Review: Nancy Pelosi dishes on chiding A.O.C. and using “Moscow Mitch” in a revealing new biography

On the Shelf

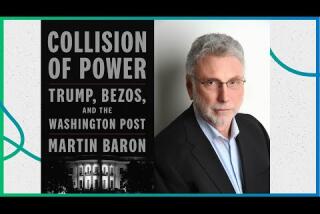

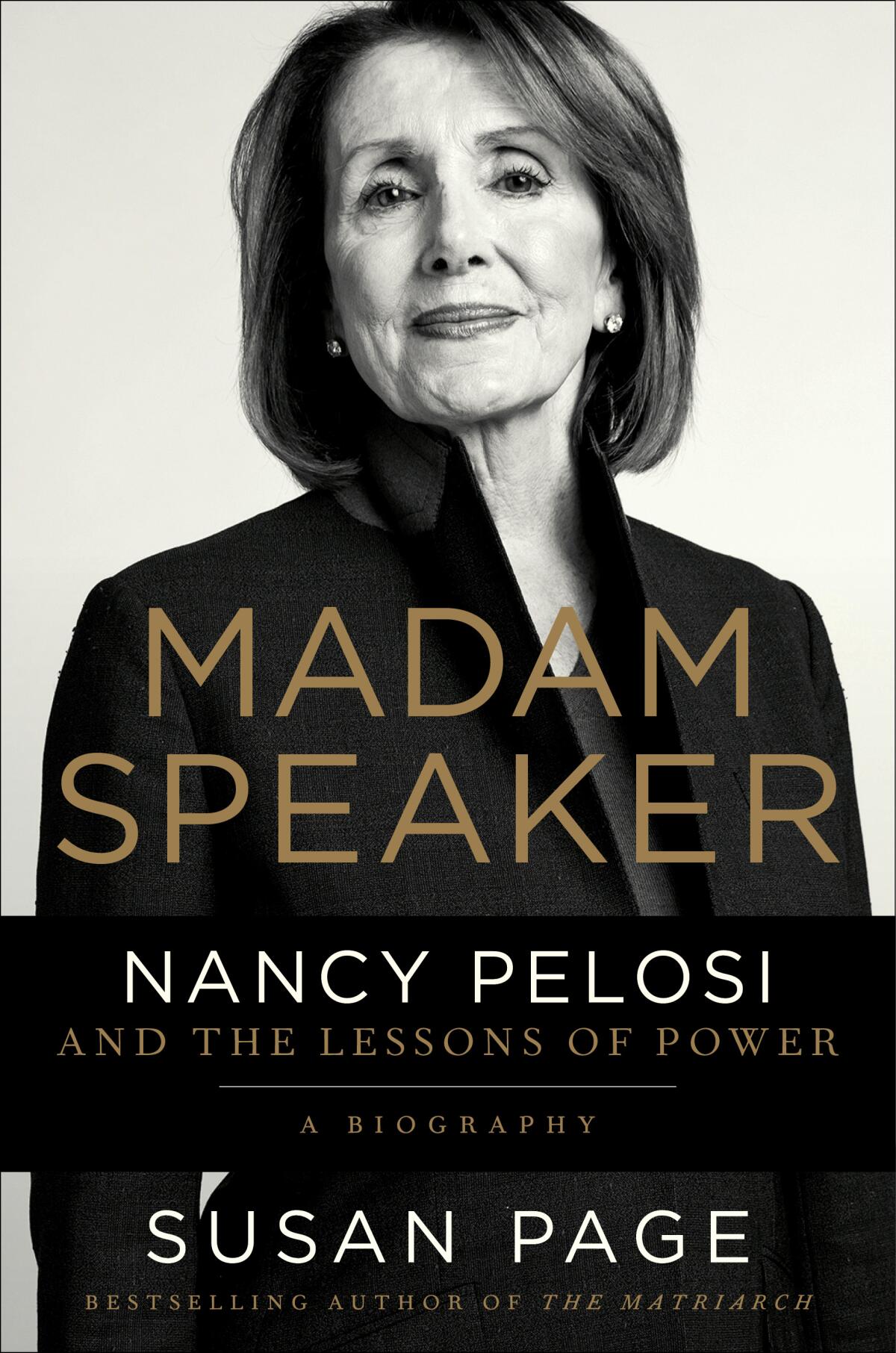

Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Lessons of Power

By Susan Page

Twelve: 448 pages, $33

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

It’s difficult to write a fresh-sounding biography of a woman who has been in Washington longer than some members of Congress have been alive.

But even longtime watchers of House Speaker Nancy Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) will learn something new about the most powerful woman in the country — and how she got that way — from USA Today Washington Bureau Chief Susan Page’s new biography, “Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Lessons of Power,” out this week.

Page notes the potential pitfalls in exploring such a known quantity, noting Pelosi’s tendency to recite the same quotes by Thomas Paine, Abraham Lincoln, even Ronald Reagan; her ability to stay relentlessly on message; and her unwillingness to dish to reporters. Some well-trod anecdotes make their way into the book, but Page’s unprecedented access to the two-time speaker — 10 conversations over two years and interviews with 150 of Pelosi’s family members, friends and confidants — opens windows into Pelosi’s working style and relationship with colleagues that few other profiles or biographies can match.

