Column: Inside the effort by two Beverly Hills billionaires to kill a state law protecting farmworkers

Los Angeles-based Wonderful Co. — the world’s largest pistachio and almond grower, the purveyor of Fiji Water, Pom pomegranate juice and Justin wines, and owner of the Teleflora flower service — wants you to know that it’s committed to “sustainable farming and business practices” and sees its employees as “a guiding force for good.”

Wonderful’s owners, the Beverly Hills billionaires Lynda and Stewart Resnick, say their “calling” is “to leave people and the planet better than we found them.”

Here’s another side of the company. Since February, it has been engaged in a ferocious battle with the United Farm Workers over the UFW’s campaign to unionize more than 600 Wonderful Nurseries workers in the Central Valley.

‘We ask each of you firmly not to sign an authorization card.’

— Anti-union script read to Wonderful Nursery workers by company officials

Having lost a series of motions before the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board to delay a mandate that it reach a contract with the UFW as soon as June 3 or have terms imposed by the board, Wonderful on Monday unleashed a nuclear attack: a lawsuit seeking to have the 2022 and 2023 state laws governing the unionization process declared unconstitutional.

If it succeeds, California’s legal protections for farmworkers could be rolled back to conditions that prevailed before César Chavez’s campaigns for farm unionization in the 1960s.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“This is an attack on farmworkers’ rights,” says Elizabeth Strater, the UFW’s director of strategic campaigns. Farm employers “will do everything they can to prevent workers from empowering themselves and lifting themselves out of poverty.”

The company disputes the claim and says its relationship with agricultural workers “is rooted in mutual trust, collaboration and respect,” in the words of Wonderful Nurseries President Rob Yraceburu.

Wonderful’s lawsuit takes a page from arguments made against the National Labor Relations Board by Trader Joe’s and Elon Musk’s SpaceX. Both companies, facing NLRB regulatory actions, are contending that the NLRB, which Congress established in 1935, is unconstitutional.

Wonderful contends that provisions of the state’s agricultural labor code violate its rights of due process guaranteed by both the state and U.S. constitutions.

At issue is a UFW drive to represent more than 600 Wonderful Nurseries employees that began in early 2023. The UFW ultimately presented the labor board with signed cards from more than half the employees giving the UFW authority to represent them in collective bargaining on a contract, a process known as a “card check.”

The board certified the union as the workers’ representative on March 1, triggering a tight deadline aimed at prompting the union and the company to reach a contract.

After decades of defeats in its drive to unionize Southern auto plants, the UAW scores a big win in Chattanooga. Other plants are now in its sights

As often happens in hard-fought union campaigns, this one has generated a cross fire of allegations of unfair labor practices from both sides — the company asserting that the union defrauded workers into signing the representation cards, the union asserting that the company browbeat more than 100 workers into revoking their authorizations to drive the approval rate below the required 50%.

Accounts from the workers themselves vary. As my colleagues Rebecca Plevin and Melissa Gomez have reported, there have been complaints about poor working conditions at Wonderful along with hope that a union would help upgrade standards. Other workers say they misunderstood that signing an authorization card was tantamount to joining the UFW.

Some workers said they had second thoughts about signing the cards after meetings with a company-hired union-buster, Raul Calvo, who told them the union would take 3% of their pay for dues. In late March, some 100 Wonderful workers staged an anti-union protest at the ALRB offices in Visalia, but the UFW has alleged that the rally was the product of company coercion. Wonderful said at the time that it had no involvement in the protest and didn’t pay the workers for their time.

“These workers are so vulnerable,” the UFW’s Strater says. Many are undocumented or have other reasons to worry about job security, arguably making them receptive to management directives.

In this case, another party has weighed in — the Agricultural Labor Relations Board, an independent state agency. After an investigation, the board’s general counsel, Julia Montgomery, alleged that Wonderful trampled its workers’ unionization rights through numerous anti-union actions, including coercing them to submit declarations rescinding their authorizations. Wonderful has denied most of the allegations.

