MannKind developing inhalable epinephrine to challenge Mylan’s EpiPen

- Share via

A Valencia drugmaker that has tried to convince diabetics to inhale rather than inject their insulin is working on a product that will make a similar pitch to a new group of patients: severe allergy sufferers who rely on Mylan Pharmaceuticals’ pricey EpiPen.

Even as it struggles to ramp up sales of its Afrezza inhalable insulin, MannKind Corp. is now in the early stages of developing an inhalable form of epinephrine that aims to take market share from the injectable version at the center of a storm over drug pricing.

It’s a product that would bring more competition to the emergency epinephrine market dominated by the increasingly expensive EpiPen, and could give allergy sufferers a needle-free option — something that could appeal especially to children and their parents, said Michael Pistiner, a pediatric allergist in Boston.

“Some people have been a little nervous about, for instance, giving a child an intramuscular injection,” Pistiner said. “Finding alternative methods is something people have been very interested in.”

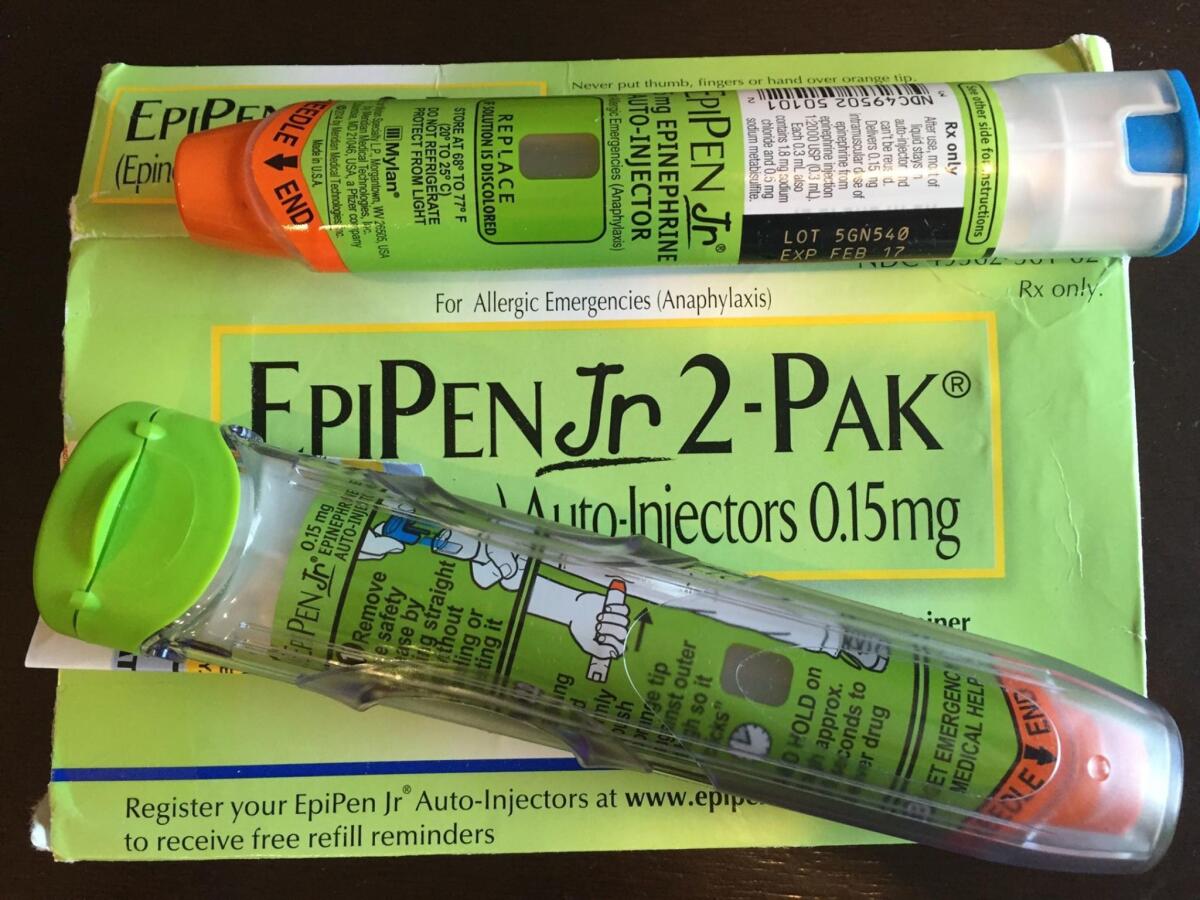

Epinephrine is used to combat anaphylaxis — life-threatening allergic reactions to food, insect bites and other allergens. The EpiPen allows patients or aid givers with little to no training to quickly inject epinephrine, typically into the thigh, boosting low blood pressure and opening restricted airways.

