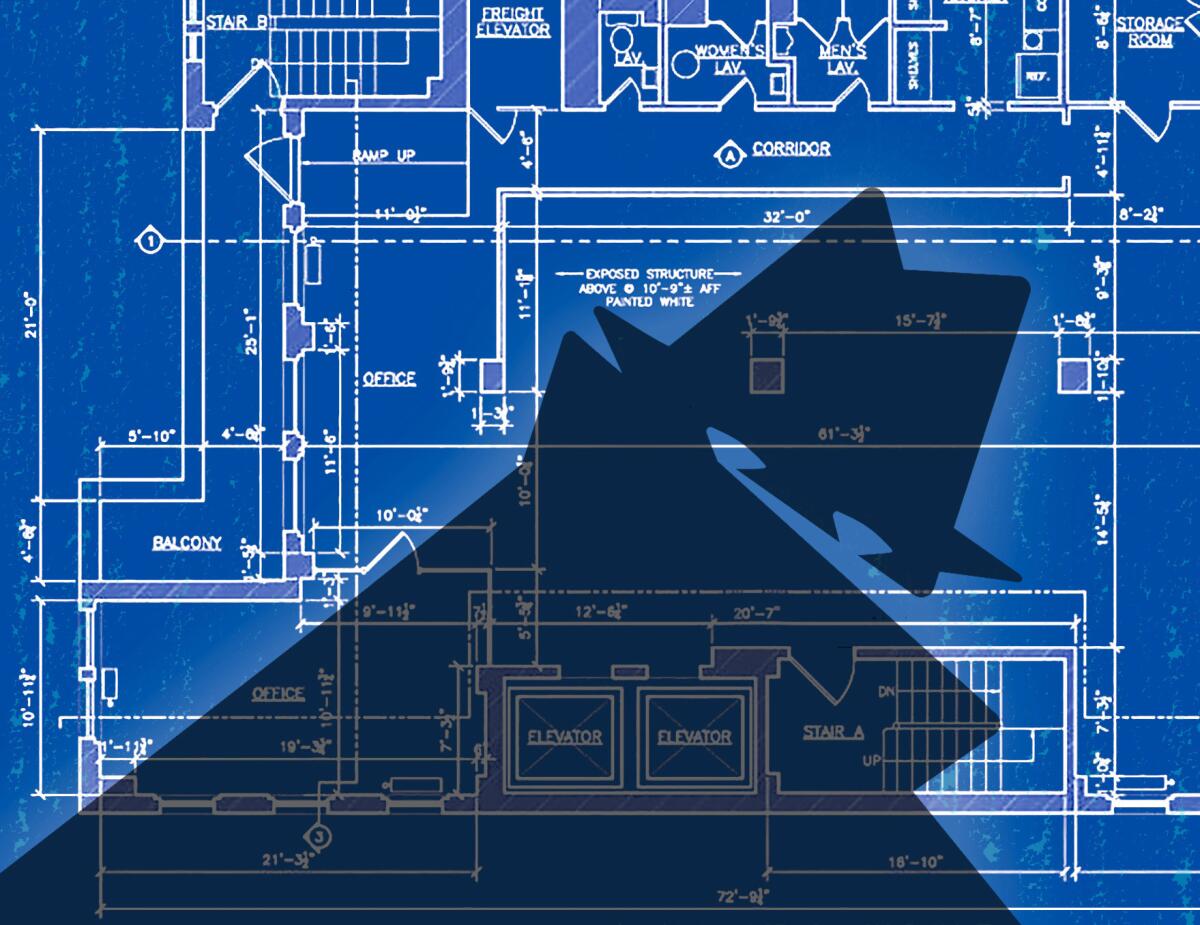

Despite its title, Geoff Manaugh’s “A Burglar’s Guide to the City” won’t teach you how to break into houses. It won’t help you outsmart wily cat burglars with ingenious home alarm systems, either. Instead, it explores something a lot weirder and more interesting: Manaugh argues that burglary is built into the fabric of cities and is an inevitable outgrowth of having architecture in the first place.

After years studying the odder side of architecture as a writer, university lecturer and founder of the popular BLDGBLOG website, Manaugh has found a way to explore urban planning in a way that is unique and slightly wicked.

