While UnitedHealth pulls the plug on Obamacare, data shows where and why it failed

- Share via

UnitedHealth Group, the nation's largest commercial health insurer, made good on a six-month-old threat and announced Tuesday that it will pull out of Affordable Care Act exchanges in all but "a handful of states" after this year. The questions that raises, as we observed a couple of weeks ago, are will that hurt, and if so, who does it hurt?

United had previously announced its withdrawal from Arkansas, Michigan, and Georgia (although a subsidiary, Harken, will continue to serve some Georgia counties). Other early reports said the company would leave Oklahoma and Louisiana. United has filed a rate request for 2017 in Virginia, albeit for HMOs only, so it appears to be staying in that state at least for one more year.

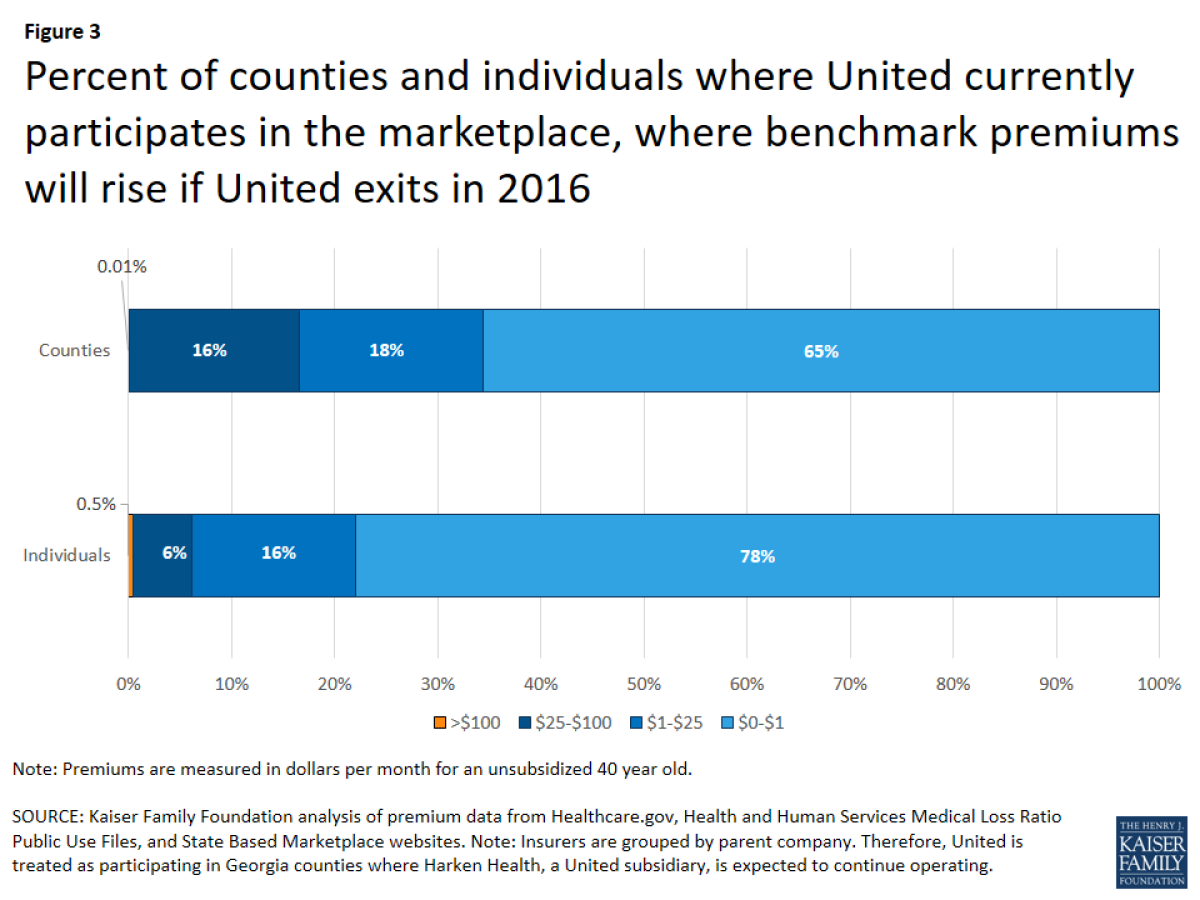

As it happens, new data released by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Dept. of Health and Human Services show that because of the big company's tentative entry into Obamacare's individual exchanges in the first place, the impact of its withdrawal will be little noticed nationwide, though it could drive up premiums in some rural areas.

