Indie Focus: Sitting with the anxious comedy of ‘Shiva Baby’

Hello! I’m Mark Olsen. Welcome to another edition of your regular field guide to a world of Only Good Movies.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

What’s that saying, never meet your heroes? I personally have never found this to be true. This job has afforded me the opportunity to meet more than a few people I greatly admire, and I haven’t been let down yet.

I recently interviewed filmmaker and actor Albert Brooks about the 30th anniversary of his 1991 film “Defending Your Life,” released in a newly restored edition by the Criterion Collection. The film stars Brooks as a man who dies and finds himself struggling to navigate the bureaucracy of the afterlife when he meets a woman played with graceful ease by Meryl Streep.

Brooks spoke about the reason why he thinks people talk to him about “Defending Your Life” in particular more than any of his other films. As he said, “I think it’s the subject of fear and death. I’ve had people say that they showed it to people they thought were heading out of here, just to give some sort of meaning where they couldn’t find meaning. And I just think that when you get into those topics, you’re going to get much more emotion. If you talk about literally anything to do with dying and what that may mean, that’s something everybody thinks about. And especially since this isn’t religious, it’s more about standing up for yourself while you’re alive. I think a lot of people have that issue.”

For “The Envelope” podcast, I spoke to director Thomas Vinterberg and actor Mads Mikkelsen about their collaboration on “Another Round,” which earned two Oscar nominations. The story is about a group of Danish high school teachers who, in the midst of a mutual midlife crisis, begin an experimental program of controlled drinking. That quickly gets out of control.

As Vinterberg said, “To begin with, we just looked at world history, and we saw how many fantastic and great accomplishments have been done by people who were actually drunk. And we wanted to make a celebration of alcohol and that developed into a more ambitious project of making a film about the whole nature of alcohol, also the dark sides.

“And then in the process of writing, again we wanted to elevate this to be more than about just drinking. We wanted it to be about life and our humbleness.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

‘Shiva Baby’

Written and directed by Emma Seligman, “Shiva Baby” is a comedic pressure cooker about what happens when the compartmentalized portions of your life suddenly collide. College senior Danielle (Rachel Sennott) is forced by her parents to attend the shiva for an aunt she didn’t particularly know. Amid the endless small talk and prying questions about her uncertain future, she runs into both her ex-girlfriend and the sugar daddy she sleeps with for extra money. With a supporting cast that also includes Molly Gordon, Dianna Agron, Jackie Hoffman, Polly Draper and Fred Melamed, the film is playing at Laemmle’s virtual cinema.

For The Times, Gary Goldstein wrote, “Seligman leans too heavily on the Jewish tropes here, only partly mitigating what some may find offensive via her characters’ well-meaning, if suffocating, concern and the film’s amusing dollops of nervous energy. … Sure, there’s authenticity at work — who hasn’t known or at least met some of the broad-stroked folks seen here? But a shrewder, more measured approach might have made the film more accessible and engaging. As is, it largely plays like one of those semi-hip farces from the late 1960s or early ’70s — only with minivans and sexting.”

For Vulture, Helen Shaw wrote, “Which conventions Danielle should break, and which she shouldn’t, isn’t always clear. … For 70 minutes, Danielle is caught in a push me, pull you of wanting to be seen — despite depending on them financially, she wants her parents to stop treating her like a kid — and wanting to move through the room invisibly. Being a child is hellish, but the examples of the adults all around her seem even worse. You’re supposed to grow up … for this?”

For That Shelf, Manuel Betancourt wrote, “Sennott plays Danielle like a young woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, but her flashes of self-assuredness even in the face of constant humiliation are what make ‘Shiva Baby’ so entertaining. … Seligman’s seemingly free-wheeling script, whose rhythms really do make it feel almost like a literate verité film (“He’s married to a shiksa princess. Poor guy.”), goes a long way to making ‘Shiva Baby‘s’ approach to sex work, to queerness, to consent, and to the many ways they collide in Danielle’s life, feel organically woven into a character study you don’t ever want to end. (Though, trust us, you will breathe a sigh of relief when its intentionally interminable final scene comes to a close.)”