Wonderful says that the workers submitted their declarations — nearly 150 of them — voluntarily, “without any request having been made” by the company. Montgomery’s allegations, however, are mighty specific. She cites a series of meetings that were overtly aimed at persuading the workers to back away from the union.

That process began with employee meetings addressed by Calvo and proceeded to sessions in which workers met with Wonderful human resources personnel, Montgomery alleged. At those meetings, the company representatives read from a Spanish-language script stating that the union could have obtained workers’ signatures without their knowledge, that they would be deprived of the opportunity for a secret vote on unionization and encouraging them to sign a declaration revoking their authorization cards.

The National Labor Relations Board based its joint-employer rule on the reality of today’s workforces. So of course a Trump-appointed judge overturned it.

“We ask each of you firmly not to sign an authorization card,” the script read. In a line that sounds as if it came fresh out of the playbook of anti-union companies such as Starbucks, the script stated that the company wants “to be able to work one on one with you without the interference of a union.”

Some workers were led into a large conference room, where company representatives were assigned “to help the worker draft the declaration” revoking the authorization cards, Montgomery asserted. Some agents typed up declarations for the workers and handed them to the workers to sign.

A few words about the plaintiffs in this lawsuit:

The Resnicks are prominent philanthropists and political donors (mostly to Democrats). Their companies’ effects on the environment and California agriculture generally are checkered. Indeed, their most eye-catching charitable donation, a record-breaking $750-million pledge to Caltech in 2019 for research into climate change and “environmental sustainability,” isn’t inconsistent with a desire to “greenwash” some of their other activities.

As I previously wrote, while it might be churlish to suggest that the gift was devoid of genuine altruistic impulses, it would be naive to assume that altruism is the whole story.

A few years earlier, the Resnicks’ Justin Vineyards had been caught clear-cutting an oak forest near Paso Robles to make room for new grape plantings. The work was halted by San Luis Obispo County authorities, and the firm eventually agreed to donate the 380-acre parcel to a land conservancy.

Although the Resnicks say they are “dedicated to our role as environmental stewards,” their Fiji Water subsidiary looks like the antithesis of environmental sustainability. It profits from transporting water in plastic bottles more than 5,500 miles from the island nation to California and beyond, places that already have abundant water.

Wonderful’s pistachio and almond orchards have complicated efforts to apportion water among the state’s competing stakeholders. Because the trees require watering in wet years or dry, their acreage can’t be fallowed during dry spells.

That has made the water demand of the agricultural sector less flexible, and arguably has contributed to the devastating decline of the state’s salmon fishery and the drying out of rivers and streams that once supported a diverse population of fish and birds.

The UAW’s great new contracts with GM, Stellantis and Ford show that union solidarity and concrete goals bring major victories for workers for the first time in decades.

This isn’t the first time that the Resnicks have wrapped themselves in the U.S. Constitution to fend off a regulatory agency. In 2010, they asserted that the Federal Trade Commission infringed their 1st Amendment rights by holding that they made “false and misleading” and “unsubstantiated” representations about the health benefits of their Pom pomegranate juice, which amounted to unlawful marketing.

The company pitched the juice as “health in a bottle.” Wonderful put up billboards with the words “Cheat Death” next to a picture of the bottle. Its ads claimed Pom has beneficial effects on prostate cancer (“Drink to prostate health”), cardiovascular health and even erectile dysfunction — all of which claims were judged scientifically dubious by regulators. The company fought the FTC up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which rejected its appeal.

The 2022 and 2023 laws that Wonderful is challenging — indeed, the very creation of the ALRB in 1975 — reflect a reality known in California for more than a century: Bringing labor rights to farmworkers is notoriously difficult.

The first major farm union organizing drive in the state, among hops pickers in Wheatland, north of Sacramento, was broken up by four companies of the National Guard called out by Gov. Hiram Johnson in 1913. A statewide dragnet for organizers from the Industrial Workers of the World, or Wobblies, ensued, followed by hundreds of arrests. No further significant farm organizing took place for 16 years.