Page uncovered details from Pelosi’s life that even surprised the speaker, such as the patent her mother applied for in the 1940s after inventing a machine to give steam facials and handwritten notes toward a memoir by Pelosi’s beloved late friend, Rep. John Murtha (D-Penn.).

There are juicy tidbits of more topical interest, especially in chapters toward the end of the book: how Pelosi canceled plans to retire because Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, as well as the real reason she tore up her copy of Trump’s 2020 State of the Union speech. (Pelosi claims it started with a missing pen. I won’t ruin it.)

Nancy Pelosi is winning her showdown with President Trump for one simple reason: She knows how to do her job better than he knows how to do his.

Then there are Pelosi’s frank comments about colleagues, unusual even for a powerful veteran already well-known for her candor. Pressed by Page on how she felt about the “Squad” of four newly elected progressives, including New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, in a 2019 interview, Pelosi appeared to swipe at their social media savvy.

“Some people come here, as [former House Appropriations Chair] Dave Obey would have said, to pose for holy pictures,” Pelosi said. Then, she raised her pitch to mimic a child, “See how perfect I am and how pure?”

“OK, there’s the group that’s going to go pose for holy pictures,” continued Pelosi. “Now let’s legislate over here.”

The interview came amid a furor over comments from Pelosi minimizing the squad’s power in Washington, reminding journalists that each member only has a single vote where it actually counts, and a subsequent Twitter attack on moderate members by Ocasio-Cortez’s then-chief of staff. Publicly, she and Ocasio-Cortez were downplaying the exchange.

“They’ll understand when they have something they want to pass,” Pelosi told Page. “If you have something that you want to pass, you’re better off not having your chief of staff send out a tweet in the manner in which that was sent out. Totally inappropriate.”

Page also details for the first time the disagreement between Pelosi and then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) about whether to allow the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to lie in state in the Capitol Rotunda following her death last year.

Ginsburg did become the first woman to lie in state at the Capitol, but she was in Statuary Hall on the House side of the building after McConnell said there was no precedent for having a justice recognized by lying in the rotunda.

Page adds that Pelosi calls McConnell “Moscow Mitch” because she knows it gets under his skin.

“Mitch McConnell is not a force for good in our country,” Pelosi told Page. “He is an enabler of some of the worst stuff, and an instigator of some of it on his own.”

Pelosi has been candid in the past about her scuttled plans to retire, but Page teased out new details, including a list of what Pelosi was looking for in a successor: someone who would unite the Democratic Caucus; would be able to negotiate with the White House and the Senate regardless of party control; and could motivate grassroots activists and raise money from big donors. While these are hardly groundbreaking insights, Pelosi normally brushes aside questions of succession in public.

The House speaker isn’t going anywhere, yet. But that’s not stopping her would-be successors.

But Page spends the majority of her book on earlier days, providing fresh details of Pelosi’s childhood in the public eye as the only daughter of Baltimore mayor Thomas D’Alesandro, including a lengthy section on how the family survived a potentially career-ending scandal — the trial and acquittal of Pelosi’s brother Roosie D’Alesandro on charges of raping a 13-year-old girl.

And she dives deep into the transformative moments in Pelosi’s early political career that are so well known a biographer might be tempted to skim over them.

That includes Pelosi mocking herself years later for trying to explain to a staffer with an idea for a quilt eulogizing AIDS victims that “nobody sews.” The AIDS Memorial Quilt became the largest community art project in the world, with 50,000 panels commemorating 105,000 people. Page recounts how a chastened Pelosi, in one of her first major battles in Washington, then maneuvered the National Park Service into permitting the massive quilt to be displayed on the National Mall during the 1987 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights — promising to have volunteers “fluff” the quilt every 20 minutes so the grass underneath wouldn’t die. (It did.)

Page also discovered handwritten pages dictated in 2008 by Murtha, archived at the University of Pittsburgh, explaining why he provided pivotal support during Pelosi’s first leadership bid. Murtha was crucial in convincing “some of the old guys” who were hesitant to pick a woman as speaker and supported her over Rep. Steny Hoyer, still her No. 2 today. His notes, intended for a never-written memoir, go all the way back to his first meeting with Pelosi.

“More liberal than I but she has ability to get things done and she’s given a tremendous service to our Cong. & country,” Murtha wrote. She has as “good a political mind as I have ever seen,” he noted elsewhere. “Able to come to a practical solution. I appreciate that more than anything else. Get something that can be passed.”

Pelosi was so pleased upon learning of the notes, Page recalls, that she asked to keep a copy.

Pelosi is well known on Capitol Hill for her ability to determine what a lawmaker’s underlying need is behind a situation and for knowing them and their districts better than they do themselves, but the kinds of minutiae that prove it are usually too granular to make their way into news articles. Page has the room, and in many places in the book, it’s the smallest, best-chosen details that tell the biggest stories about Pelosi as a master legislator.

Republicans capped state and local tax deductions in 2017. California Democrats aren’t joining their East Coast colleagues in insisting on a fix now.

For but one example, while whipping votes for the Affordable Care Act, President Obama invited undecided Indiana Democrat Joe Donnelly to the Oval Office to try to sway his vote. Donnelly left still undecided.

Pelosi, meanwhile, turned to Donnelly’s religious mentor, the Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, president emeritus of Notre Dame — a man Donnelly referred to as a second father — and asked Hesburgh to help her pass the bill by calling the congressman.

By the end of their phone call, Donnelly agreed to support the legislation.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.