For rogerebert.com, Monica Castillo wrote, “Seligman bottles these inter-personal tensions and slowly simmers them to boil, escalating each situation by just the right amount until the film’s ultimate crescendo and final punchline. The result is a painfully funny comedy that feels both universally relatable in its depiction of awkward family dynamics and very specific to Danielle’s experience of watching her sex life collide with her religious community. ... It’s the kind of mental gymnastics and fake pleasantries one does to save face, like a pained smile to soothe over any disapproving raised eyebrows. Seligman captures these performative nuances with astute precision.”

‘This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection’

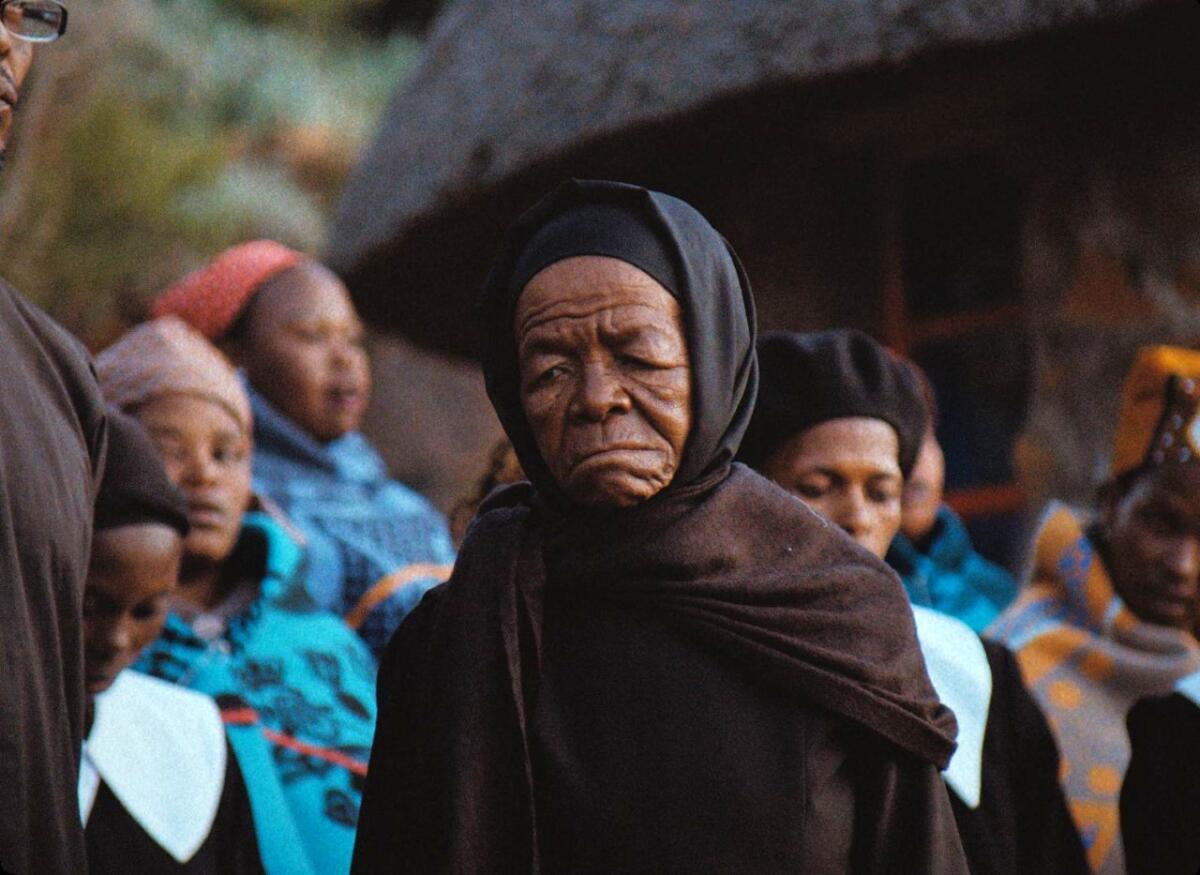

Directed by Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese, “This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection” was the first film submitted for the Oscars from the small African nation of Lesotho. Upon learning of the death of her son, her last living relative, an 80-year-old widow named Mantoa (Mary Twala Mhlongo) begins to make preparations for her own burial. But once she learns that her village is to be flooded for a dam project, she finds renewed energy defending her ancestral home. The film is playing at Laemmle’s virtual cinema.

