PUC dithers as consumers keep paying to ‘run’ crippled San Onofre

Welfare is a deadening system, at least according to the discussion being waged these days in connection with the presidential campaign. It saps ambition, discourages enterprise, allows the undeserving to sit on their haunches endorsing checks. We all know the talking points.

So why aren’t we more outraged by the $54-million welfare check going out every month to the shareholders of Southern California Edison, courtesy of the utility’s ratepayers? That’s how much Edison is collecting every month to operate its San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station.

The joke, of course, is that San Onofre isn’t operating.

Thanks to a thoroughly botched $770-million equipment “upgrade,” the plant hasn’t been online since January and may not operate ever again. The best-case scenario is that it might get restarted sometime around the end of this year or early next, but there’s no guarantee that it will run at full strength even then.

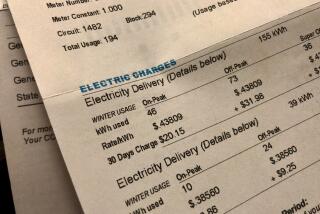

Meanwhile, the ratepayers keep paying. Over the more than six months that San Onofre has been dark, the bill has come to $25 for every Californian in its service district, man, woman and child. The old adage that “you get what you pay for” apparently doesn’t apply in Edisonland.

This situation is one of the reasons that we have the Public Utilities Commission in California, vested with the authority to examine utility operations and judge how much of their costs should be borne by customers rather than shareholders. What’s the PUC doing about this?

Glad you asked. The answer is nothing. The commission is planning to wait at least until the end of October, and possibly not for an additional six weeks after that, before deciding whether to take San Onofre out of Edison’s rate base. The law says, however, it could act today.

The law also says, however, that rate-making can’t be retroactive. As a result, Edison gets to keep every dime forked over before then for this nonfunctioning plant. Refunds to ratepayers aren’t permitted.

One body that has sounded the alarm about San Onofre costs is the PUC’s Division of Ratepayer Advocates. On Aug. 13 the division sent a letter to the PUC proposing that San Onofre be removed from utility rates instantly.

What did the PUC do about that request? Glad you asked. The answer is nothing. That’s also within the commission’s authority. It doesn’t have to comply with any requests from the ratepayer advocate. The advocates division can intervene in existing rate cases and PUC investigations as a consumer representative, but it can’t launch cases on its own. Indeed, the PUC doesn’t actually have to respond to the division at all. And in this case it hasn’t.

The bottleneck seems to be PUC Chairman Michael Peevey, a former Edison president whose chummy relationship with the company and the energy industry has drawn objections from consumer advocatesfor years.

The standoff underscores a major flaw in California’s utility regulations. Put simply, the division of ratepayer advocates has no power.

This isn’t unique among utility ratepayer advocacy bureaus, which have been established in 39 other states. The authority of most of them appears to be limited to intervening in existing rate cases or involving themselves in service-quality and consumer-protection issues. But at least 14 operate out of their states’ attorney generals’ offices, which suggests that they also can act proactively.

In some states, moreover, the public utilities commission can’t simply turn its back on the ratepayer advocate, as the PUC can in California. In Massachusetts, for instance, utility regulators must open an investigation requested by the attorney general’s office of ratepayer advocacy if it involves gas or electric rates.

In the San Onofre case, the California ratepayer advocate has raised some important points about what’s happened at the plant and the PUC’s legal responsibility. “It’s very simple,” Joseph P. Como, acting head of the division, told me last week, “though people are trying to make it complicated.”

The plant, which sits in all its billowy glory on the coast just south of San Clemente, hasn’t operated at full strength since Jan. 9, when its Unit 2 was shut down after a radiation leak. Unit 3 was shut down Jan. 30. Neither unit has generated power for customers for a single day since then.

The culprits are 2-year-old steam generators that may have been poorly engineered, poorly installed or both. Federal nuclear regulators are investigating. The problems may be so severe that it won’t make economic sense to restore the nuclear plant to service.

Edison says its rate charges associated with San Onofre run to $650 million a year, including operation and maintenance, the amortization of construction costs, and its permitted “return on investment” or, essentially, profit. Customers aren’t yet paying for the $670-million generators; how much they should pay for these hunks of useless metal will be the subject of a future rate fight. But other than that, they’re paying for San Onofre as though it were alive, not dead.

Because San Diego Gas & Electric Co. is a minority owner of the plant, its shareholders also are being gifted with cold cash by ratepayers. Between the two utilities, the total giveaway is $60 million a month, or more than $2 million a day, the division observes. So far, the bill has come to more than $390 million. An additional unrecoverable $240 million could flow to utility shareholders if the PUC waits the maximum period before acting.

And let’s not forget the cost of all the extra electricity Edison and SDG&E; have had to buy to compensate for San Onofre’s lost capacity during this steamy summer. As of June 30, they had spent a net $140 million in excess charges for the replacement power. Another legal fight is looming over whether shareholders or ratepayers should be stuck with that bill.

Under state law, Edison is required to formally notify the PUC once a facility is out of service for nine months; that deadline would be early October for Unit 2 and the end of that month for Unit 3. The PUC has an additional 45 days to launch an investigation into whether to remove that facility from the rate base — that is, to stop charging customers for its costs. Once it opens the investigation, the facility costs are subtracted from rates, with the understanding that some or all the charges might be restored once the PUC inquiry is complete.

Peevey has hinted that the PUC intends to wait until at least the nine-month period has passed. The ratepayer advocates point out, however, that under the law the commission can examine the service status of a power plant any time it wishes.

That’s especially relevant in this case because there’s no dispute that San Onofre is out of service. “By waiting, they’re hiding behind this nine-month proviso,” says Mark Pocta, the ratepayer advocates division’s program manager. “But nothing precludes them from acting sooner.”

The nine-month rule, he says, is aimed at modest outages that might fly under the radar indefinitely, unless utilities were legally bound to disclose them after a decent interval. As the division observed in its Aug. 13 letter, the rule is “not intended to be a free pass for utilities to earn a return on nonfunctioning hardware for nine months or more.”

The division’s request is way overdue. Como says his division asked the commission to take San Onofre costs out of customers’ rates only after it became incontrovertible that the plant shutdown was total and open-ended.

The request landed on the commission’s June 21 agenda, but it was deferred by Peevey. “He said they’d take it up later this year,” Como says, “but that’s a little too ambiguous for our comfort level.”

In waiting, the PUC seems to be applying an unnecessarily narrow interpretation to its authority. “There’s a process in place for us to follow, and that’s what makes the most sense,” says Ed Randolph, head of the PUC’s energy division, who returned my call to Peevey. “When you follow procedure, there’s less potential for litigation.” Edison says it shares the commission’s pious devotion to “procedure.”

Yet the potential costs of waiting are all on the consumers’ shoulders. If the PUC were to remove San Onofre costs from the rate base now, pending a complete investigation, it always would have the authority to reinstate any legitimate charges it identified, and retroactively. But if it dithers, there’s no way to rebate unwarranted charges already paid by customers.

Would you say that protecting consumers from $2 million a day in unwarranted charges is worth the threat of litigation? Me too. So the PUC’s resistance to acting now is mystifying. The utilities’ customers have already been cursed by the shoddy work that brought San Onofre to its knees in the first place. The commission’s inaction is rewarding their tormentors.

Michael Hiltzik’s column appears Sundays and Wednesdays. Reach him at mhiltzik@latimes.com, read past columns at latimes.com/hiltzik, check out facebook.com/hiltzik and follow @latimeshiltzik on Twitter.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.