It started with a stick — that much everybody can agree on.

A Korean stock boy wielded the stick at a black patron inside a Leimert Park liquor store late on a Sunday afternoon. In some tellings, the customer was rudely chased away for being short a nickel — another instance of the Korean-owned store mistreating the surrounding African American community. In others, the man was drunk and making his third booze run of the day, and the employee denied him service, as required by law.

The incident in late 2017 pitted the store’s longtime elderly Korean shopkeeper against a band of black activists who voiced familiar complaints about outsiders taking advantage of the scarcity of retail options in South L.A. It snowballed into a months-long boycott and protests and unnerved the neighborhood, the Korean community and a city that keenly remembers how similar tensions a quarter-century ago culminated with Los Angeles up in flames.

In time, one party would be driven out of town and the other would claim victory, with city and community officials scrambling to draw up a plan to prevent such tensions in the future.

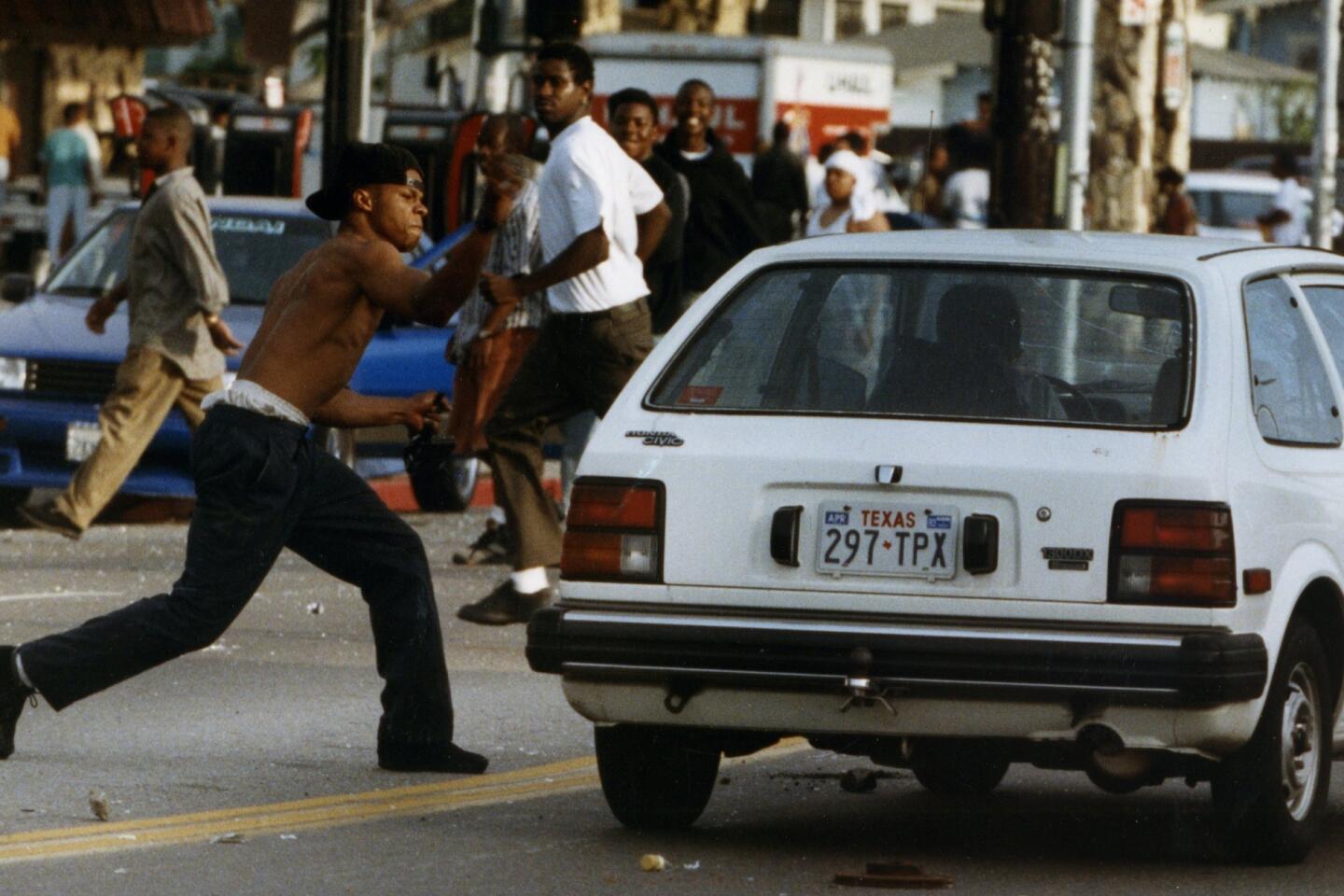

And to everyone involved, it was a reminder that the embers of the 1992 L.A. riots still smolder in communities where economic disparities and racial and cultural misunderstandings never went away.

