Column: Cutting healthcare costs shouldn’t be this painful

- Share via

When my son was circumcised, Sade’s “Love Is Stronger Than Pride” was playing on a radio at the hospital. The pediatrician glanced over at me and said, “Some day, he’ll hear that song and won’t know why it makes him uncomfortable.”

Snip.

I recalled this experience while speaking the other day with Matt Williamson about his own son’s quiet storm of foreskin loss. The issue wasn’t the procedure, which I know some people question. The issue was the cost.

Williamson, 43, wanted to know why Kaiser Permanente’s South Bay medical center apparently charged him more than $3,000 when a nearby private clinic charges as little as $175.

“They never told us beforehand how much it would cost,” the Manhattan Beach resident told me. “They just gave us a piece of paper with mainly religious stuff and some health studies. If they had said it would cost $3,000, I would have immediately said, ‘No, thank you.’ I think most people would.”

This is yet another example of the lack of transparency in medical pricing, and the fact that hospital charges for routine tests and procedures can be orders of magnitude more expensive than those of specialized clinics – although patients typically will find that out only after they’ve paid their bill and realize they’ve been fleeced.

“These such huge price disparities show how uncompetitive the healthcare market is,” said Mireille Jacobson, director of the Center for Health Care Management and Policy at UC Irvine’s Merage School of Business.

“All these high-deductible health plans give patients an incentive to find the best price,” she said. “But the reality is that it’s very hard to shop around.”

I wrote earlier this month about a woman who was charged an insured rate of about $80 apiece for a handful of blood tests at Torrance Memorial Medical Center. She found out afterward that if she’d paid cash, the tests would have run closer to $15 each.

Cash prices are intended for uninsured people and usually will be significantly more expensive than insured rates. But experts say growing competition for routine healthcare such as lab work or MRIs has prompted many hospitals to lower their cash prices below what’s charged to insurers.

The average hospital cost of a circumcision nationwide is about $2,000, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. However, many insurance plans treat the procedure as elective and thus won’t cover it unless medically necessary.

At UCLA, the “list price” for a circumcision is $1,205. A spokeswoman said the uninsured cash price is $844. Cedars-Sinai and Sutter Health say they don’t charge extra for the procedure.

Kaiser also says there’s no extra charge for circumcisions, even though its bills may say otherwise.

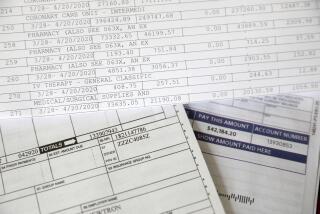

Williamson’s coverage has an annual family deductible of $9,000. The total bill for his son’s delivery was $13,179, of which he was responsible for $8,207. The bill included an itemized $4,773 charge for “circumcision using clamp/other device,” which translated to an out-of-pocket cost of $3,077.

Williamson subsequently heard about a Culver City clinic called Gentle Circumcision. That’s all they do. The all-inclusive price for newborn circumcision – including an initial consultation, the procedure and all follow-up visits – is $175.

Jessie Morales, a medical assistant at the clinic, told me they handle about 20 babies a day.

“We don’t go overboard,” she said. “We try to be economical. We’re basically just charging for the doctor’s time and any supplies used.”

I asked Morales why the prices at Gentle Circumcision are so much lower than what many hospitals charge.

“I really don’t know,” she answered. “There’s no difference to the methods we use compared to what they do.”

Shana Charles, director of health insurance studies at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, said a small clinic has nowhere near as much overhead as a large hospital, so it’s not surprising that the clinic’s costs would be lower.

Even so, she said a growing number of Americans will find themselves in situations similar to Williamson’s because more people are shifting to high-deductible insurance plans. The upside of such plans is that monthly premiums are lower. The downside is that the patient is responsible for a much greater share of healthcare costs.

“The problem is no longer people being uninsured,” Charles said. “The problem now is that people are underinsured.”

For that reason, she said, “it’s very important, if you have a high-deductible plan, that you shop around. You’ll find a wide range of prices out there.”

That often won’t be an option. No one haggles during an emergency.

A circumcision is a different matter. Once the baby’s gender is known, a couple can have months to prepare for delivery. Also, a circumcision doesn’t have to be performed right away. The procedure can safely be done within 10 days of birth, according to the Mayo Clinic. The American Academy of Pediatrics says the health benefits of circumcision outweigh the risks.

Sandra Hernandez-Millett, a Kaiser spokeswoman, said by email that the cost of newborn circumcision “is a benefit included within the total cost of labor and delivery” and that “no patient would be charged $5,000 for an infant circumcision at Kaiser Permanente.”

So how does she explain the $4,773 line item on Williamson’s bill?

“It’s possible that in a computer printout of costs, the entire operating room cost may be consolidated into one line item and circumcision may show up as the description,” Hernandez-Millett said. “That doesn’t mean that circumcision was the cause of the cost. It just means that line items displayed on the computer printout may not have included all the detail of everything that took place.”

I’m not sure that’s a very good explanation. Williamson’s bill has 25 itemized charges, including a $3,716 charge for “delivery.”

“We are always looking to improve our processes so that we avoid causing confusion,” Hernandez-Millett said, “and we’ll use this example as part of that ongoing effort.”

Kaiser might also give a little thought to how it communicates with members.

Williamson said that after he received his bill, he wrote to Kaiser challenging the circumcision cost and requesting a lower price. He said Kaiser wrote back denying his appeal.

“They said I never paid for the circumcision, and that’s all they said,” Williamson recalled. “So I wrote back to say that my bill clearly shows a charge for circumcision.”

That was in February. As of Thursday, he was still awaiting a response.

David Lazarus’ column runs Tuesdays and Fridays. He also can be seen daily on KTLA-TV Channel 5 and followed on Twitter @Davidlaz. Send your tips or feedback to david.lazarus@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.