At Whisper’s news-gathering operation, data collection comes under siege

- Share via

Can an app that people anonymously share confessions on, some of which become fodder for news stories, protect the users’ identities?

That’s the issue surrounding Whisper this week.

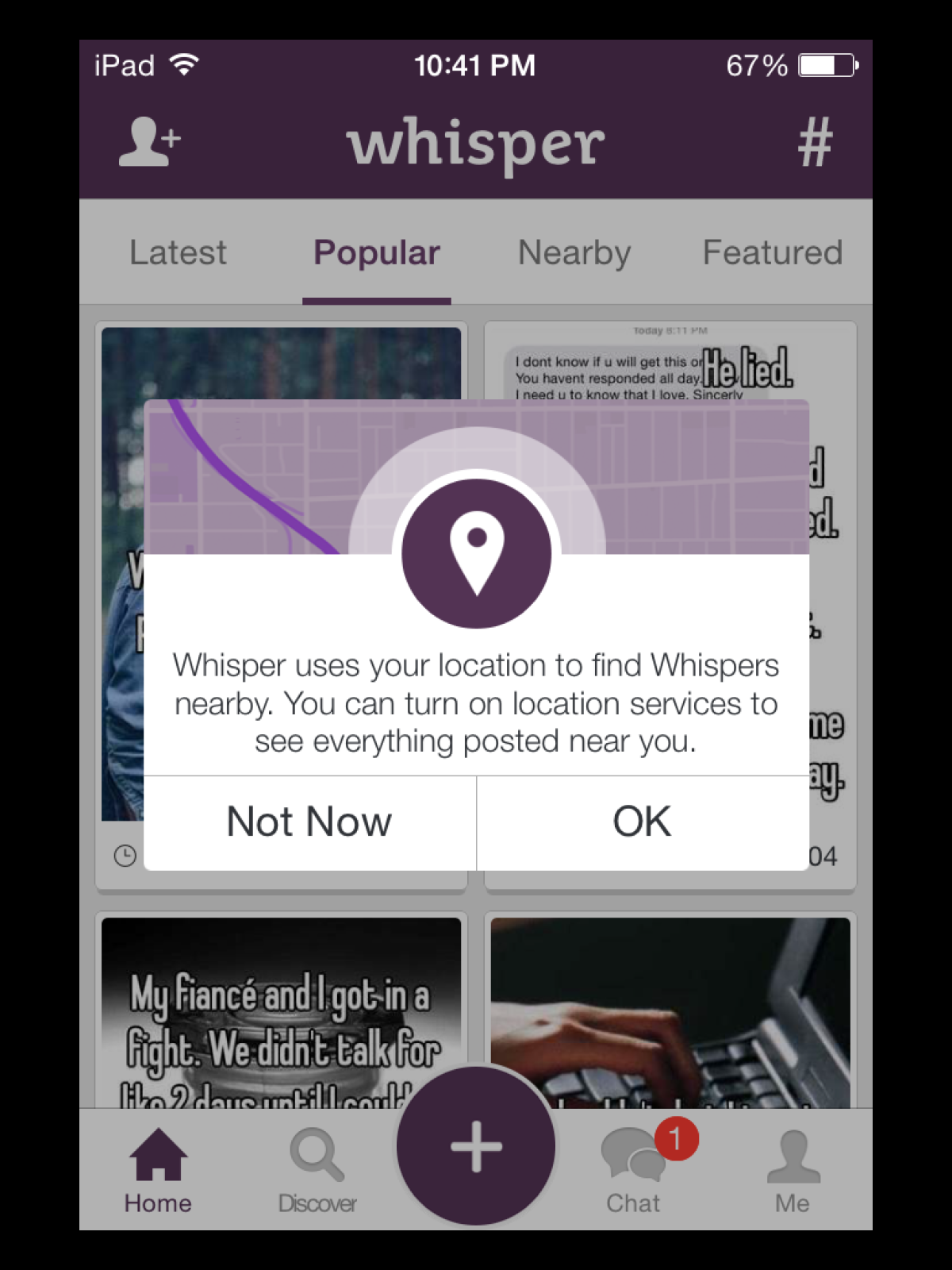

When opening the anonymous message board app Whisper on an iOS device for the first time, users are twice prompted to allow the Los Angeles start-up to determine their pinpoint location so they can view posts shared by people nearby.

But the Guardian reported Thursday that Whisper collects IP addresses and therefore continues to generally track even the thin slice of users who don’t consent to sharing location data. Monitoring IP addresses is common for online services. Whisper uses the data to defend against spam, deduce time zones for deciding when to send push alerts and personalize content, the company’s chief technology officer said.

