California courts paralyzed by coronavirus, with justice hanging in balance

When he strode to the bench inside the Compton courthouse Friday morning, Superior Court Judge Michael J. Shultz was wearing two items more necessary than his pleated black robe: a pair of latex gloves and a face mask.

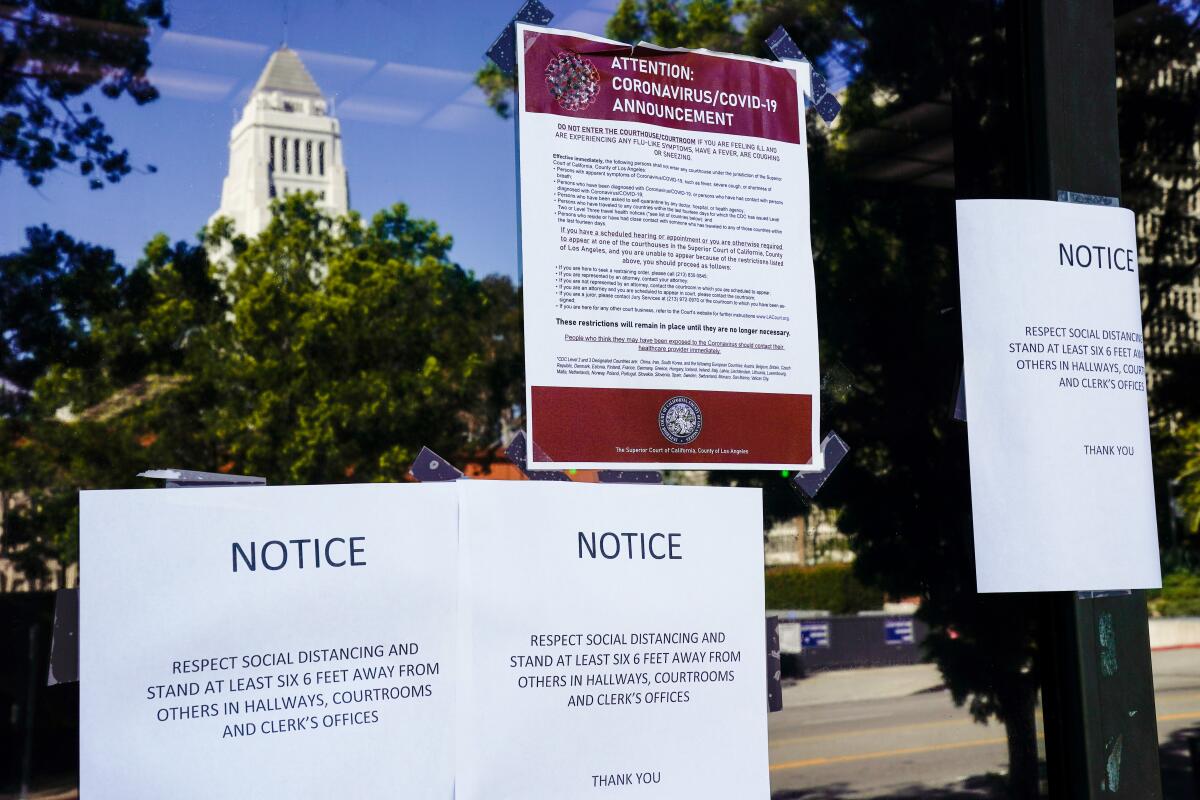

Miles north in downtown Los Angeles, caution tape had been placed over entire rows inside the criminal justice center’s notoriously hectic arraignment court to put as much distance as possible between those in the gallery.

Even the simplest of courthouse functions had to be altered. When an attorney asked to approach Superior Court Judge Emily Garcia Uhrig as she worked her way through more than 100 items on her calendar in a Van Nuys courtroom Friday, the judge seemed to eye the bench cautiously, taking stock of the risks of having others so close to her.

