Authenticity in casting: From ‘colorblind’ to ‘color conscious,’ new rules are anything but black and white

When Edward Albee’s estate denied permission for a production of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” because the director had cast a black actor to play a character Albee had specified as white, social media boiled over. How can the theatrical canon remain relevant if creative casting isn’t allowed? Why shouldn’t a black man play a white character? Actors are actors, storytelling in the search for universal truths.

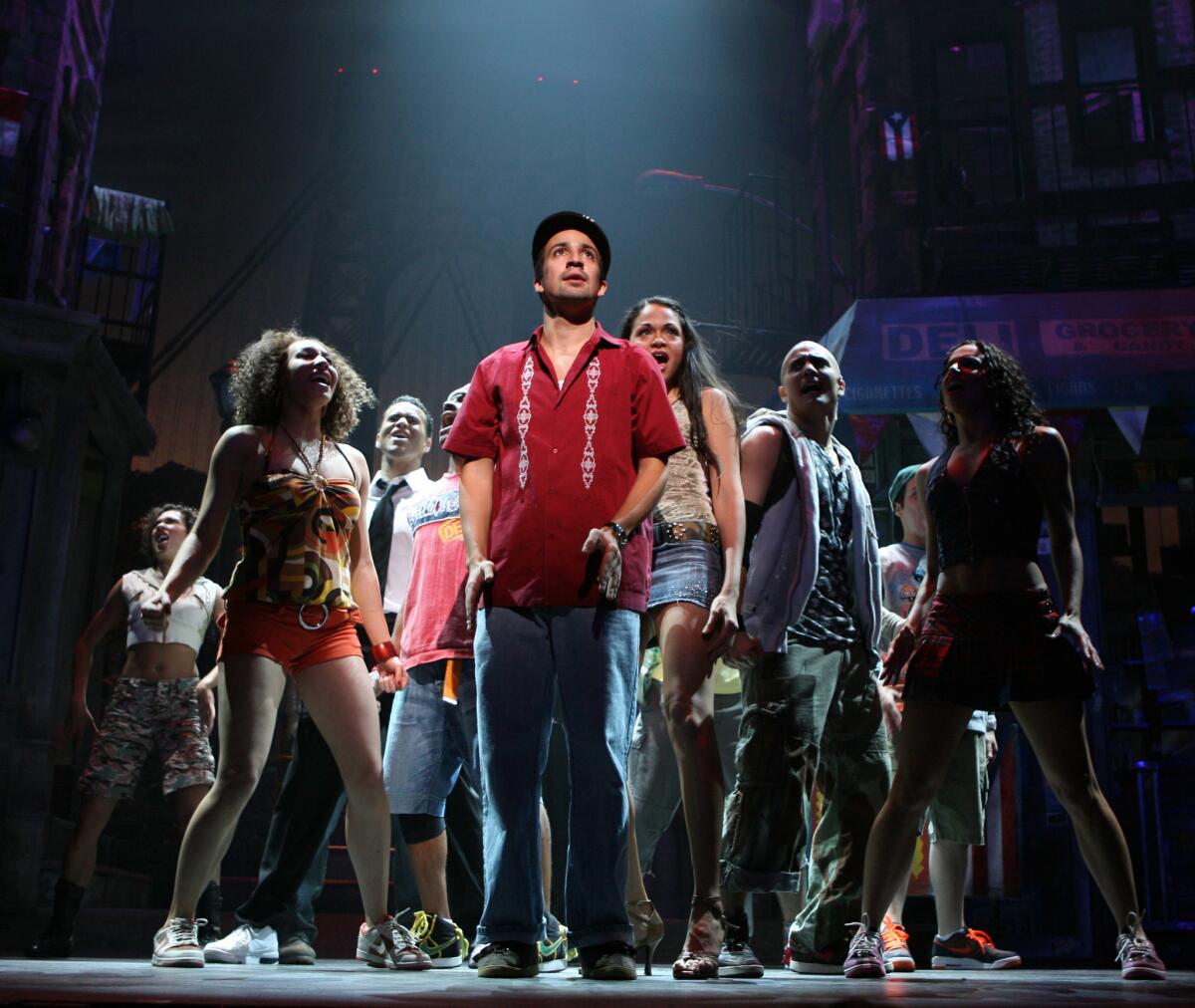

But discord also erupted when a white man played a Dominican American in a Chicago production of

Casting in theater, as well as in film and television, has always been met with criticism. Everyone knows someone who was better for the part. But lately that criticism has taken on an unapologetically political — and often contradictory — bent that reflects both a need for diversity and a new demand for “authenticity.”

Even as audiences celebrate the “Hamilton” multiracial vision of the Founding Fathers, some actors and advocates argue that certain types of characters should be played only by actors who share those characters’ essential experiences. Just a week ago, an advocacy group for the disabled admonished

The increasingly fraught and emotional dialogue pits the progressive ideals of inclusion not just against historical business practices but also the definition of acting itself.

