Are most academic papers really worthless? Don’t trust this worthless statistic

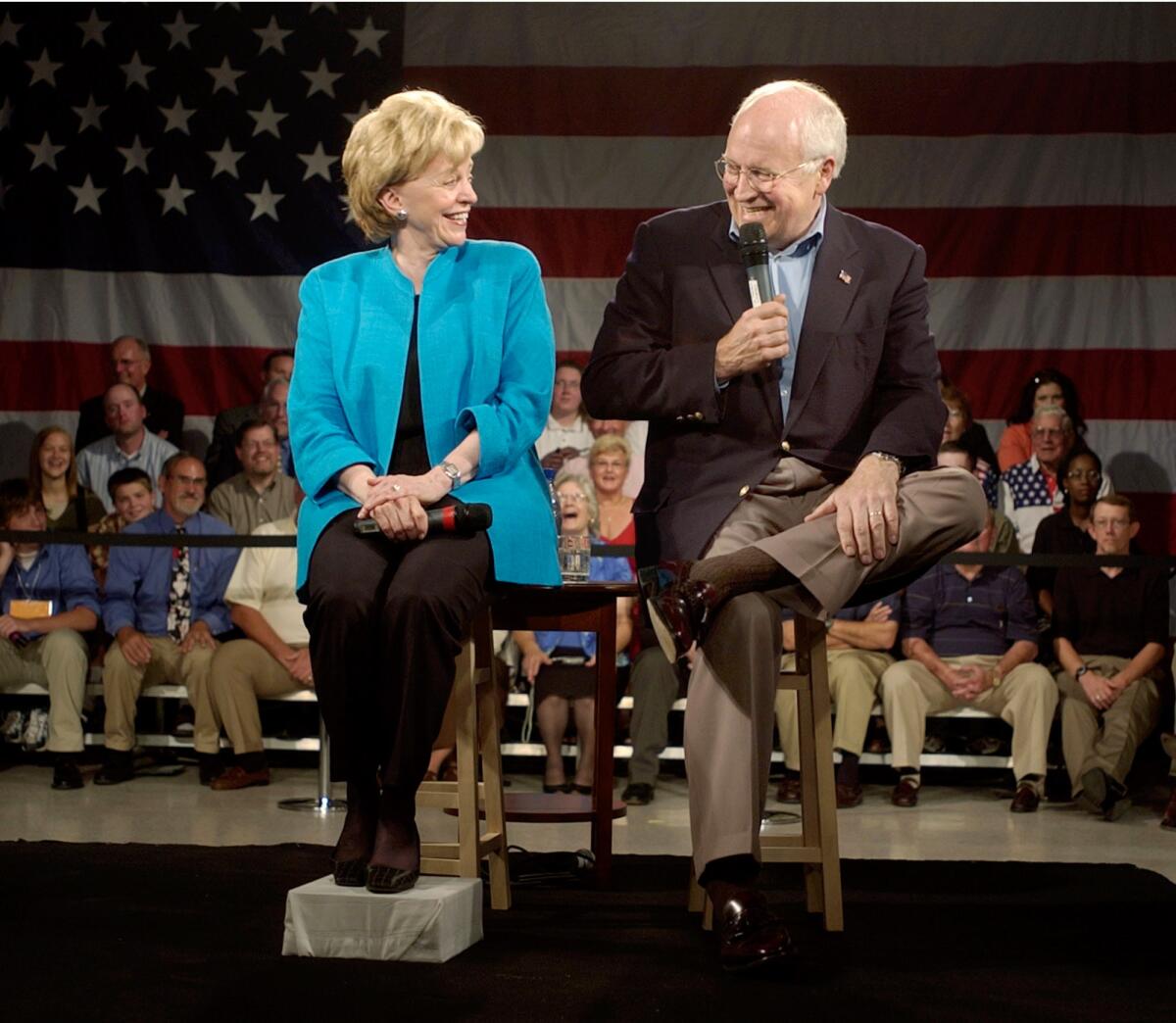

Lynne Cheney, left, with her husband the then-Vice President in 2004. Did she lead an ex-Harvard president astray with a 1991 speech?

- Share via

One of the most eye-catching statistics published during the slow-news period of Thanksgiving week was about academic research.

The finding was that the vast majority of articles published in the arts, humanities and social sciences are never cited by another researcher. The implication, of course, is that they go almost entirely unread, and that therefore the research is largely worthless. Some 98% of articles in the arts and humanities and 75% in the social sciences are never cited. Things are not much better in the hard sciences--there, 25% of articles are never cited and the average number of cites even of those is one or two.