“Let’s go into the hallway,” Uhrig said, before leading the prosecutor and defense attorney out of the room.

While the coronavirus has paralyzed much of California, the criminal justice system does not have an off-switch. At a time when close quarters, hushed conversations and teeming crowds that are standard in L.A.’s courthouses could prove dangerous, law enforcement leaders are scrambling to figure out how to balance public safety and defendant rights. It’s a situation where even the most routine court proceedings pose the risk of spreading the virus.

In Los Angeles County, home to the nation’s busiest court system, judges returned to the bench Friday after a three-day hiatus. But with trials frozen for at least a month and law enforcement leaders trying to reduce the size of the prison population for fear of sparking a viral outbreak in the jails, the continuing public health crisis threatened to cause a lengthy case backlog and force police and prosecutors to drastically scale back enforcement for the time being.

“You’re going to look at possible mistrials … you’re going to look at defendants en masse asking to be released from custody,” said Laurie Levenson, a Loyola Law School professor and former federal prosecutor. “It’s unprecedented. You’re going to have to make some tough choices.”

PATCHWORK MEASURES

In Department 30, the downtown criminal justice center’s often packed arraignment court, a tub of Clorox wipes was open on the desk where defense attorneys normally sit.

Next door, Judge Jose I. Sandoval began the day’s proceedings by sentencing Tyimere Hollinsworth to three years probation after he pleaded no contest to a drug possession count. But citing the pandemic, Sandoval postponed his date to report to probation to June 1.

“Maybe you haven’t heard of it,” Sandoval told the defendant of the coronavirus outbreak. “You will hear a good deal about it when you are out.”

Conditions seemed to vary by location. In Van Nuys last week, deputies allowed only two people at a time to enter the security area and limited courtroom access to attorneys, staff and defendants. People who had come to support their relatives were escorted to adjacent closed courts that had been turned into waiting rooms. Signs hung near elevators advising that no more than four people should enter each car.

But Meredith Gallen, a deputy public defender and a board member for the union representing them, said she saw “incredibly long lines” outside the Compton courthouse Friday. Plastic trays in the security line were not cleaned after they were handled by court visitors, she said.

“We have not been provided supplies by any county agency,” she said. “People bring in their own personal wipes and hand sanitizer to clean up court areas.”

Concern about the virus and its impact on court functions seemed to explode in recent days, as the number of infected persons in the state climbed toward 1,000. (There were over 1,400 cases in the state as of Saturday night, March 21.)

On March 11, L.A. County’s Presiding Judge Kevin Brazile canceled several retirement parties and seminars, according to a copy of a memo reviewed by The Times. A week later, he ordered the county’s courthouses to be shuttered for three days and froze all trials for a month, limiting court functions to what he deemed essential matters — including proceedings such as arraignments and timely criminal preliminary hearings.

Across the state, a patchwork of measures have been taken to address the pandemic’s impact on criminal justice. San Diego’s courts will operate on an extremely limited basis through April 3. In Alameda County, courts are closed until April 7 except for certain proceedings, like arraignments and hearings regarding restraining orders.

Orange County announced it would close its courts for 10 days starting March 17, but an attempt to host some proceedings in a Santa Ana courthouse this week descended into “complete chaos” that led many lawyers to fear for their own health.

Leaders of the nine unions whose members work at L.A. County courthouses — including sheriff’s deputies, court interpreters and public defenders — have implored Brazile to add trained staff to screen courthouse visitors, provide soap to those in custody at courthouses, and allow bailiffs to limit courtrooms to 10 people.

“It is irresponsible to allow the courts to resume as if it is ‘business as usual’ during this critical worldwide pandemic,” said the letter to Brazile. “We need to take action now in order to effectively protect the nearly 20,000 professionals who interact in these public buildings each day.”

Ann Donlan, spokeswoman for Los Angeles Superior Court, said, “The Court is reviewing the letter.”

