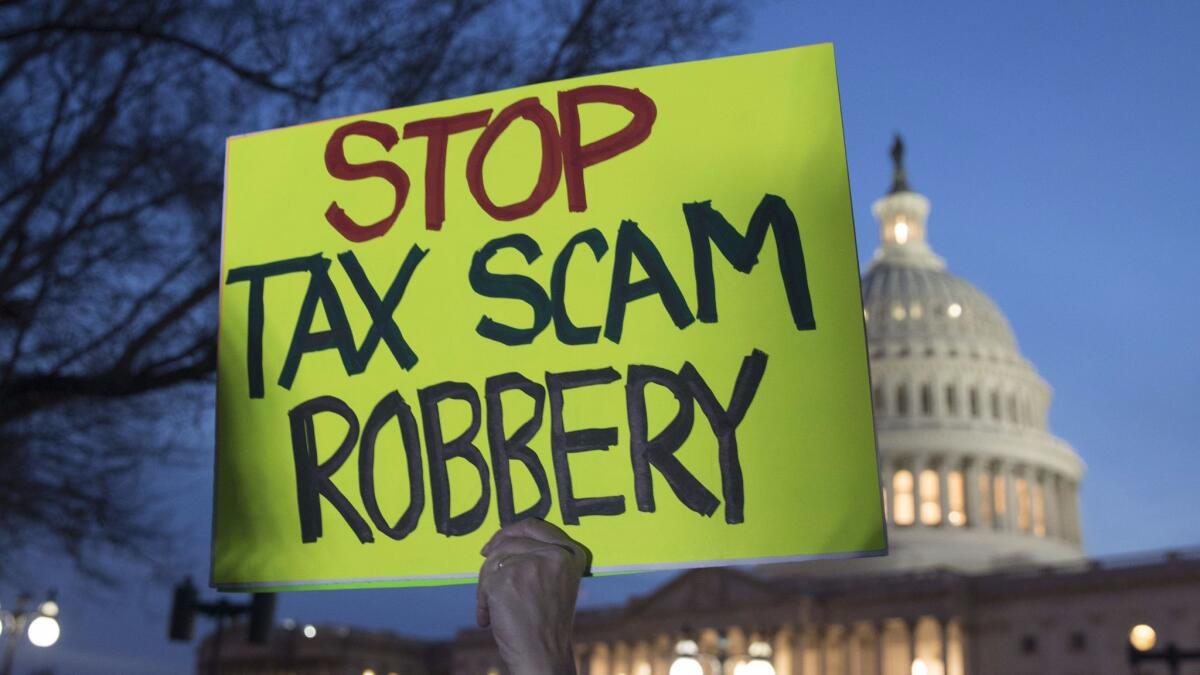

Killing the state and local tax deduction may be unconstitutional. Here’s why

- Share via

The debate over eliminating the federal tax deduction for state and local taxes — a linchpin of the Republican tax cut plans now working their way through Congress — has focused on the economic and political effects of the change. But that may be the wrong discussion. The question is whether eliminating the deduction is even constitutional. History suggests that it’s not.

The most cogent analysis of this issue comes to us from the grave — specifically, from the late Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.). Moynihan addressed the issue in a 1985 speech, later published in the political science journal Publius.

Leaders of states that rely on state and local income taxes for a large share of their revenue, including California, have threatened to bring a legal challenge to a tax bill that eliminates the deduction. They would do well to take their lead from Moynihan.

There are arenas of government that must not be invaded by other governments.

— The late Sen. Daniel P. Moynihan, 1985

At the time of his speech, the state and local tax deduction was under attack by the Reagan administration, which like today’s GOP, was looking for ways to pay for a tax cut for the rich. Moynihan labeled the idea “a profound constitutional error.”

Moynihan drew his argument from the principle of federalism enshrined in the Constitution, the essence of which is that “there are arenas of government that must not be invaded by other governments.” He observed that the notion that this applied to taxation had been understood dating back to the origins of the federal income tax, enacted under Abraham Lincoln to finance the Civil War.

The Revenue Act of 1862, Moynihan noted, provided that federal tax liability was to be calculated only after state and local taxes were first deducted, “and this under the most pressing emergency conditions ever faced by our country.” The deduction was enshrined in the Revenue Act of 1913, which created the modern federal income tax.

A few contemporary commentators have noticed that eliminating the SALT deduction, as it’s known today, invades local prerogatives. Progressive pundit John Stoehr wrote recently that the change would be “a violation of the states’ rights the Republicans say they alone represent.” At the other end of the ideological spectrum is Stan Veuger, a fellow of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, who called the deduction “a linchpin of the federalist system,” which “expresses our preference for local solutions to local problems.”

But that’s definitely a minority approach. Virtually the entire debate over the current tax cut bills has treated the SALT deduction as just another loophole, akin to the mortgage interest deduction, that favors the wealthy. The political component of the discussion relies on the fact that the states with the highest percentage of residents claiming the deduction — such as California, New York, New Jersey and Maryland — tend to vote Democratic. In our denatured political discourse, the idea that Republicans in Congress would turn their gun sights on Democratic states is seen as sort of adorable.

It’s also commonly argued that, insofar as the deduction is most heavily concentrated in big, urban states, it’s tantamount to a “subsidy” of blue states by their poorer red neighbors.

Moynihan, a New York Democrat, albeit one who wasn’t averse to taking a conservative stance on issues from time to time, had little regard for these arguments. He thought it inaccurate to label the deduction a “tax expenditure” — a term used to describe giveaways to favored groups through the tax code. “I do not think we should let the Treasury Department get away with calling it a federal ‘subsidy,’ ” he added. “In diplomacy, this is known as semantic infiltration: if the other fellow can get you to use his words, he wins.”

In any event, the notion that other states “subsidize” big blue states through the SALT deduction happens to be wrong. As New York State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli demonstrated in a 2016 study, the “subsidy” generally goes in the other direction: The states with the largest state and local tax burdens typically paid out more to the federal coffers than they received in return. The states with the biggest outflow were those on the West Coast and Northeast, and those receiving the largest inflows tended to be Southern states with low state and local taxes.

Another principle Moynihan discussed was the issue of “double taxation.” Interestingly, an aversion to “double taxation” is frequently cited by Republicans and conservatives to justify reducing or eliminating taxes on dividends — dividends already are taxed once as corporate income, so why should they be taxed again when they’re received by shareholders.

But eliminating the SALT deduction would be a more far-reaching example of double taxation, Moynihan said, citing a resolution by the National League of Cities calling the deduction “a fundamental statement of the historical right of state and local governments to raise revenues and of individuals not to be double taxed.” As it happens, the Supreme Court has spoken on the issue of double-taxation: It’s wrong. In a 2015 decision written by Justice Samuel Alito, the court ruled that a Maryland provision denying its taxpayers credit for taxes paid to other states was unconstitutional. Expect the states’ challenges to the GOP tax bill to cite that ruling (Comptroller vs. Wynne) prominently.

In 1862, Moynihan noted, Rep. Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont, then chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, warned that eliminating the SALT deduction would “perplex and jostle, if … not actually crush, some of the most loyal States of the Union.” Moynihan called it a “huge and final irony” that eliminating the deduction would transfer more resources to the federal government, allowing it to grow larger — exactly the outcome that the advocates of “small government” in the Republican congressional caucus say they don’t want.

Moynihan and his colleagues managed to defeat the Reagan administration’s effort to eliminate the SALT deduction. Subsequent efforts also failed. At this moment, the GOP plan to take an ax to the SALT deduction looks like a juggernaut. But history and the Constitution may say otherwise.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.