‘Flash Boys’ IEX stock exchange opens. Its goal: Rein in high-frequency traders

- Share via

At mutual fund giant Capital Group, investment managers study stocks, looking to buy when they’re underpriced and sell when they’re overpriced. That’s how the downtown L.A. firm has made healthy returns for its millions of investors since the 1930s.

But over the last few years, Capital Group has been looking toward something else to help boost its returns: a new stock exchange founded by a group of Wall Street evangelists, lauded in a bestselling book and powered by a spool of 38 miles of fiber-optic cable tucked away in a New Jersey data center.

That new exchange, the Investors Exchange or IEX, the subject of Michael Lewis’ 2014 book “Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt,” was founded on the premise that ordinary investors — particularly the middle-class ones whose money is managed by big firms like Capital Group — need protection from high-speed trading firms that manipulate the market.

Michael Lewis’ ‘Flash Boys’ focuses on Wall Street computer scheme »

After a nearly yearlong struggle for approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission, IEX today becomes a public stock exchange, like the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq, marking a victory for both the upstart exchange’s founders and Capital Group.

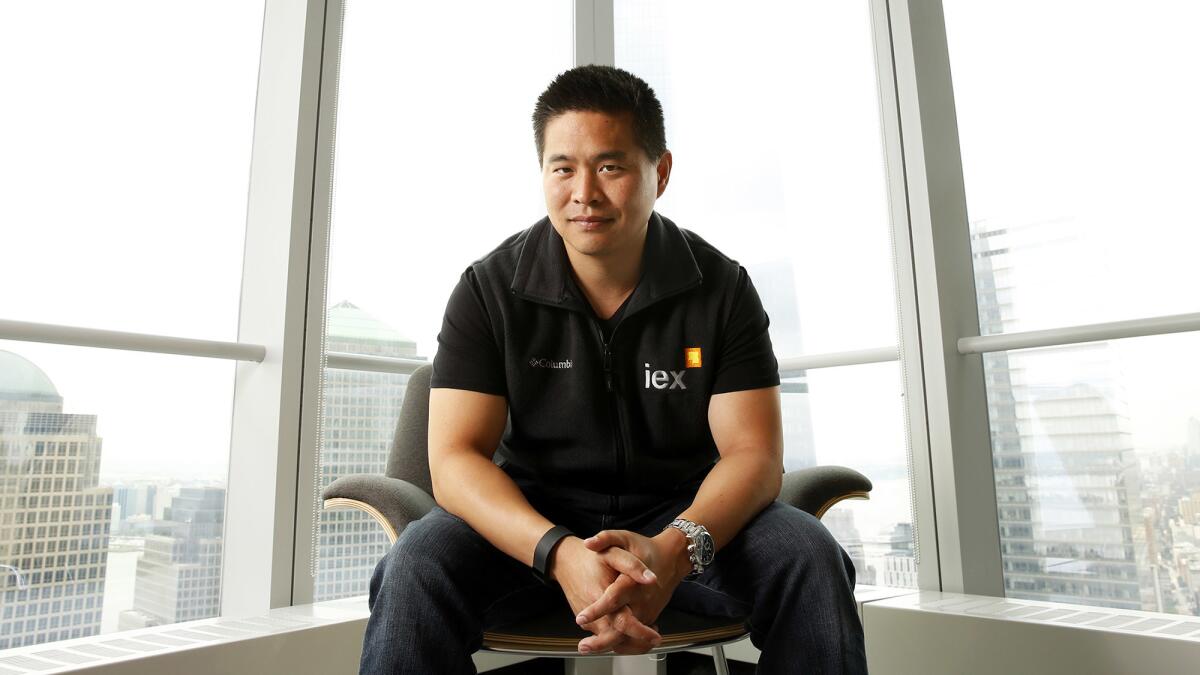

The L.A. investment giant was the first firm that agreed to back IEX, support that exchange founder Brad Katsuyama said was crucial to lining up other early investors.

“From the very beginning, they stood behind us,” Katsuyama said. “They were at one point our only committed investor. Without being able to use them to get other investors to come in, I don’t know where we’d be.”

Matt Lyons, Capital Group’s global trading manager, said it’s satisfying not only to see IEX make it this far but also to know that the problems that led to Capital Group’s investment have been brought to wider attention.

“Our commitment to IEX was a way for the Capital Group to express our belief that there was a real need for alternatives to the current market structure,” Lyons said.