For The Times, Robert Abele wrote, “It’s hard to imagine what ‘This Is Not a Burial’ would be, however, without the striking presence of veteran Soweto-born actress Twala Mhlongo, who some may remember from a memorable appearance in Beyonce’s ‘Black Is King’ and who died last year at the age of 80. Her Mantoa is quite the final portrayal, embodying one African woman’s lifetime of love and sorrows while articulating the story’s more ambitious themes of death and rebirth with persuasive force. Her lined face, frail but steady stature, and admirable doggedness are this movie’s relief map of human endurance.”

For the New York Times, Nicolas Rapold wrote, “Lesotho-born director Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese shoots his film as a kind of living legend, with a mix of warm-hued tableaus and hillside portraits in defiance. Mosese reaches for a knockout from the very first sequence, a narcotic pan across a hauntingly lit party scene that rests on the film’s narrator figure, playing a lesiba (a mouth-blown string instrument). Though the film cuts back to this mystery storyteller periodically, Mhlongo … carries the movie on her shoulders with an authoritative presence.”

For 812filmreview, Robert Daniels wrote that in the film, “unexplained events take place in the village. A home is burned down, a boy is killed. They appear to be the work of a vandal, or something more. Either way, the magical realism of the film turns upon loss: property, loved ones, traditions, and homelands. Throughout these tribulations, the 80-year old Mhlongo delivers an astounding performance, wrapped in a devastating minimalism that’s emblematic of a country that’s lost much while awaiting the promise of progress.”

‘Nina Wu’

Directed by Taiwanese filmmaker Midi Z, who cowrote the script with star Wu Ke-Xi, “Nina Wu,” combines a thriller with social issue drama. An actress in Taipei (Wu) struggles to make it through the humiliations and exploitations of what it takes to succeed, growing into herself along the way. The film is available via Laemmle’s virtual cinema and also on digital and VOD.

For The Times, Sarah-Tai Black wrote that Wu “is astonishing in her dexterity and ability to evoke the confrontational as certainly as the desolate. ‘They’re not only destroying my body but my soul,’ she repeats throughout ‘Nina Wu,’ a line from the film-within-a-film that serves a dual purpose here as an indictment expressed with such increasing urgency that it transfigures under the weight of its livedness. … Truth and delusion intermingle within this space, materializing not as spectacle or doubt, but rather as an embodied, if not literalized, study of the ways in which women attempt to intellectually and emotionally make sense of their experiences of exploitation.”

For the New York Times, Beatrice Loayza wrote, “It’s easy enough to slap the #MeToo label on ‘Nina Wu’ and call it a day. Yes, its titular heroine (a remarkable Wu Ke-Xi, also a co-writer) is an actress brutalized and exploited by a misogynist film industry, and the Taiwanese director, Midi Z, never pulls his punches. Yet this startlingly evocative, complex and confrontational new film is not interested in justice or didacticism.”

For Variety, Jessica Kiang wrote, “There are narrative avenues that are perhaps unnecessary and serve to complicate the tangle of real and unreal even more. … Still, it is unusual for an Asian title to centralize female desire, experience, and psychology to this degree, especially when it’s styled as a neo-noir, in which genre the female roles are traditionally largely decorative lures for the male protagonist to negotiate. ‘Nina Wu’ is a thrillingly complicated sort of corrective, living out the progressive ideal of giving the victim back her story, even when that story, told with lacerating self-criticism and a deep undercurrent of dismay, includes a great deal that falls far short of progressive ideals.”

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.