Hydroelectric power is poised for comeback in California

- Share via

California’s years-long drought put hydroelectric power flat on its back.

But one of the cleanest and cheapest energy sources may be poised for a comeback as the state has been drenched with rain and its mountains blanketed in snow in recent months.

Energy officials studying the numbers are cautiously optimistic the sector’s output may roar back to levels seen before drought decimated watersheds, streams and reservoirs.

Such a turnaround may not make a big difference in electricity bills because many factors go into what consumers pay, experts said. Instead, the major benefit would come in the form of less air pollution.

If the wet winter translates into a productive late spring and early summer for hydro, utilities will probably use less natural gas, the most commonly used energy source in the state’s power mix.

“I think that would be the trade-off you would see — greater use of hydro and little bit lower use of natural gas,” said Andy Smith, senior utilities analyst for Edward Jones.

The drought caused a dramatic drop in hydroelectricity production.

Take 2011 as an example. That was a very wet year for the state, and according to figures from the California Energy Commission, more than 18% of California’s in-state generation came from large-scale hydropower plants. Natural gas accounted for 45%.

But in 2015, the most recent year examined by the commission, the drought sent the hydro sector’s in-state generation down to 5.9% while natural gas shot up to 59.9%.

The growing production from other renewable energy sources such as wind and solar helped absorb some of the deficit created by hydro’s downturn, but natural gas soaked up more of it. Natural gas accounted for more than twice the generation of renewables in 2015.

Natural gas burns two to three times cleaner than coal, so California has essentially banished coal-fired electric plants. Still, natural gas is a fossil fuel that produces carbon dioxide, a primary global warming gas.

A study released last year by UC Irvine researchers estimated the state’s electricity sector generated 33% more carbon dioxide annually between 2012 and 2014 than it did during the wet year of 2011 as natural gas use went up and hydro went down.

The Pacific Institute, an environmental research group based in Berkeley, came out with its own study saying the drop in hydro forced Californians to pay an extra $2 billion in electricity costs between 2011 and 2015 because natural gas is more expensive than hydropower. The study also estimated that greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector increased by 10%.