Unlike other exchanges, IEX intentionally slows down trading, requiring all trades to go past what the firm calls a speed bump — hardware that adds a tiny delay just long enough to stymie some of the strategies the exchange’s founders say high-speed traders use to prey on big investors like Capital Group.

The new exchange says that levels the playing field between long-term holders of stock like Capital Group and the high-frequency traders that make money by rapidly trading shares and making tiny profits on each trade.

In an age of near-instant trading, that notion has rankled some traders and exchange operators who argued that the SEC would be creating a more complicated market, and not necessarily a fairer one, if it approved IEX.

The SEC disagreed and signed off on the application in June, clearing the way for IEX to become the nation’s 13th public exchange.

Since 2013, IEX has operated as a private exchange and, on the typical day, handles about 1.5% of total U.S. stock trades. As a public exchange, it will be able to host initial public offerings and handle more trading volume.

The fierceness of the opposition to IEX is thanks in part to the almost evangelical tone Katsuyama and his co-founders have taken in describing what they see as a rigged stock market, in which established exchanges have created advantages for some investors at the expense of others by selling faster access to their data feeds.

The debate has had an unusually high profile thanks to Lewis’ “Flash Boys,” which delved deep into the vagaries of the stock market, painting Katsuyama and his IEX co-founders as heroes while casting much of the rest of Wall Street — not just high-speed traders — as villains.

Lewis declined an interview request because he is on deadline for another book project.

Still, Katsuyama said “Flash Boys” has been a huge positive for IEX, bringing public attention to the exchange and creating an outcry over Wall Street practices that otherwise probably wouldn’t have materialized.

“Without that, the opposition would have been just as fierce, but it would have been done privately and without public attention,” he said.

Perhaps more important than the book, though, were Capital Group and other investment firms that backed IEX early on — well before “Flash Boys” — and gave Katsuyama and his team the capital they needed.

Katsuyama said he ran the idea of creating a new stock exchange by Capital Group in 2011. The next year, the L.A. firm took the lead with a handful of other big institutional investors, including hedge fund Pershing Square Capital, in a $9.4-million funding round.

Capital Group has not disclosed how much it invested, though Lyons said the firm owns less than 5% of IEX. The exchange went on to raise millions more from venture capital and private equity firms and from casino magnate Steve Wynn.

Lyons said he and others at Capital Group knew Katsuyama from his days as a trader at Royal Bank of Canada, and they both trusted him and thought his ideas would address at least some of the problems they saw in the market.

But he said Capital Group’s investment in IEX was about more than that.

“We felt it was important, if not to solve the problem, to at least let our investors know Capital Group was concerned about what was happening,” Lyons said.

Capital Group is a massive firm, managing nearly $1.4 trillion in assets for tens of millions of investors. The bulk of its business is mutual funds, the type of investments that form the backbone of many Americans’ retirement savings.

With that much to invest, when Lyons buys and sells stock for the firm, he’s often looking to buy or sell hundreds of thousands, even millions, of shares — something that comes with risks not shared by the casual investor.

The trick for Capital Group is to make those huge moves without tipping off the rest of the market. Let everyone know there are 1 million shares for sale and the price could fall. Let everyone know you’re looking to buy and prices would climb.

“If you demand more than the available supply, you’re going to change the price,” Lyons said. “Traders try not to tip off the market that there’s a large demand for these securities. They try to hide our intent in the marketplace.”

But starting nearly a decade ago, amid the rise of electronic trading, Lyons said it seemed like other traders knew what Capital Group was up to whenever it made big trades, with stocks suddenly changing price just as the firm moved to buy or sell.

“We saw movement in stocks that was unexplained other than by there being someone out there who understood what we were trying to accomplish,” he said. “People anticipated what we were doing.”

When Katsuyama was at RBC, one of the firms that executed stock trades on Capital Group’s behalf, he noticed the same thing. He’d place an order for Capital Group or another big investor and see the price suddenly shift.

Those people, Katsuyama said, weren’t people at all but computers. And they weren’t anticipating Capital Group’s moves but outrunning them.

Here’s what was happening: Say Katsuyama was looking to buy 10,000 shares of a particular stock for Capital Group. He might see 10,000 shares for sale, but those shares would be listed on any number of stock exchanges.

To get those 10,000 shares, Katsuyama would have to send electronic trading orders to several exchanges, with each order arriving at a slightly different time.

See the most-read stories in Business this hour »

A signal might have to travel through 10 miles of underground cable to reach one exchange and 30 miles to reach another. The fractions of a second difference it takes for an electronic signal to travel that extra 20 miles turns out to be a big deal.

