News Analysis: California’s Legislature tackled big issues in 2019. Bigger fights might be coming

Sixteen weeks will pass between the first and second acts of the California Legislature’s two-year session, an intermission that began Saturday and is often seen as a chance to switch gears from one set of topics to another.

But this time, the second year could be consumed by battles left over from the first.

It’s not likely to be because Democrats in the state Senate and Assembly picked too many fights in 2019, but rather ones that provoked strong reactions, embracing a panoply of far-reaching measures affecting the state’s economy and its environment as well as the rights of Californians at home, school and work.

“We have sent the governor a number of bills that will have a lasting impact on California and, in some cases, were a long time coming,” Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) said Saturday.

More than 2,600 proposed laws were introduced in the Legislature this year, a roughly 20% increase from 2018. Most passed or failed with little public fanfare. Those that make up the $215-billion state budget that Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law in June rely on the continuation of a six-year run of strong tax revenues, used to restore or expand public services slashed during the last recession.

The abundance of dollars has changed the contours of governing in Sacramento. So, too, has the abundance of Democrats.

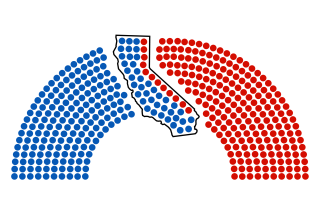

Following last year’s elections, a series of special runoffs to fill legislative vacancies and even the surprise party switch of a Republican legislator in January, there are now 29 Democrats in the Senate and 61 in the Assembly. Most bills need only 21 votes in the Senate and 41 votes in the Assembly to pass. Translation: Even with some ideological differences among their ranks, there are more than enough Democrats for passage of a liberal agenda addressing issues of race, wealth and opportunity.

One of the most emotional debates centered on the use of force by law enforcement. Two years in the making and prompted by the deaths of young African American men in officer-involved shootings, Assembly Bill 392 will narrow the circumstances in which officers can legally use deadly force. Its enactment marks a major political defeat for powerful law enforcement groups, though some far-reaching provisions were scaled back. Activists may continue the fight into next year, though many agreed that AB 392 marked a decisive turning point.

“This will make a difference not only in California, but we know it will make a difference around the world,” Assemblywoman Shirley Weber (D-San Diego) said at a bill signing event last month.

Few topics were as ubiquitous in Sacramento this year as the state’s affordable housing crisis. Legislators from the suburbs scuttled a bill to increase housing density in their communities. And last week, lawmakers celebrated passage of a new 10-year statewide cap on rent increases. The rent limitation plan was criticized by activist Michael Weinstein, president of the well-funded AIDS Healthcare Foundation, for not doing more. His group spent $25 million on an unsuccessful rent control ballot measure in 2018 and has already drafted a do-over effort for 2020.

Broad bipartisanship was unsurprisingly rare. But there was a notable exception in legislation to push back at high-dollar college athletics. Senate Bill 206, lauded by Democrats and Republicans alike, would give college athletes the right to earn money for use of their name, image or likeness. The bill is now on Newsom’s desk, and National Collegiate Athletic Assn. officials have threatened it could result in California teams being barred from postseason tournament play.

Other interest groups were more successful. Efforts to regulate sugary sodas fizzled as the beverage industry succeeded in dividing Democrats on the issue. And some fights failed to materialize at all: What was expected to be a serious effort to retool 2018‘s landmark consumer privacy law — which takes effect in January and will grant people in California new rights to control the information that businesses gather about them and sell — instead resulted in only a handful of narrowly focused tweaks.

The most visible and far-reaching battle of the year was over Assembly Bill 5, a pugnacious effort to ensure that a million or more California workers would be added to the ranks of those who qualify as employees of a business. The subject of intense negotiations, the legislation tested the relationship between Democrats and organized labor.

The battle began in the courts, not the Legislature. Last year, the California Supreme Court placed strict limits on when a business could classify a worker as an independent contractor — AB 5 was an effort to help clarify that ruling.

But the debate quickly became one of subtraction. Liberal lawmakers, who wanted AB 5 to guarantee broad worker protections, had to keep narrowing the bill to ensure passage. One after another, industries asked to be exempted from its limits on hiring independent contractors. The list of jobs given special treatment in the final version of AB 5 is both a testament to effective lobbying and a sign of the complexity of the 21st century workplace.

It’s expected that requests for industry exemptions will continue into next year, most notably by powerful technology companies. Supporters of AB 5 had sought to focus public attention on helping low-wage workers in the service industry but found the spotlight frequently stolen by ride-hailing companies Uber and Lyft. As barons of the emerging gig economy, the companies chafed at the idea that their drivers be considered company employees.

Tony West, Uber’s chief legal officer, went so far as to tell reporters last week that the rules for determining whether a worker is an employee or a contractor under AB 5 might not affect the company because legal rulings “have found that drivers’ work is outside the usual course of Uber’s business” and that Uber is simply “a technology platform.”

Not that the companies are content to leave it there. Uber, Lyft and food delivery service DoorDash are threatening to take the fight to voters, putting a combined $90 million into a political committee to craft, qualify and promote a ballot measure that would seek to preserve the status quo for their business models. The result could be one of California’s most expensive election showdowns ever — and could force labor unions to divert money from a high-profile ballot measure to exclude business properties from the low-tax protections of Proposition 13.

Democratic lawmakers are likely to feel pressure to deal with AB 5’s aftermath next year. Gov. Gavin Newsom, with friends and political donors in the tech industry, could be a key intermediary. That is, if other issues don’t fracture his relationship with lawmakers.

Things seem rocky at the moment, after the governor said Saturday that he will veto a priority bill of Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins (D-San Diego). Envisioned as an insurance policy for California should federal environmental protections be scrapped by President Trump, the legislation has left the two powerful Democrats at odds.

Other disagreements have emerged. Last week, lawmakers refused to advance Newsom’s effort to create state-level “opportunity zones,” tax breaks for the wealthy who invest in certain housing and green energy projects.

And many Democrats were frustrated by the governor’s zigs and zags on the bill to impose new oversight of medical vaccine exemptions for California school children. Vaccine critics protested outside the Capitol, blocked the building’s entrances, threatened legislators online and in person and, in the last hours of the final legislative day, one protester dropped what appeared to be blood from the Senate visitors gallery onto lawmakers seated below.

The final legislation included last-minute changes demanded by Newsom. Democratic leaders publicly expressed surprise at his actions, while others quietly suggested — while asking for anonymity to speak freely about the matter — that the governor might have inadvertently helped stoke a fire that will keep going long after the new laws take effect.

Fights that last more than a single legislative year aren’t unheard of in Sacramento. But lawmakers could be saddled with so many extended quarrels next year that their work will be more reactive than proactive. To top it off, 2020 is a campaign year and the primary election comes just eight weeks after the two houses reconvene — just the kind of swirling politics in which consensus can be hard to find.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.