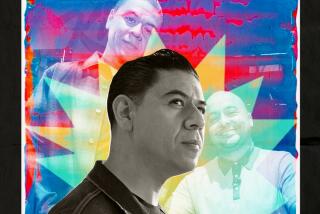

Sarah Silverman defends Dave Chappelle and humor that offends: ‘That’s comedy. You overstep’

When it comes to Tales of the Emmys, few are more bittersweet — or just plain sweet — than when an already canceled series is recognized with a nomination. It’s a reminder too that you can’t always judge a creative success in commercial terms.

“We were so tickled,” said Sarah Silverman, whose series, “I Love You, America,” was canceled by Hulu after its second season ended late last year but has been nominated for an Emmy in the variety sketch category. “It got canceled six months ago, so I’ve moved on a bit in my mind. But we had such a great time. We were sad when it got canceled.” (It was nominated for its first season as well.)

“Variety sketch” doesn’t adequately describe the show. (Or, for that matter, most of what else is nominated in the category, including “At Home With Amy Sedaris,” “Documentary Now!,” “Drunk History” and “Who Is America?” It fits “Saturday Night Live” well enough.) Though it’s hosted by a comedian and features appearances by Fred Armisen as Jesus, Will Ferrell as Socrates, Maya Rudolph as a French Statue of Liberty, and Sen. Cory Booker and Silverman ordering fast food and government programs at a drive-through, it’s also the expression of a worldview, a philosophy, a hope. And it’s a sort of adventure in which Silverman goes out to meet people with different worldviews, philosophies and hopes.

The show, whose 21 episodes are still available on Hulu, is full of ideas, kicked around for laughs, to serious ends. (A game of HORSE among clerics to determine which religion is the right one — with Silverman repping atheism — is an incidental study in ecumenism, as well as the theological universality of basketball.) And although the host’s own liberal politics are easily discernible throughout, the point, as reflected in its un-ironic title, was not to demonize the Other. Rather, it’s to make us look past the mutual incomprehension that turns us into tribes — and into the mirror while we’re at it.

You grew up in New Hampshire. How did that affect your understanding of different, possibly conflicting communities?

My sister Susie says it best — we thought being Jewish meant being a Democrat, because that’s how we were different from New Hampshire; there weren’t many of either. We weren’t raised really with a strong sense of Judaism, other than just being very aware that we were Jewish. It didn’t really become clear to me until I got older and looked back on it, but even growing up, all my friends’ parents would say, “Are you from New York?” and I’d go, “What’s New York? I’m from here!” ... And another thing, which probably helped in becoming a comedian, is being Jewish, I had an innate sense that I needed to make my friends’ parents feel safe and comfortable with me in their home.

When I was in seventh grade our family worked for the Jesse Jackson campaign and I had a … douchebag English teacher, and after Jesse Jackson called New York “Hymietown,” my teacher goes, “We work for the Jesse Jackson campaign, but I’m sure Sarah’s family doesn’t.” I remember even then thinking, “Actually, our whole family’s working for the Jesse Jackson campaign — and if you think he’s anti-Semitic, why are you working for the campaign?” It was very odd when I got disillusioned with grown-ups not knowing everything. But sometimes there’s relief in that, in that it kind of led the way to critical thinking. When that took hold it changed my whole life.

Did you experience overt anti-Semitism growing up?

I could say yes, but I would say no — in third grade I remember walking on the bus and kids throwing pennies and nickels at my feet. I didn’t understand why and then somebody said, “Oh, it’s because Jews are cheap.” And I was like, “Oh.” I didn’t really think anything of it. One of the kids who led the pack became my little third grade boyfriend weeks later. So did I encounter anti-Semitism? Yeah, I guess, technically. But so much hate is just ignorance. It was just kids learning stuff from their parents. I don’t think they had an ideology.

As a comic you deal in irony, but there’s also a strain of real sincerity in “I Love You, America.”

That was something that hit me when we were developing the show. I had all these earnest ambitions, and I thought, “If anything earnest isn’t sandwiched between super aggressive hard jokes or aggressively stupid silly humor — which is my favorite — then we should just [cancel] ourselves right now.” If I watched a show that was just the earnest part, I’d probably just be like, “... you.” I was so enwrapped in the earnest endeavor I forgot, “This must be served with very hard or very silly jokes.” And it was a good balance.

We did 21 episodes — I mean, it’s nothing. A show like that needs at-bats; it just got more and more honed and realized. It was unfortunate that we had to stop, because we were just figuring it out. I remember editing the very last episode, which I didn’t know would be the very last episode, but I knew it was the last episode of the season. I had this thing wash over me, like, “Oh, I get it now — we’re being too precious!” But that’s showbiz, baby! I liked having [the show], especially during these times. It was the happiest I had been, because it was a place to put everything. Now I’m just playing basketball so much more, because I’m in need of places to put my rage and just have human contact, even if it hurts.

Does rage improve your game?

Oh, it’s awesome. It’s not rage — the guys don’t see it. I’m laughing and talking [smack] and joking around. I play hard and I go inside. I mean, come on, my face is my fortune — I should be staying on the outside! But I’m crazy like that. I’m also so much older than everybody else; my body’s falling apart. And I’m like, “I don’t want to die on the court. These people don’t love me.”

What would you want to cover now if you were still in production?

