St. John’s hospital foundation sues to enforce donation pledge

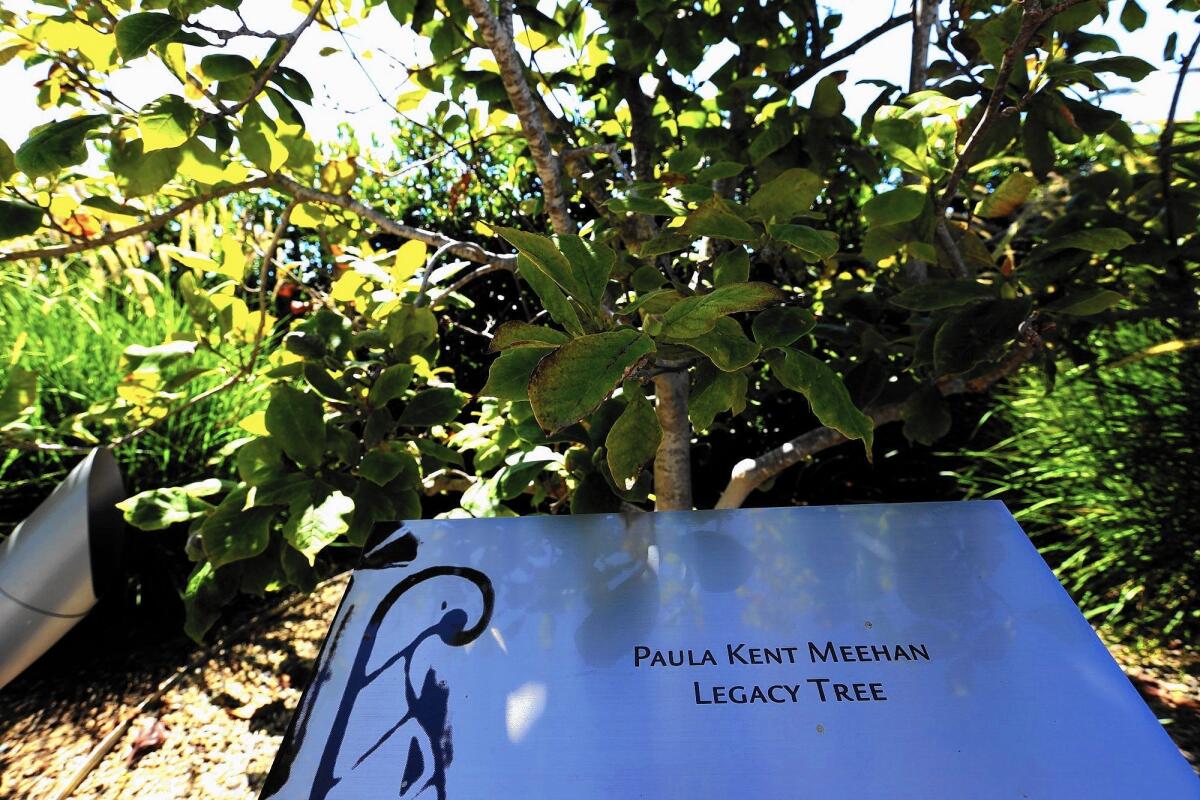

A magnolia tree dedicated to benefactor Paula Kent Meehan at St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica.

- Share via

Paula Kent Meehan made a fortune after launching the Redken hair-care products company in the 1960s. She spent the last years of her life giving that money to charity.

One of the biggest beneficiaries was supposed to be St. John’s Health Center, a storied Santa Monica hospital founded by Roman Catholic nuns that has cared for celebrity patients such as Michael Jackson, Elizabeth Taylor and President Reagan.

But in 2013, Meehan revoked her pledge to the St. John’s foundation after the ouster of the hospital’s top executives and the proposed sale of the nonprofit Catholic hospital. And now the hospital’s foundation is suing her estate for the $5 million that she originally promised.

The suit marks a rare test of whether charities can legally enforce donation pledges, a move that many philanthropic experts call uncouth and unwise. Fighting with one donor can drive away others who might want to share their wealth, they cautioned.

“From a practical or public relations perspective, I couldn’t imagine a worse strategy,” said Doug White, director of the master’s in fundraising management program at Columbia University. “This is not the way an organization should behave with a donor. It sends a very bad message.”

Manners and messages aside, the St. John’s foundation may well have a legal claim to the money. Meehan signed an “estate pledge commitment” that said her promised gift would be “legally binding on me and my heirs, executors, administrators, personal representatives and assigns.”