The protesters

A half-dozen members of the Africa Town Coalition were holding their weekly food bank in Leimert Park, passing out meals and produce, when someone ran over and told them about the skirmish at Hubert’s Liquor.

They were regulars in the area, chanting black empowerment slogans and soliciting donations for food and school supply giveaways. Primarily middle-aged men, they belonged to the generation that came of age in Los Angeles during the collective ire of 1992, with the political angst but without the organizational prowess or scale of the Black Lives Matter movement.

For years, they had protested and boycotted businesses they believed had disrespected the community: a Walmart, a Boost Mobile, a Wienerschnitzel. When they heard about Hubert’s, they kicked into action and announced a “grand closing” of the store. They made signs — “Our $$s count. Respect Black Power” — waved the black nationalist flag and brought out the bullhorn, blocking customers from entering the store.

The protests tapped into long-held complaints about Hubert’s — the prices a dollar or two higher than at big-box stores, the short treatment from employees who didn’t seem to live in or care about the neighborhood, the row of photos taped on the bulletproof glass of suspected shoplifters. They didn’t know much about the owner, a diminutive woman who spoke faltering English, but it almost didn’t matter. To them, she was yet another outsider profiting off the neighborhood.

“They would add 5 cents more than necessary. For a lot of people, 5 cents is a big deal,” said Eschelle Washington, 38.

The Africa Town Coalition led a months-long protest of a Korean-owned liquor store in Leimert Park.

Protests and boycotts were tried and true methods for the group. William “Billion” Campbell, 49, staged his first protest in his 20s when a convenience store clerk yelled at him and his cousin for reading comic books without buying them. The clerk apologized after two days.

“We have the right to hold them accountable and choke off their finances,” said Kevin Wharton Price, one of the group’s leaders. “Irregardless of how people view our methods, our methodology is sound and successful.”

Hubert’s is in the heart of Leimert Park, one of Los Angeles’ last remaining historically black neighborhoods, an area the group was advocating to get renamed “Africa Town.” Protesters cried out to customers that the store “does not deserve the black and the brown dollars.” At one heated demonstration, Price and Campbell were briefly detained but not charged, and returned the next day to protest.

After weeks, when they felt their complaints were falling on deaf ears, they took the protest to Koreatown. The signs they carried didn’t mince words:

“No More Korean Merchant Parasites.”

The owner

It almost felt like fate that Soon Yoon had ended up in Leimert Park.

She had arrived in the U.S. with little to her name. She first worked at a gas station, then sold tamales and menudo in Canoga Park before she saved up enough to buy a liquor store in East L.A. When her husband left her for a younger woman, the store became a lifeline for Yoon and her two children.

During the L.A. riots, dozens of Korean-owned liquor stores were burned to the ground. By then a single mother in her 50s, Yoon planned to move on to something safer, maybe a coin laundry, and sold her store.

But one day she missed her normal exit off the 10 Freeway and somehow ended up in Leimert Park. She saw a busy liquor store for sale and soon bought it with a Small Business Administration loan.

For two decades, Yoon said, she thought she had a good relationship with the community. Save for some kids who would run out with a can of this or that a couple times a year, she had little trouble.

Her prices weren’t cheap, but an extra 2% or 3% markup was a business decision many shopkeepers made to take advantage of the lack of competition and compensate for what they believed was the risk of doing business in poorer, higher-crime areas.

“People think we’re raking it in, but they don’t see the 10 to 15 hours a day we put in, the loans we took out and the hard work we do,” said Mike Kim, president of the Southern California Korean American Grocers Assn. “They only think of the money we take away.”

Yoon had regulars with whom she exchanged warm greetings, who would come in for their morning paper or a snack after performances at a nearby theater let out. Now and then she paid a neighborhood guy down on his luck to sweep her parking lot. One man called her “mama-san,” and she would come out from behind the counter to give him a hug. Through the area merchants association, she donated to programs at nearby Crenshaw High.

The man who was chased out of the store with the stick also was a regular, the neighborhood drunk whose poison of choice is beer, Yoon said. She was watching through a security camera from the back when the trouble started.

When Yoon came out front to see what was going on, one of the women who took issue with the stock boy’s behavior threw water at her. A handful of protesters returned the next day with their signs and bullhorns, and again the day after that.

What started with complaints about one man’s mistreatment evolved into a litany of grievances, blaming all of the area’s social ills on the store and the liquor it sells.

The protests continued for weeks, then months. Police officers repeatedly came by to keep the crowd from getting out of hand, but said they couldn’t stop the group from rallying on public streets.

By December 2017, after months of on-and-off protests and lists of demands, Yoon’s daughter, concerned for her 79-year-old mother, began imploring her to leave it all behind.

The mediators

Alarmed by the protests, a store employee called the Korean American Federation, a community group that serves and represents first-generation, non-English-speaking immigrants.