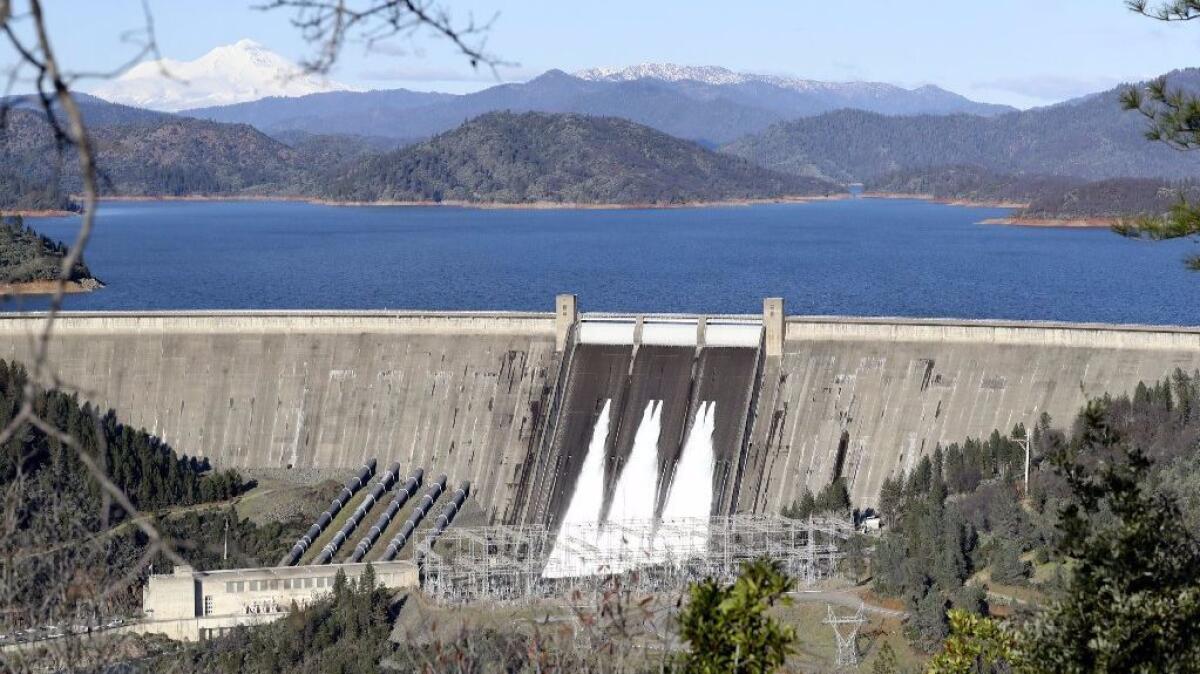

The state’s largest hydroelectric plant is Shasta Dam, which can hold 4.5 million acre-feet and generate 710 megawatts — enough to power more than half a million homes.

As of last week, Shasta Dam was at 130% of its historic capacity.

In the most recent data from the U.S. Drought Monitor compiled by the federal government, no parts of California were in extreme or exceptional drought. Last year at this time, nearly 61% of the state was at those levels.

“We do expect to see more hydroelectric output, at least for the summer peak of 2017, than we did in 2016,” said Steven Greenlee, spokesman for the California Independent System Operator, or Cal-ISO, which oversees the operation of about 80% of the state’s electric power system, transmission lines and electricity market.

Yet Cal-ISO officials are cautious.

Rain does not matter as much as the mountain snowpack that runs off in the late spring and early summer, Greenlee said. One risk is that extreme heat in the spring could melt the snow too quickly, causing water to flow faster than generators can take advantage of it.

Although the snowpack totals look promising, Cal-ISO won’t issue its grid stability forecast until late April or early May.

“It depends on what our demand will be,” Greenlee said. “Are we going to be looking at a really hot summer where we really lean on hydro or is the forecast going to be for a milder summer where demand isn’t going to be quite so high? Those are things we don’t quite have the answers to yet.”

Too much moisture at the Oroville Dam near Sacramento led to the evacuation of almost 200,000 residents and, to a lesser degree, highlighted the interdependence among various sources that make up the state’s power grid.

The damage from the spillway at Oroville forced the shutdown of its 819-megawatt plant, which is slowly returning to service. How to make up for the loss? By using other sources, including natural gas.

Although hydroelectric dams can be expensive to build, once they are completed, the cost of generating power is cheap, often coming in as the least expensive option for electricity generation.

The Sacramento Municipal Utility District is one of the largest producers of hydroelectricity in the state. In 2015, a dry year, it pegged its costs for hydro at 3.2 cents a kilowatt hour, compared to 6.1 cents a kilowatt hour for natural gas.

It’s not unusual to see hydro projects across the country coming in at 2 cents a kilowatt hour.

So if hydro makes a big comeback this year, why do some experts think any discount on ratepayers’ electric bills pack would be modest?

First, hydro peaks in the spring and early summer when snow in the mountains melt. But electricity demand doesn’t reach its apex until later in the summer, when hot weather prompts utility customers to turn on air conditioning.

What’s more, rates are set on a forward-looking basis so they have already been set for this year. Any reductions would not show up until next year’s bills.

Another factor is that energy sources are constantly adjusting to forces of supply and demand.

“Everything doesn’t stay equal,” said Rob Anderson, director of resource planning at San Diego Gas & Electric.

“As an example, if there’s a lot less demand for natural gas, the price for natural gas will fall,” Anderson said. “But some producers of natural gas may say, hey, the price is too low, I’m going to cut back on production. So they would decrease the supply, bring things back up to the current price and, in essence, cancel out the effect of hydro.”

In addition, natural gas prices are historically low. With U.S. drillers employing hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques, the supply of natural gas in the U.S. has increased, keeping a lid on wholesale prices for going on nine years.

And a warm winter in other parts of the country has weakened demand, leading to a glut of natural gas.

When it comes to the average retail price of electricity, California finishes sixth-highest in the country and fourth-highest for states in the continental U.S., at 15.42 cents a kilowatt hour.

On the bright side, the state consumes less electricity per household than most states. That’s partly due to mild weather along the coast but also to greater efficiency from household appliances and less heavy manufacturing.

As a result, the average monthly bill in 2015 in California was almost $20 less than the national average.

Nikolewski writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

rob.nikolewski@sduniontribune.com

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.