On Saturday, the California District Attorney’s Assn. sent a letter to the state Supreme Court asking for a uniform set of rules to be instituted statewide regarding court practices. The letter, written by Alameda County Dist. Atty. Nancy E. O’Malley, asked for the top court to determine what an “essential function” is, and to give local presiding judges authority to continue delaying trials if the health emergency persists.

CALCULATING RISKS

On average, records show, L.A. County prosecutors filed 10,350 cases per year from 2010 to 2018. That figure is likely to fall. The number of arrests recorded by Los Angeles police and sheriff’s deputies has already fallen during the outbreak.

There have been no reported outbreaks in the county’s jails or among district attorney’s employees and their relatives, officials have said. But three LAPD employees were sickened by the virus last week, and a downtown L.A. federal holding center had to be cleared out and cleaned earlier this week after a prisoner began displaying symptoms of the virus, according to two people with knowledge of the situation who spoke on condition of anonymity.

A spokesman for the U.S. Marshal’s Service, which controls the federal lockup, did not provide additional information.

The district attorney’s office, sheriff’s department and public defender’s office are planning to review about 2,000 cases involving defendants currently in the county’s jails to see if they can be safely released ahead of trial due to the health crisis.

Additionally, Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey has asked prosecutors to consider a defendant’s risk of exposure to the virus as a factor when arguing for a bail amount to be set. In an interview, Lacey said her office will prioritize prosecutions involving violent felons.

“It’s inevitable that some cases are going to be lost. They’re going to be dismissed, not filed, because we’re going to have to prioritize, right?” Lacey asked. “You’ll see prosecutors looking to settle cases more because we just can’t accept this volume that we’re looking at … but I think the important cases won’t be lost. They’ll be adjudicated, the serious cases.”

‘STRANGE TIMES’

On the 9th floor of the downtown courthouse Friday, Judge George Lomeli sighed, “strange times,” as he put on his robe and took the bench.

Anastacio Hernandez, 62, was shackled at the waist for what was supposed to be a sentencing hearing. Hernandez was convicted by a jury in January of assault with a deadly weapon.

His public defender, Ruchi Gupta, asked the judge to release him pending sentencing citing his age and health issues.

“Since he’s in custody, he’s exposed ... he’s in the age group where he’s most likely to develop the virus,” Gupta said, noting that the social distancing measures that the public must undertake were not possible behind bars.

The prosecutor objected to any release, and the judge was unswayed by the public defender’s plea. He noted there were no coronavirus infection cases in custody, and that public safety still called for Hernandez to remain in jail.

“The court is not inclined to release,” Lomeli said.

Many of the cases called Friday were continued to dates as far out as mid-June. Lacey said it is near impossible to predict how severe of a backlog the county’s court system will suffer. A number of highly anticipated trials, including the prosecution of Robert Durst, have already been delayed.

Going forward, Lacey said, the virus will have to be a factor in nearly any filing decision or plea deal her prosecutors make.

“If it’s serious, if somebody’s getting hurt, if it looks like something devastating is happening … then that’s going to get worked,” Lacey continued. “But if it’s something that can wait, it will.”

Some defendants downtown feared their health might come down to a judge’s discretion.

Robert Gallo, 54, sat nervously, fiddling with his glasses and wiping sweat off his brow. Gallo, who said he is homeless, was facing charges of welfare fraud. He denied the charges, and was terrified that the new accusation would trigger a probation violation and jail time.

Gallo did not have an attorney. When he was eventually approached by a public defender, she introduced herself from several feet away, wearing purple latex gloves.

“I hope you understand I have to keep my distance from you,” the defense attorney said.

Around 11 a.m., the judge called the case and asked Gallo to return on June 19. In the meantime, he was released on his own recognizance.

“Unbelievable,” Gallo said, relief washing over his face. “I can’t believe I’m going home.”

Times staff writer Nicole Santa Cruz contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.