United does not generally offer low premium plans in the Marketplaces....As a result, the effect of a United withdrawal nationally would be modest.

— --Kaiser Family Foundation

Kaiser analysts Cynthia Cox and Ashley Semanskee observe that United was a cautious entrant into the Obamacare exchanges, stepping gingerly into the water in only a few states in 2014, and expanding during the following two years. In general it was never a low-premium insurer, which limited its customer base; company executives said Tuesday that United is serving about 795,000 exchange enrollees out of the total of about 11 million.

"United does not generally offer low premium plans in the Marketplaces," Cox and Semanskee report. The company offers the lowest or second-lowest silver plan in about one third of the counties where it participates in 2016. As a result, the effect of a United withdrawal nationally would be modest...The national weighted average benchmark silver plan would have been roughly 1% higher in 2016 had United not participated (less than $4 per month for an unsubsidized 40-year-old)."

HHS supplemented Kaiser's findings with results from healthcare.gov, the website for enrollment on federally-run exchanges. United policies were not priced competitively in any of the five most-populous states where exchange enrollments go through the federal website--Florida, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Georgia. More than 90% of the populations of all five lived in areas where they could find a silver plan cheaper than United's, an agency spokesman said.

United's withdrawal will hurt in some regions, Kaiser found, particularly counties where competition was already scarce, and United's departure will leave only one or two insurers offering individual plans. These tend to be rural and sparsely populated. If united were to exit from all states, Kaiser reckoned, the number of counties with three or more competing insurers would shrink from 64% of the total to 48%, though the proportion of the population served by three or more insurers would fall from 85% only to 70%.That's an indication that other major insurers, including Aetna, Anthem, and independent Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, are still competing vigorously in the most densely-populated portions of the country.

These figures still leave open the question of why UnitedHealth's experience with the exchanges was so unhappy. It's proper to remember that although it's the nation's largest commercial health insurer, United operates chiefly in the employer-sponsored, Medicare, and Medicaid markets. These are more predictable in terms of both risk and revenue than the ACA market, which was radically new when it was launched in 2014. Until then, individual insurance was a cherry-picker's game entirely under the control of insurers, who shunned customers who appeared to be medical risks and larded their customer base with the young and healthy.

The Affordable Care Act outlawed such "medical underwriting." Insurance companies had to learn the risk profile of the Obamacare customer base, and therefore the proper price to charge, on-the-job. This is still a work in progress after only three years. Aetna, Anthem, Humana, and several Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans have reported losses on the exchanges, but have expressed more confidence than United that they'll eventually figure out the market and make money.