Though an inhalable version could hold promise, MannKind must get the product approved and into the hands of patients, a big task for a company short on cash after its Afrezza inhaler took more than a decade to bring to market, only to record disappointing sales.

“It would be a difficult process,” said Joel Hay, a professor of pharmaceutical economics and policy at USC. “I don’t know if MannKind has the time and funding resources for that.”

What’s more, the company lost its deep-pocketed founder earlier this year.

Alfred Mann, an entrepreneur who founded more than a dozen companies, died in February at the age of 90. He poured nearly $1 billion of his own fortune into MannKind to help the company develop Afrezza, twice rejected by the Food and Drug Administration before finally getting approval in 2014.

Once thought to be a potential blockbuster, sales of Afrezza didn’t meet expectations during its first year on the market. In January, French drug giant Sanofi, which had agreed to market and distribute Afrezza, scrapped its deal with MannKind, leaving the small company to sell the drug on its own.

Shares of publicly held MannKind, which were trading at more than $10 after the FDA signed off on Afrezza, are now valued at about 74 cents.

As of June 30, the company had $63.7 million in cash, enough to stay afloat into the first quarter of next year, Chief Executive Matthew Pfeffer told analysts last month. That’s when MannKind expects to file an application with the FDA and potentially begin clinical trials of its inhalable epinephrine.

Financially, the question for MannKind is whether sales of Afrezza can pick up enough over the rest of this year to offset the potential cost of clinical trials for the new product. Pfeffer said that question should be answered well before the company would hope to start new trials.

“I think we’ll know the future of Afrezza before we get to that stage,” he said.

Another option might be for the company to find a strategic partner — a prospect made more likely by the intense media coverage of Mylan’s series of steep increases in the price of the EpiPen, from about $50 per shot in 2007 to more than $300 today.

“There’s a lot of interest in [EpiPen] alternatives,” he said. “It’s not inconceivable that we could get a partner to help us with the funding of that trial. That’s not our current game plan, but it’s something we could consider.”

MannKind also expects that the clinical trials would take much less time than those for Afrezza, which needed to prove that long-term use did not decrease lung function. That was a problem with an earlier inhalable insulin developed by Pfizer that was pulled off the market.

When the FDA approved Afrezza, it required a warning that it should not be used by people with asthma and other lung conditions. But diabetics may take insulin several times a day, while life-threatening allergic reactions are generally rare events.

“It’s hopefully something you never have to use, which makes that less of an issue,” said Pfeffer, who hopes clinical trials could begin and end next year, with the product hitting the market by late 2018.

MannKind is developing two other inhalable drugs, one that treats nausea in patients undergoing chemotherapy and another to treat a cardiovascular disease called pulmonary arterial hypertension, but epinephrine is the priority.

The company started work on epinephrine about a year ago, long before the recent spate of news stories about the EpiPen price increases. While it’s not clear how much a dose of inhalable insulin might cost, Pfeffer said the product would almost certainly be cheaper than EpiPen.

Pistiner, the pediatrician and a co-founder of food allergy information site AllergyHome.org, said more options for emergency epinephrine users should lead to competition and lower prices.

“The more alternatives, the more competition there will be,” Pistiner said. “Hopefully we’ll get back to an affordable and reasonable situation.”

But he noted that MannKind will have to overcome a few obstacles if it hopes to bring such a product to market.

He noted a study that showed it’s difficult to get enough epinephrine into the body by inhaling it — though that study looked at older epinephrine inhalers used to control asthma attacks. Pfeffer said MannKind’s product would carry a stronger dose of epinephrine aimed specifically at stopping anaphylaxis.

Pistiner also said that respiratory symptoms, such as shortness of breath, often accompany severe allergic reactions. If someone can’t breathe, an inhaler doesn’t do much good.

“Most kids who experience anaphylaxis have respiratory [symptoms],” he said. “That’s a very real challenge.”

Pfeffer said MannKind is aware of that issue, but that since respiratory symptoms typically don’t start until several minutes into an anaphylactic attack, there would be time to use an inhaler before symptoms become life-threatening.

“Most people want to be pretty sure before they stab themselves in the leg with a big needle,” he said. “That’s often why people wait too long. We thought we could put epinephrine into a form that’s not as intimidating to people so that people would use it sooner in the process with less hesitation.”

Follow me: @jrkoren

ALSO

Can YouTube make it big on the small screen?

Rabies treatment shows why U.S. healthcare is hard to swallow

Shipper Hanjin moves to resolve cargo chaos

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.