I would love to have the guy who had the leading gay conversion center who just came out as gay. That’s so massive to me. It’s a while ago, but there was a young guy of color who was a college student [Naropa University student Zayd Atkinson] who was picking up trash around his dorm, because he was on work study, [and had a gun drawn on him by then-Boulder police officer John Smyly]. Forgive me for having empathy for the cop, he was a …, but he was also a kid. That’s an opportunity to not only be changed but to change so many other people, if they were on together and we didn’t villainize the cop but we villainized his actions or his ignorance. And what if he has been changed, or what if he wants to be? I think that could be really interesting. They went through a traumatic thing together.

Have you ever heard from your anyone in your audience, or someone who’d been on the show, that it changed them?

Not necessarily from the show, but definitely people that I’ve had contact with and stayed in touch with. There’s a woman that went after me on Twitter, a young pro-lifer, and I just went, “Hey, we are never going to agree on this. We disagree on when life begins, and this is not anything to argue — there is no argument.” She has the same name as a character from a show from the ‘80s, and I was, like, “How could I not love you?” And now we follow each other, we never say a bad word about each other. We have totally different political views, but she’ll direct message me and be like, “I had the worst date last night.”

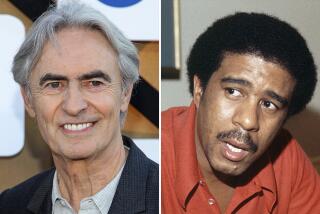

I just think this is a time to connect with people. I feel so cocky talking about it, it’s just a stupid show, but the whole point of this administration is to divide us. I also think it’s interesting what’s happened on the left. It’s almost like there’s a mutated McCarthy era, where any comic better watch anything they say. If you have a special and someone doesn’t agree with every single thing you say on that special ... you know, [Dave] Chappelle says it at the beginning of his special [“Sticks and Stones,” on Netflix], and he still gets so much … for it. I loved it. There were things in it that I did not like. But has there been a special you love and agree with across the board? That’s comedy: You overstep. You say things you might not even believe by the time it comes out. You’re always changing. It’s art. It’s not politics.

From Hillary Clinton singing “Hallelujah” to “Racists for Trump,” “SNL” has embraced liberal politics. So when bigotry is the joke, the series should know better.

I’ve said it before, there’s this kind of “righteousness porn” going on with canceling people over their past, a thing they said or a moment they had, with no earnest hope that they may be changed. We see Megan Phelps-Roper, who grew up in the [anti-gay] Westboro Baptist Church, and we love her because she’s changed. But if we met her seven years ago, would she just have to be someone we had no hope for? She changed because people on social media talked to her warmly. Christian Picciolini was on the show, who was a neo-Nazi skinhead and was changed because someone gave him compassion even though he didn’t deserve it, in his words. So I always [ask myself], “Is this a ‘before’ Christian Picciolini?” It’s not very Jesus-like to just cancel people.

I have to ask myself sometimes too, “Would I want this person to be changed or do I secretly want them to stay wrong so I can point to them as wrong and myself as right?” And that’s dark. And I see it. I see it in people I love or agree with on lots of things. So many hard lines — things need to be black and white and you need to know the answer. It can’t be ambiguous. And I think that’s a mistake.

And that’s why, when you see transcripts of, like, a comic’s joke, or two different people who said the same thing — in one case it could be OK and in one case it could be ... up. Why? Because the intent matters, and what the person’s soul is. My whole first special is in character, and I say, “I’m glad the Jews killed Jesus. I’d do it again.” And someone on the right made a meme of that with a picture of me, like, at the DNC, as if I were giving a press conference. And I get death threats. There was a pastor on the internet — two pastors — saying anyone who smashes my teeth out and kills me is doing God’s work. People are going to get people killed.

Your sister Susan is a rabbi. Do you ever feel like you’re in the same business?

She says that a lot.

But you don’t think so?

Well, it’s not like I disagree, but I don’t really think about it. [Thinks about it.] Yeah, actually. We find meaning and perspective on all things. We interpret. She loves Judaism because she loves to find meaning in every thing. Every small part of everyday everything. And I also interpret what I see in the world around me. But for comedy, I guess. I suppose. I’m not comfortable being the one to say it. But I can see it. We’re both public speakers; we have opinions. She tickles my back.

What makes you hopeful right now?

Well, I’m not really sure how to answer that, except stuff I’m learning in therapy — and maybe this is why religion helps people too. If I just decide everything that happens is essential ... You know, I went to therapy and I go, “I read the news and I repeat negative things and I can feel it eating my insides.” And I was trying to think of something more positive that would be the same reaction, and then I came up with it: What a time to be alive!

You were close to the late Garry Shandling, who thought a lot about compassion. Is it fair to say his spirit informs “I Love You, America?”

Totally, completely. I wish he could have written for it. It’s funny, I’m standing in my apartment looking at a picture of him. He was such a mentor. And not just in comedy or navigating this show business stuff, but human stuff. Everything he learned the hard way, he gave to us on a silver platter. I remember years ago this comic stole a whole bit from me, and I was so frustrated; he tried to buy it from me and I said no, and I found out he was doing it. And I told Garry, and he was just like, “Who cares? That guy can’t write. You can. Write more things.” All this Zen Buddhist stuff he would learn — like, ugh, my friend Harris, my mother and Garry all died in less than two years. After my mom died, he said what Buddhists say is, “Grief, teach me what I have to learn.” That’s a good one.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.