In 1975, a state law passed at the urging of César Chavez’s UFW gave union organizers the right to meet with workers on the farms where they toiled. But the Supreme Court, voting on partisan lines, struck it down in 2021—the law allowed organizers to “invade the growers’ property,” as Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote.

To address the heightened difficulty agricultural unions faced, the state Legislature established the card check process in 2022 and 2023. The laws incorporated a tight timeline governing certification and contract bargaining, and stipulated mandatory mediation if no contract is reached with a set period.

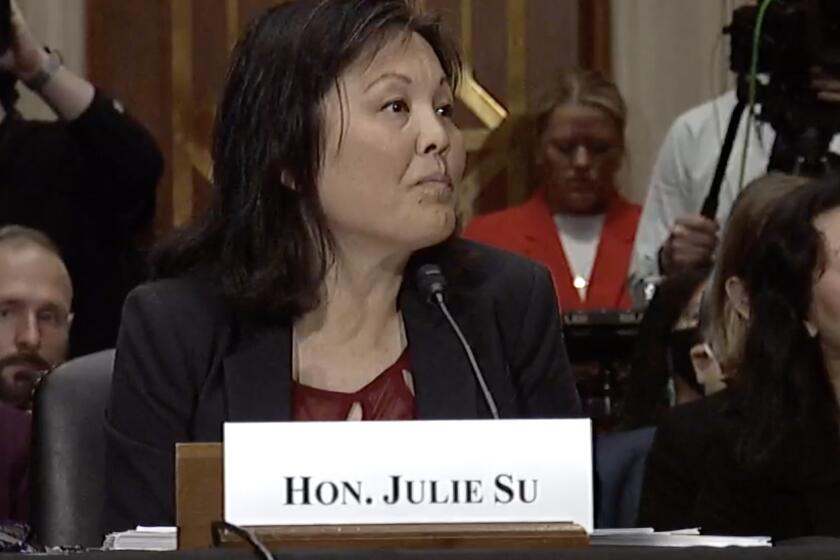

Julie Su’s accomplishments make her a spectacularly qualified nominee for Labor secretary. That’s exactly why Republicans — and some Democrats — will do their best to block her confirmation.

The goal was to address “the basic failing of labor law both at the federal and state level, which is delay,” said William B. Gould IV, professor emeritus of law at Stanford and a former chairman of the National Labor Relations Board and the state Agricultural Labor Relations Board.

“Delay works against the interests of workers and unions, because employers hope that they’ll grow weary,” Gould told me. The tight deadlines were designed to place the burden of delay on the employers.

Wonderful maintains in its lawsuit, filed in Kern County state court, that the accelerated process has deprived employers of constitutionally protected due process rights by allowing a union to be certified by card check before the employers have a chance to object — effectively rendering the certification and the negotiating deadline faits accomplis.

That’s not quite true, however. The law allows anyone to file objections within five days of certification. After that, any certification can be revoked if the employers’ objections are later upheld at a hearing, and any mandated contract can be invalidated. Indeed, Wonderful filed its objections in time, citing the workers’ declarations; an ALRB hearing on its objections has been underway for weeks.

What appears especially to irk Wonderful is that the board has twice rejected its motions to suspend, or stay, the certification and negotiation procedure until after it rules on the company’s objections. The board responded that the law doesn’t provide for such a stay.

The company’s lawsuit thus amounts to an end run around the law. Gould is skeptical that Wonderful’s constitutionality claims will win much favor from California judges, but the case may be aimed at the notoriously anti-union U.S. Supreme Court majority.

“This Supreme Court has indicated that they want to reverse much of what was done in the 1930s,” a high-water mark for progressive labor and public interest laws, he said. In its lawsuit, Wonderful “has thrown buckets of paint against the wall in the hope that something will stick. Maybe they’ll be right on some of it.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.