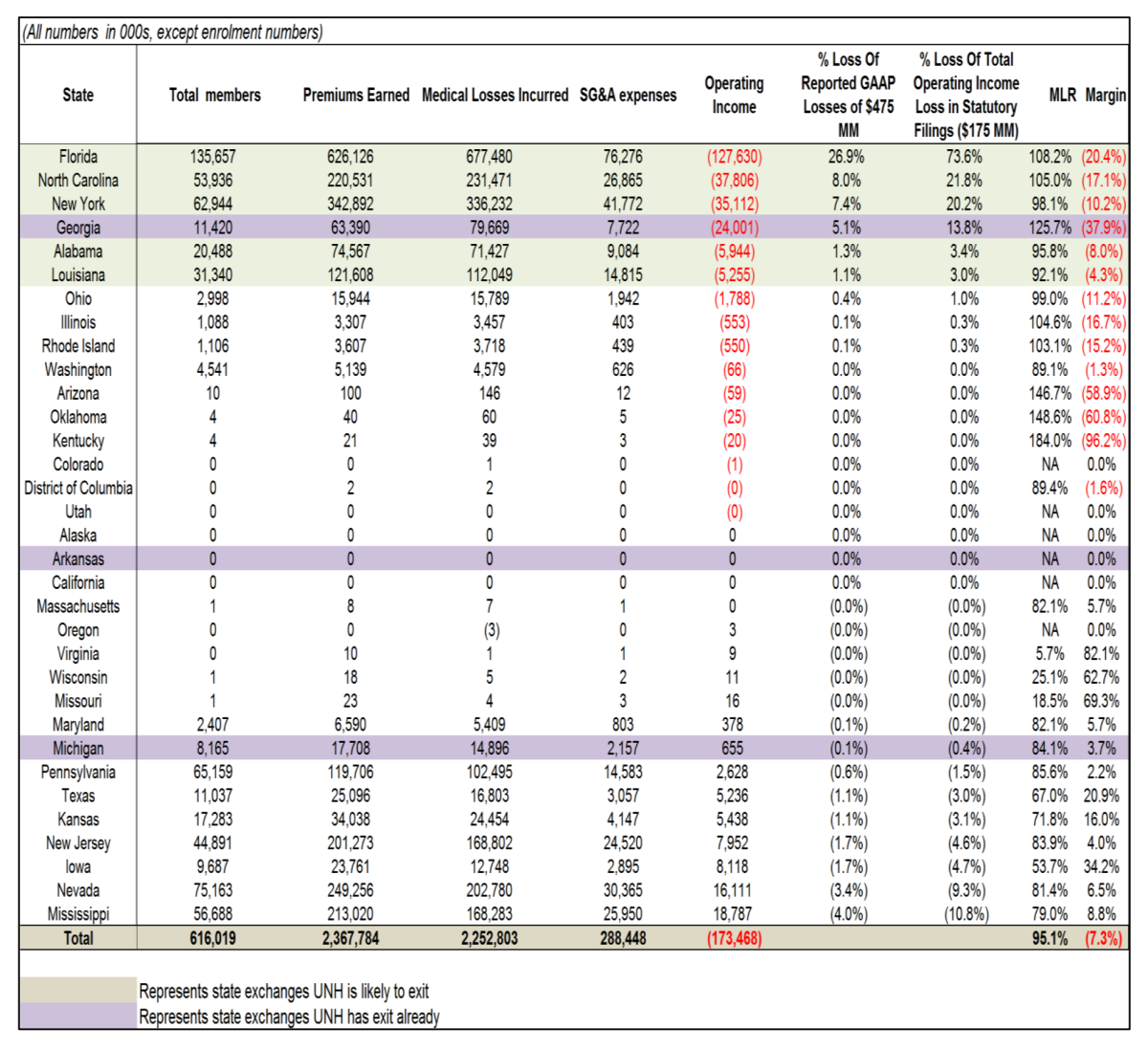

A survey by the investment bank Leerink Partners (see above) indicates the nature of United's miscalculation. Drawn from 2015 financial disclosures, the data show that Florida alone--the company's biggest Obamacare state, with 135,657 enrollees last year--accounted for nearly 27% of the company's reported $475 million in losses on the exchanges. Georgia was another red-ink state, with 11,420 enrollees and 5% of the loss. In at least one state where the company has announced a departure, Michigan, United seemed to have made money last year. But its departure may be related to its doubts that regulators will approve enough of a rate increase to make the business worthwhile.

Leerink analyst Ana Gupte believes that losses will continue on the exchanges for some time, though insurers will be bailed out, to a certain extent and temporarily, by the deferral for 2017 of a $13.9-billion health insurers excise tax. She also believes that United's problems with Obamacare will prompt federal regulators to look more kindly on the proposed mergers of Aetna with Humana and Anthem with Cigna, which have been rationalized in part as attempts to bulk up to better manage ACA costs. Whether the creation of these mega-insurers really will serve the public by delivering better and more stable healthcare is an open question. The only known outcome is that the entire healthcare landscape is undergoing massive change.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.