How I Made It: This billionaire once thanked two of his employees with $1-million checks

- Share via

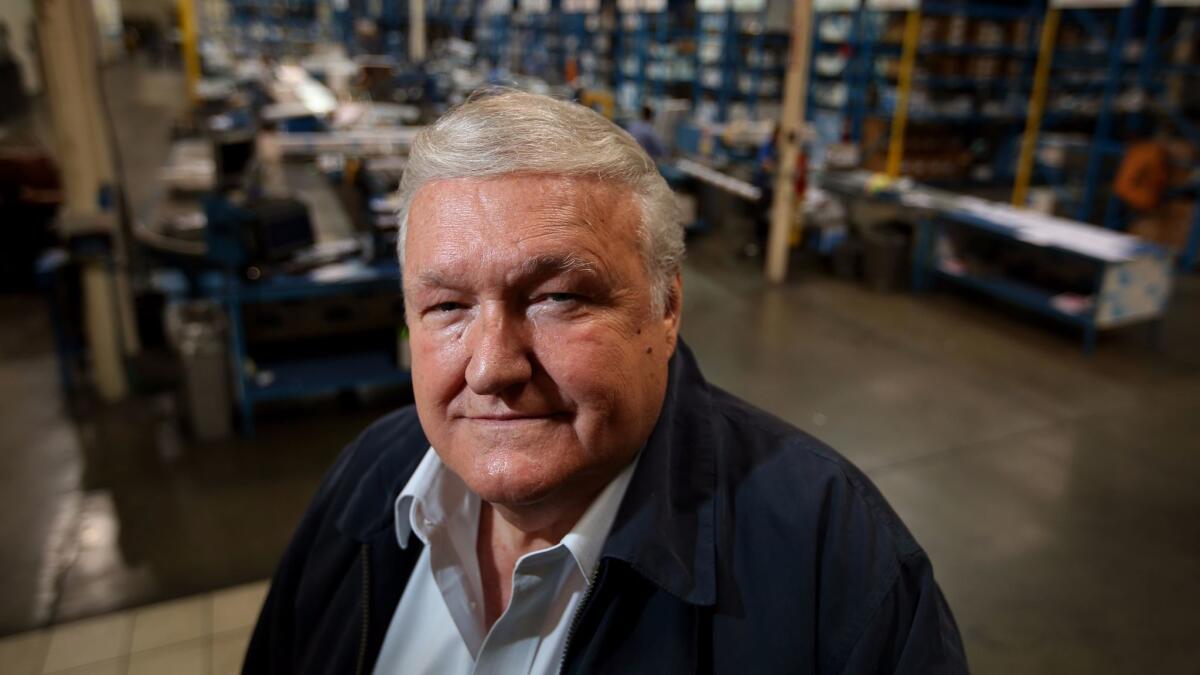

Donald Friese is chief executive of C.R. Laurence, a Vernon company that manufacturers and distributes tools and parts used by glazing companies — think window frames and hinges for glass shower doors. It’s not a sexy business, but it’s one that, over the course of five decades, turned Friese, 76, into one of the world’s most unlikely billionaires.

Friese’s story is about as rags-to-riches as it gets.

Learning to work

“I had one of those crazy lives,” Friese said. “I don’t talk about it a lot.”

He was born in 1940 in York, Pa., the third of his parents’ 13 children. And when he was 5, his parents took him and one of his brothers to an orphanage.

“They had very little. I think they really didn’t have the wherewithal to raise us,” he said. At age 12, he went to live and work on a dairy farm, then to a hog and vegetable farm. “In those days, all the farmers were like foster parents. That’s where I learned about work. I would work from sunup to sundown.”

Friese’s parents weren’t total strangers to him, but close to it. If this bothers Friese, he doesn’t let on. “If you never had something, you can’t miss it,” he said. “I didn’t have any choice in the way I came in, but I sure as hell have a choice about which way I’m going to go out.”

Learning to get along

After graduating from high school, Friese immediately enlisted in the U.S. Army. It was 1958, after the Korean War and before American troops went to Vietnam. Friese was trained as a missile mechanic and was stationed in Taiwan and Okinawa.

Compared to life on the farm, Friese found military life eye-opening. “I had more freedom in the service than I’d had in my life. But the nicest part was the people. I was exposed to a lot of people from every place in the United States. It helped me learn to get along with people.”