The organization has to weigh the risk of offending other donors against the large amount of money involved, said Howie Pearson, a Stanford University attorney and professor of estate planning at its law school.

“The charity is caught: On the one hand, you want to be donor friendly; on the other hand, the charity does have a fiduciary obligation to protect its assets,” he said.

Robert O. Klein, president and chief executive of the St. John’s foundation, said the organization is “eternally grateful” to its donors.

“They are the lifeblood of our hospital,” he wrote in an email response to questions from The Times. “When a donor irrevocably pledges to make a gift, it is vital to our planning and budgeting that the gift is fulfilled.”

Meehan died last year at 82. She originally promised the money in 2007 to the foundation, which says it supports the hospital’s “mission of compassionate care” and funds cancer research. To recognize that gift, St. John’s planted a tree on its grounds in Meehan’s honor and put her name in the hospital lobby along with other big donors.

After her death, the foundation wrote to Meehan’s representatives and demanded the money. When they refused to pay, the foundation sued the executors of her estate for breach of contract for $5 million.

“Clearly they thought about it and thought it was worth the risk,” said Richard Marker, who founded New York University’s academy for grantmaking and funder education.

“It’s certainly a bad-taste question,” he said, “but bad taste is not the law.”

In the lawsuit, filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court, the foundation pointed out that it paid to plant and maintain the tree in Meehan’s name, added her name to the donor wall and published a story about the donation in a newsletter.

“The recognition and positive publicity received by Ms. Meehan during her lifetime … was material and was a bargained-for exchange,” the hospital foundation said in the lawsuit.

The foundation’s lawsuit seeks damages from Meehan’s charitable foundation and from the executors of her estate, Wendy Karzin and Marcia Hobbs. Both women declined to comment, as did their attorney, Alex M. Weingarten of the Venable law firm in Los Angeles.

Meehan, a former television commercial actress, was driven to create Redken because she grew tired of hair care products that damaged her hair and scalp. She founded the company with her hairdresser, Jheri Redding, in 1960 and acquired full control of the company a few years later.

Redken Laboratories Inc. grew into one of the largest hair care product companies in the world, with 850 employees and sales in 35 countries. L’Oreal acquired Redken in 1993 for an undisclosed price.

In the years to follow, Meehan focused on philanthropy, paying particular interest to animal welfare. She formed a pet rescue organization called Pets 90210 — the Pet Care Foundation, and she set aside $500,000 to develop a program at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center to bring patients’ pets to visit them.

In 2014, she bought the closed Fine Arts Theater in Beverly Hills, with the intention of reopening it for live performances, and the Beverly Hills Courier, a local weekly newspaper.

The $5-million pledge to St. John’s foundation was one of her largest philanthropic endeavors. Neither her representatives nor foundation officials would say what caused Meehan to change her mind.

She wrote the letter revoking the pledge in March 2013, less than three months after the hospital’s owner, the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth Health System, ousted the top two executives and the majority of its governing board.

In May 2013, the hospital company agreed to sell St. John’s to the Catholic chain Providence Health & Services. The sale closed last year.

A Providence spokeswoman declined to discuss the lawsuit, referring questions to the foundation.

The lawsuit follows a steep downturn in donations to the St. John’s foundation. The group reported that contributions fell from a peak of $30 million in 2010 to $6.6 million in 2013, according to a financial report filed with the Internal Revenue Service.

Contributions climbed to $14 million in 2014, the foundation said in a recent newsletter.

“Following a transitional year in 2013, we are experiencing a resurgence of giving, and many pledges have been brought current,” the foundation reported. “We are pleased to have addressed donors’ questions and can confidently report that our future is bright.”

It is not uncommon for charities to go to court to fight for promised donations, but most often that happens when heirs oppose a loved one’s charitable pledge — not when a donor decides to rescind, White said.

In 2002, relatives of a large donor sued Princeton University, contending that it had failed to honor the intent of a $35-million gift made in 1961 that had grown through the years to about $900 million. The money was intended to train graduate students to enter government service but had been spent on other items, the family said.

After a legal battle of more than six years the two sides settled, with the university keeping the money but agreeing to cover legal expenses and to spend $50 million to create a new foundation.

This year a 98-year-old Newport Beach philanthropist sued Chapman University, alleging that the college coerced him into donating $12 million and then failed to keep its promises. The university denied the allegations.

The legal issues between St. John’s foundation and Redken’s representatives could eventually be resolved by a judge or jury.

“It seems to me to be right on the border,” NYU’s Marker said. “That’s why you have courts.”

Twitter: @spfeifer22

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.