Katsuyama said high-speed trading firms — using computers hooked directly into the stock exchanges — could see that someone had bought up all the available shares on the first exchange, then quickly snap up shares on other exchanges. It’s what Lyons and others call “information leakage.”

“They’re racing us to those exchanges, buying stock ahead of us and then attempting to sell it to us at a higher price,” Katsuyama said.

Speedy investors can get the upper hand on slower traders in other ways too, he said, including by taking advantage of tiny differences in prices between exchanges — differences that last for just fractions of a second.

All of this has a few effects on the market. For one, it means that Capital Group and other big firms might not get the best possible price when buying or selling stock, cutting into returns.

Though Lyons can’t put a dollar figure on those reduced returns, he said a trading system that doesn’t telegraph Capital Group’s intentions should benefit investors through fairer pricing.

“It’s leveling the playing field,” Lyons said. “There’s no advantage based on how quickly you can get to one place versus someone else.”

In a letter urging the SEC to approve IEX as a full exchange, the Teacher Retirement System of Texas, a pension fund that manages more than $125 billion, suggested that trading through IEX could save the system millions of dollars a year.

IEX slows down all of the trades that go through its system with a 38-mile coil of fiber-optic cable that sits between the outside world and the exchange’s main computer.

It takes trading signals 350 millionths of a second to get through the coil. That’s a tiny delay — it takes hundreds of times longer to blink — but it’s enough to take away the advantage of speedier traders.

Jatin Suryawanshi, an IEX board member and head of global quantitative strategy at stock brokerage and investment bank Jefferies, said the additional time allows an investor’s order to be executed on IEX before high-speed traders can start racing that order to other exchanges.

“The client’s order comes in, IEX holds the execution by 350 microseconds, then executes the order, then holds the trade report by another 350 microseconds,” he said. “It’s giving the client a cushion and protection.”

But the NYSE and other IEX critics have argued that the delay could hurt rather than help investors. In letters to the SEC objecting to IEX’s application to become an exchange, NYSE officials said allowing an exchange to intentionally slow down trading could lead to investors getting stale information or, perhaps worse, could make the stock market more complicated.

“We believe that allowing exchanges to intentionally delay access to the protected quotations is not in the interests of investors,” NYSE Group General Counsel Elizabeth King wrote in April.

She went on to argue that allowing exchanges to institute even tiny delays would be “a deliberate step towards even more market-wide complexity and fragmentation” and would “open up a new dimension on which exchanges will compete.”

Indeed, following the SEC’s approval of IEX’s application, executives from both the NYSE and Nasdaq have said they are considering speed bumps of their own.

Bill Hart, chief executive of Modern Markets Initiative, a trade group created by high-frequency trading firms, said there’s little hard data to suggest that the predatory practices outlined by IEX and by “Flash Boys” even exist.

He pointed to a recent study by professors at UC Berkeley that found little evidence traders could make money using one of the high-speed strategies outlined in “Flash Boys.”

The study looked at whether traders could use the time it takes for price information to travel from one exchange to others in order to trade ahead of slower investors.

“In the current market, you can’t make money on that specific strategy,” said Justin McCrary, one of the study’s authors, though he noted that there could be other strategies high-frequency traders could use.

Katsuyama takes issue with the study’s findings and said that if there weren’t problems in the market, investors wouldn’t continue to back IEX.

“Data can tell any story you want it to when the market is as complicated as it is,” he said. “If this were all fiction, we would have failed on our own merits, or lack of merits. But that’s not the story that’s playing out.”

He noted that IEX continues to have the support from a bevy of big backers amid opposition from other exchanges and some — though not all — high-speed trading firms.

Many institutional investors and Wall Street firms wrote letters urging the SEC to approve the new exchange. That includes the California State Teachers’ Retirement System and public pension systems in Missouri, Texas and New York, as well as investment bank Goldman Sachs.

“For people to understand what we’re trying to accomplish, look at the firms who were actively trying to oppose us. It was the exchanges who sell speed and a select group of high-speed traders who use that to their advantage,” Katsuyama said. “Contrast that to people who support IEX: brokers, pension funds, investment funds — some of the most sophisticated investors in the world.”

Follow me: @jrkoren

MORE BUSINESS NEWS

A backup plan may set your job search up to fail

Whistle-blowing: Insurer gets smacked for bullying employees

The Redstones’ war with Viacom ends: Philippe Dauman resigns, Tom Dooley elected new CEO

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.