I didn’t have any choice in the way I came in, but I sure as hell have a choice about which way I’m going to go out.

— Donald Friese

‘Girls in bikinis’

After his three-year stint in the Army, Friese was at loose ends, with $125 in his pocket, no job and no plans. But a friend of his had a car, and both were interested in heading to the West. “There were girls in bikinis on the beach, and I said, ‘That looks a lot better than the damn farm in Pennsylvania.’ ”

After arriving in Los Angeles, Friese got an entry-level job at C.R. Laurence, which at the time had a single location at 7th and Mateo streets in what’s now downtown L.A.’s trendy Arts District. He started out earning $2.50 an hour.

He learned to do just about everything at the glazing-supplies company, including ordering supplies, assembling catalogs and working with customers. “I did everything I could possibly do to make the customers want to do business with us,” Friese said.

Buying in

He did it so well that after a few years, C.R. Laurence’s owner, Bernie Harris, offered to sell Friese a stake in the company. Friese figures that Harris saw him as not only a good worker and an asset to the company, but also as potentially something more. “He woke up one day and thought, ‘We can become competitors or partners.’ I guess he’d rather have me with him than with someone else.” Friese bought a 10% stake in the company for about $10,000. He steadily increased his investment and bought Harris out when he retired about 20 years ago.

In command

Over Friese’s long tenure with the company, C.R. Laurence acquired other distributorships and parts manufacturers, eventually becoming the country’s largest supplier to the glazing industry.

In 2015, the company was on track for annual sales of $570 million — up from about $240,000 when Friese started. The company now has 40 locations, including outposts in Germany, Australia, Denmark and Canada.

A few years ago, like his predecessor, Friese decided that it was time to look for a buyer — and not just any buyer. “I woke up one day and I was 70 years old,” he said. “What am I going to do with this thing? We have 1,700 employees, almost 1,800. I want them to have jobs and be able to make money.”

A few private equity firms were interested, but Friese opted to sell to CRH, an Irish conglomerate that sells all manner of construction materials. The company paid $1.3 billion in cash for Friese’s company.

As part of the deal, Friese kept ownership of most of C.R. Laurence’s real estate and stayed on as chief executive. “They told me they’d let me have a stand-alone business and let me run it, and they did.”

Better than a thank-you note

Friese believes in actions more than words. As such, he’s not big on thank yous. “I always hated people saying, ‘Well, you did a good job, so thank you.’ Thank you doesn’t help my children get a house or schooling.”

So when Friese sold the company, he used more than $86 million of the proceeds to pay bonuses to the roughly 1,400 employees who had been with the company more than a year. That’s more than $60,000 on average. Some got much more. Friese remembers two in particular — longtime workers who run some of his warehouses.

He called them into his office and told them he sold the company. “And I said, ‘I don’t think thank you is good enough,’ and gave each of them $1 million. We were all crying. There are some people who you know do more for you than is required. These guys are those kinds of guys.”

Six days a week

Though he’s worth more than $1 billion, Friese still goes to work six days a week. He’s in the office at 6 a.m. most days and is back home in Chatsworth — in the same home where he and Andrea, his wife of 53 years, have lived for nearly three decades — by 6:30 p.m. On Saturday, he heads home at noon.

“This is my life,” he said. “There’s nothing like being successful in what you do. It really is very satisfying. I’m going to work as long as I can.”

In the meantime, Friese is also figuring out what to do with his massive net worth. Whatever happens, he said he wants to make sure not to give too much to his three grown children. “We’re trying to figure that out and work on a plan. We love to give to charity, and that will be a major factor. I don’t want to give our kids too much money.”

One splurge

“Having money doesn’t mean you have to spend money,” Friese said, although he acknowledges that he made one big splurge after selling the company.

He bought a house in Malibu, something he said his wife had always wanted. “We try to go there on weekends. She gets upset with me because I don’t go up there often enough.”

Twitter: @jrkoren

ALSO

John Burns, real estate guru, joined the industry by 'accident'

Penthouse CEO Kelly Holland wants to revive the legendary adult entertainment brand

How being thrown into the deep end by Mark Zuckerberg prepared Aditya Agarwal to lead

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.