Emile Mack, the federation’s vice president and a retired Los Angeles Fire Department official, said he could see the dispute from both perspectives. An adoptee from South Korea raised by black parents in South L.A., he grew up going to a corner liquor store a lot like Hubert’s for chips and soda in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Using his connections, he assembled a group to talk out the situation — representatives from the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, mayor’s office, City Council and Assembly. The group began meeting at a church and later at City Hall, going over demands from the protesters.

“The people that are actually in the community don’t have much better understanding or relationship than they did back in ’92.”

— Emile Mack, Korean American Federation of Los Angeles

Mack realized the situation at Hubert’s was a sign that, however much leaders of the black and Korean communities were holding joint events and posing for photo ops, among many Angelenos, stereotypes and misunderstandings persisted.

“The people that are actually in the community don’t have much better understanding or relationship than they did back in ’92,” he said. “‘Koreans, they’re just here taking our money. African Americans come in and they steal from us.’ … Basic things you could’ve heard 25 years ago, still being thought by most people in the community.”

Back then, nearly half the liquor stores in South L.A. were owned by Korean immigrants drawn by cheap rent, the minimal English required and a stock that doesn’t go bad. They set up shop in neighborhoods they didn’t understand at a time when crime was at an all-time high, police presence was heightened and black communities felt under siege.

Tensions rose in 1991 when a 15-year-old girl, Latasha Harlins, was shot in the back of her head by a Korean shopkeeper who suspected her of shoplifting. The hostility turned to rage when Soon Ja Du, convicted of manslaughter, was sentenced to probation. When South L.A. erupted in riots after the Rodney King verdict the following year, more than 2,300 Korean-owned businesses were looted and burned down.

In many ways, the Korean-owned liquor stores that still dot South L.A. today are a snapshot from the early 1990s. The majority of the owners are still first-generation immigrants whose children have gone on to more lucrative professions. Most of the customers also remain economically disenfranchised — if not worse off — compared with the rest of the city.

To Kirkpatrick Tyler, the mayor’s field representative for South L.A., it seemed as if everyone involved in the Hubert’s dispute simply wanted to be heard and acknowledged. He tried to act as a translator of sorts, “listening to people and putting what they’re saying in a palatable format that other people can understand.”

“It’s an uncomfortable space,” he said. “It’s about how do we make the decision, ‘Let’s stay in this space and talk to each other.’”

After spending hours with the protesters and speaking extensively with Yoon, the owner, Mack drafted a response to the Africa Town Coalition’s demands.

Yoon offered to participate in cultural sensitivity training and assist with local substance abuse programs; she agreed to offer more than just liquor and to make a monthly donation to the coalition’s food program. Mack noted that Yoon already had been sponsoring nearby youth programs and that she had previously employed a black clerk for eight years until he retired, and had been trying to hire others since. Yoon had already removed the photos of alleged shoplifters.

In December 2017, as Mack and the protesters were going back and forth about what changes should be made at the store, Yoon quietly sold the business to another Korean owner. Mack said she felt she was being portrayed in an unfairly negative light.

“It was really troubling her obviously,” he said. “It was just getting to be too much.”

Yoon later said that she felt pressured to sell for far less than what Hubert’s was worth. Some of her regulars, she added, implored her to stay, offering to call the police on the protesters on her behalf. She believes it was outsiders, not the community, who pushed her out.

”I never lost the neighborhood’s heart,” she said.

The aftermath

The protests continued for about a month after the ownership change, but eventually faded away. Since then, Hubert’s has become a symbol of both progress and stagnation.

Simon Choi, the new owner, lowered prices, cleaned up the store’s appearance and began stocking more fresh produce. He holds barbecues in the parking lot, donates beverages every week to Africa Town Coalition’s food giveaway for homeless people and donates $100 monthly to support the group’s activities. This fall, Choi also bought a new leaf blower for a neighborhood beautification project.

The Africa Town Coalition, the Korean American Federation and Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office have explored using lessons from what happened at Hubert’s elsewhere in Los Angeles. They talked of creating a “cultural competency” workshop for business owners to teach them communication skills and the historical context for specific communities, possibly devising a score that would be posted at each store like restaurant sanitation ratings.

But after several meetings, working groups and proposals, the effort has fizzled, with a new South L.A. representative for Garcetti’s office and the community groups moving on to other issues.

Mack said recently that until fundamental inequalities are improved, another situation like Hubert’s probably awaits in some other corner of Los Angeles.

“Unless there are changes that allow the smaller business to be acquired by the average person, it’s still going to be difficult,” he said. “I don’t think the changes have been made that make black ownership any more viable today than it was 25 years ago.”

This fall, there was one final piece of unfinished business from the battle over Hubert’s.

Kevin Wharton Price, one of the protest leaders, walked into a downtown courthouse in November wearing a faded Africa Town sweatshirt. He had come to address the 2-year-old warrant he had received after demonstrating at the store. The penalty: a $400 fine.

To Price, it was worth it for Leimert Park. Besides, he said, he plans to let it go to collections anyway.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.