If statistics seem so mind-blowing they can’t possible be true? They’re probably not!

— Yoni Appelbaum of The Atlantic

For critics of modern academia, these shocking numbers have the virtue of validating some cherished presumptions, including that university professors are a lazy bunch turning out mediocre or useless research just to fatten up their resumes in a publish-or-perish world.

But before we go crowing about these findings and congratulating ourselves for our instincts, we should ask if they’re true.

They’re not.

In fact, they’re about 30 years old. The conclusions drawn from them were challenged almost from the outset by the original studies’ publishers. And those conclusions were based on a misreading of the original studies anyway.

“If statistics seem so mind-blowing they can’t possible be true ... they’re probably not!” observes Yoni Appelbaum of The Atlantic, who caught the shortcomings of the data almost immediately and outlined them last week in a series of tweets.

The exploitation of old and misinterpreted data for an analysis of modern university research is a good illustration of how information gets disseminated in today’s world of social media. That’s especially interesting, since the original studies aimed to analyze how knowledge is disseminated.

So let’s give this affair a closer look.

The citation that got all the attention Thanksgiving week came from Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein, in a column offering four options for universities to “rein in costs”--such as offering classes year-round, capping administrative costs and exploiting new technologies. Pearlstein’s piece is worth reading for its insights into public concerns about university costs, though one might find it useful to read it in tandem with this cogent critique, also in the Post, by Daniel Drezner of Tufts.

One of Pearlstein’s prescriptions is that universities should offer “more teaching, less (mediocre) research.” Labeling any research as “mediocre” is a subjective generalization, as is Pearlstein’s blanket assertion about research by tenure-seeking faculty that “much...has little intellectual or social impact.” But he bolsters these assertions with the empirical “uncitation” data above.

Pearlstein’s source for the numbers is a book by former Harvard President Derek Bok, “Higher Education in America” (2013, revised 2015). That certainly gives the data a glowing pedigree, especially because Bok characterized the statistics as “impressive,” even “staggering.”

Unfortunately, however, Bok didn’t display much care in assembling or using these numbers before publishing them. His chief source for them, according to his footnotes, was a 1991 speech by Lynne Cheney, then the chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

But Cheney is hardly an objective source; the wife of former Vice President Dick Cheney, she was viewed during her tenure at NEH as an ideological warrior hostile to research that strayed from the orthodox Western cultural canon. She used the “citedness” figures to validate her view that academics were devoting themselves to “foolish and insignificant” topics, which happened to coincide with topics of which she personally disapproved. She appeared to be dressing up an ideological viewpoint with what seemed to be empirical data.

Bok’s secondary source was a 1991 article by David P. Hamilton of Science magazine, the second of two Hamilton published on the data. But Hamilton’s analysis had been directly challenged by David A. Pendlebury of the Institute for Scientific Information, which had published the original studies. Pearlstein told me he drew the data from Bok’s book and wasn’t aware of the old controversy.

Pendlebury pointed out in a letter to Science that the ISI studies encompassed much more than papers in academic journals, but also “meeting abstracts, editorials, obituaries, letters like this one, and other marginalia, which one might expect to be largely un-cited.” (Emphasis in the original.)

He added that such material tended to be much more prevalent in the humanities and social sciences than the hard sciences--three times more so in the humanities than the hard sciences. Moreover, Pendlebury objected, the data told us nothing about academic “performance.”

It might be interesting, he said, if the numbers showed any trend toward more “uncitedness.” But they didn’t, except in the social sciences, where there was a decrease in uncited papers from 1981 to 1985.

So here’s the bottom line: Data from a study performed three decades ago and never updated were used to make assertions about academia in 2015. The data did not show what they claimed to show. An erroneous analysis offered at the time of its publication was debunked almost instantly; but somehow the debunking got forgotten while the data lived on, well past their sell-by date. And then the numbers got picked up by an old-media newspaper and shot around the globe via new-style social media. They looked true, but on almost every level that mattered, they were useless.

What does that tell us about academia? Nothing. But this superb illustration of Stephen Colbert’s “truthiness” is a reminder of the necessity of validating even seemingly unassailable data by checking the original source. Readers today are both overinformed and underknowledged (or maybe vice versa), because facile narratives can be constructed from seemingly concrete statistics that don’t mean anything at all.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.