The problem is Whisper does collect the unique code of a user’s mobile device. That allows Whisper to build a portrait of who’s using the app on that phone or tablet by tracking their interactions with the app. Those portraits could offer enough clues to come up with a real name based off public records.

Whisper was launched two years ago as a platform for people to express themselves without having to worry about tailoring messages to cultivate followers and likes or exude coolness. With $60 million in venture capital funding and about 70 employees, Whisper has a lot to deliver on.

But the media backlash against Whisper highlights the unique set of privacy challenges it faces as a media operation – a content creator – as opposed to simply a social network like Facebook or Twitter. Rather than being a platform where user data are tracked to deliver creepy, targeted advertising, Whisper for now has sought to mine user data to create revealing, sexy content.

“Whatever story you have in mind, you can improve on it by reaching out to people on Whisper” was the message of Neetzan Zimmerman, Whisper’s editor-in-chief, to the media during an interview at the end of August.

Speaking on a patio at Whisper’s mansion-turned-office off Venice Beach, Zimmerman said he had just moved to Los Angeles to be closer to a team of employees who search for trends and news by monitoring the 30 new Whisper posts each second around the clock. Location data are key to vetting users and identifying trends.

His editorial team collects posts around a topic they’ve noticed or decided to dig into, like “14 Things Your Roommate Is Really Doing After You Leave.” They’ve also uncovered more serious items such as soldiers moonlighting as escorts or a student being dismissed from a parochial school because she was lesbian.

People -- mostly college-age women -- are willing to share these “secrets” on a public forum because they know fellow users can’t identify them, Whisper says. The company used to charge users $5.99 a month to initiate private conversations with others on the app, but now it doesn’t collect details like names or email addresses. Half of users share, and 95% of posts receive engagement from others.

Whisper pitches hundreds of story ideas each week to more than 75 media organizations, including BroBible, Total Frat Move, Mashable and Buzzfeed.

This summer, Whisper decided to start posting ideas onto its website that media didn’t use.

“You don’t want to take content that we think is ready for prime time and throw it away,” Zimmerman said, calling the website a “safety net for runoff content.”

Media also can make requests for posts on a certain topic, and Zimmerman said turn-around time could be as quick as 30 minutes. The Guardian used Whisper to identify illegal immigrants once, Zimmerman said.

His team vets posts by noting whether the user’s location correlates with the claim made in the post, looking at the user’s previous posts and private-messaging the user to see if they would like to speak to the media. The same tactics could be used by law enforcement to identify users, and Whisper hands over data to authorities about two or three times per week, Chief Executive Michael Heyward said recently at the Vator.tv’s Splash LA conference.

Reporters could do all of this on their own without Whisper’s help, which is part of why Heyward said there’s no “ulterior motive” around making money off the curated content. The benefit is stories lead to more people trying out Whisper, and “seeing or thinking about an idea differently,” Heyward said while sitting on one of the purple couches at Whisper’s office.

As for generating revenue, Whisper has been running experiments. Each post on Whisper is backed by an image that fits the topic. Licensing those images is one of the company’s biggest expenses. (The largest expense is 130 content moderators in Manila contracted through TaskUs who flag lewd or abusive content.) But Whisper has toyed with the idea of suggesting images from advertisers when users are about to post on a certain topic. Developing a tool where companies could pay to see what people are saying about their product is another tool that’s been considered, Heyward said.

Whisper’s data collection is far from egregious, said Ben Zhao, a computer science professor at UC Santa Barbara who began studying Whisper at the beginning of the year and met with the company as recently as Tuesday.

“What they do is nothing compared to what we deal with in daily life in privacy challenges,” Zhao said by phone Thursday night. “The perspective they take on how to protect users is more than I’ve seen from other companies I’ve worked with, and that’s including LinkedIn, Google, Zynga and Yelp.”

Zhao’s study examined how anonymity meant users formed weak relationships on Whisper, which meant they had less incentive to stick with the service compared with a friends-based online network. He said Whisper’s story-creating operation counteracts the issue by giving people a reason to feel part of a larger group or trend.

Zhao reached out to Whisper in the late spring after his research team uncovered a security flaw that allowed the exact location of a Whisper poster to be identified despite the random error the company normally inserts to location information. Whisper fixed the issue. And as Zhao now seeks to collaborate directly with Whisper, executives have been insistent on not revealing any information that puts users at-risk of being identified, he said.

“They strike me as people who care about user privacy,” Zhao said. “What they say and how they act has been pretty consistent.”

Nicco Mele, who consults businesses on dealing with social and technology changes, said that Whisper’s data collection practices are not a surprise in today’s tech environment.

“What we haven’t come to grips with is outside that world, what are the acceptable norms and limits?” he said. “Those are the questions for our culture.”

Chat with me on Twitter @peard33