He devotes the book to the “misusers” of cities, people who refuse to be stopped by walls, doors and ceilings in their quest to steal. Burglars are some of history’s greatest architecture critics, finding the flaws in every building — and rebuilding them from the inside, with tunnels under the floors of banks, or perfect portals through the drywall between apartments.

Manaugh describes buildings the way food critics conjure up the flavor of a sumptuous meal. There’s something delicious about his images of how burglars work their way inside buildings, moving through walls and floors “like worms, like serpents, as if shape-shifting back and forth between species, between minerals and plants, burrowing their way into buildings before disappearing again through the ceiling in ways that architects would never have imagined nor planned.”

“A Burglar’s Guide to the City” swerves between tales of criminals and the people who defend against them, introducing us to former detectives and present-day panic room designers. But undeniably the most fascinating parts of the book are the stories Manaugh has uncovered about criminal masterminds who exploited urban infrastructure and architectural quirks to get away with incredible heists.

We meet an anonymous Canadian burglar — now working in home security — who confesses to memorizing his city’s fire code to figure out the internal layouts of apartment buildings he robbed. Because every unit was required to have a fire escape outside, he could tell how many units were on a given floor. And he even knew which floors had mandatory unlocked fire exits, giving him a perfect way to enter undisturbed.

Another criminal, nicknamed Roofman, knocked over a series of McDonald’s across the U.S. by figuring out the franchise-regulated daily routines of workers. He knew exactly when people would be emptying cash registers and when the fewest workers would be around. He even knew what the typical layout of each restaurant would be, so he could easily drop into exactly the right place from his hidey hole in the ceiling. He is believed to have stolen from as many as 40 of the fast-food restaurants in nine states.

Eventually he was caught but almost immediately escaped from prison. After months of freedom, Roofman was caught for a second and final time. Officers discovered that he’d tunneled behind a bicycle display in a Toys R Us and from there into an abandoned Circuit City next door, where he built a secret apartment under stairs.

Characters like these reveal the often strange psychology of burglars, but they also underscore how burglary is knitted into the routines and regulations of cities. Of course, crime prevention is part of the urban landscape too. At one point, Manaugh introduces us to British law enforcement agents who have built a “burglar trap,” a fake house with obvious entries that is designed to lure burglars into the arms of local police, especially in high-crime neighborhoods.

As the book goes on, Manaugh gradually draws us into a vision of the urban landscape as something to be reverse-engineered, used against itself. Decorative structures on the outsides of buildings become handholds, and service stairwells become “architectural dark matter” to be explored for fun and profit. Even transit systems are hackable, as thieves plan their getaways with instruments that can give them the green lights they need to weave their way through congested city streets.

Though he clearly admires the way burglars turn cities inside out, Manaugh is careful to remind us that most of them are jerks who leave their victims feeling violated.

He spends weeks shadowing detectives, flying with police in helicopters over Los Angeles, asking them what architectural features would make it easier to fight crime. Mostly, their answers involve better ways to identify addresses from the air; they also wish for easier-to-navigate hallways in the warrens of public housing mega-structures.

Burglary is a peculiarly spatial crime, as Manaugh puts it. One cannot be a burglar without breaking into a structure, and the law goes to almost absurd lengths to define what these structures might be. Construction sites with no walls can be “broken into,” for example, even if they are completely open on all sides. Because “breaking and entering” is used as a sentence enhancement for other crimes like theft or rape, lawyers have invented arcane ways to define a built space, calling into existence what Manaugh calls “fictional architectures” made of nothing but legal webs.

The one shortcoming of “A Burglar’s Guide to the City” is its fragmented structure, full of tangents and digressions which add up to hundreds of vignettes but no sustained narrative. Manaugh offers us dollops of everything he researched, without a full meal. As a result, his trip to a museum of historical locks is given as much attention as the fascinating story of Roofman, and we’re left wanting more burglars and less noodling on the nature of lock-picking.

Still, the kaleidoscopic pattern of this book is its strength too. It’s not just a guide to crimes of the city; it’s a theory of cities, and the psychological contortions required to live in tiny boxes right alongside each other, with only thin, easily broken walls between us. You’ll never look at your home the same way again.

::

“A Burglar’s Guide to the City”

Geoff Manaugh

FSG Originals: 304 pp., $16 paper

Newitz is the tech culture editor at Ars Technica and author of “Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction.” Her first novel, “Autonomous,” will be published by Tor in 2017.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.