If a role is written for a particular ethnicity, sexual identity, gender or disability, how far should the creative community go to find an actor who checks that particular box? And should the fact that many traditionally marginalized groups are fighting for better representation be taken into consideration? Who has the right to tell what stories? And who gets to make that decision?

Actors love to act. And they can get Oscar-size accolades for showing their reach. Think Leonardo DiCaprio’s nomination for playing a developmentally disabled teen in “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape.” Or Al Pacino’s Oscar win for his depiction of a blind man in “Scent of a Woman.” Or Jeffrey Tambor’s Emmys for his role as a transgender woman in “Transparent.”

Isn’t that the point of acting: to suspend audience disbelief to the point of personal reinvention?

Still, rising tension over the authenticity question could be felt in Tambor’s 2016 Emmy acceptance speech:

“Please give transgender talent a chance. Give them auditions. Give them their story,” he said. “I would not be unhappy were I the last cisgender male to play a transgender female.”

His words signaled a shift from the days when actors like Tom Hanks (who played gay in 1993’s “Philadelphia”), Jake Gyllenhaal (who did the same in 2005’s “Brokeback Mountain”) and John Lithgow (who played a trans woman in 1982’s “The World According to Garp”) were celebrated for their bravery in bringing mainstream visibility to overlooked and often denigrated groups.

The sentiment that, say, transgender, Latino or deaf actors should be given a fair shot at portraying transgender, Latino or deaf characters seems to be growing as producers, directors and others try to balance artistic goals with social responsibility — and the expectations of an increasingly diverse, empowered audience. This is writ large in the American theater, where the term “colorblind casting” — selecting actors without taking ethnicity into account — is no longer in favor. The ascendant norm is “color-conscious casting,” which implies an understanding of the profound implications of skin color. The shift carries potentially radical implications for the art form.

A study by the Asian American Performers Action Coalition found that white actors were cast in 78% of the roles on New York stages between the years of 2006 to 2015, whereas the U.S. Census estimates the white population of the city to be about 44%. Such discrepancies worry activists who note the slowness of change, even after incidents such as the 1989 London opening of “Miss Saigon,” in which a white actor wore prosthetics to change the shape of his eyes. The resulting protests, partly spearheaded by playwright David Henry Hwang, called out the practice and spurred Hwang to write the satirical play “Yellow Face.”

“For a decade or so I was thinking we sort of won the war even if we lost the battle, because we put producers on notice that there was going to be so much trouble if you cast a white person as Asian that you just wouldn’t do it,” Hwang said. Not so anymore, he said, noting the casting of Emma Stone (in the 2015 film “Aloha”) and

Still, the discussion about who should be cast in which roles has evolved, Hwang said. As the theater grows more aware and diverse, the authenticity discussion has evolved with nuance.

“These debates are healthy,” he said. “I think it represents a society that is attempting to come to grips and move forward into uncharted territory.”

Each play or musical must be considered on a case-by-case basis, said Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Quiara Alegría Hudes, who wrote the book for Miranda’s “In the Heights.”

“The danger of creating one hard-and-fast rule is that it diminishes the conversation,” she says. “And, yes, it’s absolutely OK to say this role calls for a specific actor, and if you’re telling me you can’t find that actor, you’re not equipped to do the play.”

Many of the roles in Hudes’ work call for a particular ethnicity, and that should be honored, Hudes said. If it isn’t, then the play is not being produced as it was meant to be produced. It doesn’t convey what she intended the work to convey.

She doesn’t write roles for minorities as a form of political activism, she said. The playwright, who is of mixed heritage and grew up in a diverse Philadelphia community, is simply writing about the world as she has experienced it.

The shift from “colorblind” to “color-conscious” may be attributed partly to the growing diversity of stories being produced. In eras past, when the vast majority of tales unfolding onstage were written by white playwrights about white characters, it took colorblind casting for an actor of color to be seen.

But now we’re in the era of “Hamilton.” A better term is “color-conscious,” said Diep Tran, associate editor of American Theatre magazine, who writes a monthly column on equity, diversity and inclusion. “Color-conscious” means “we’re aware of the historic discrimination in the entertainment industry,” she said, “and we’re also aware of what it means to put a body of color onstage.”

Snehal Desai, artistic director of the Asian theater company East West Players in Los Angeles, the longest-running theater of color in the United States, agrees.

“The thing about colorblind casting is that it denies the person standing in front of you,” he said. “It ignores identity, and for people of color, that further alienates us.”

In the recent case of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” in Portland, Ore., casting a black actor in the role of Nick was a color-conscious choice, director Michael Streeter said by email. He believed the decision would add depth to the play.

“The character is an up-and-comer,” Streeter said. “He is ambitious and tolerates a lot of abuse in order to get ahead. I see this as emblematic of African Americans in 1962, the time the play was written.”

The estate of Albee, who died last year, countered that the role was written specifically for a Caucasian man. (The playwright’s character description is 28 and “blond, well put-together, good looking.”) To alter that would fundamentally change the meaning and message of the play, the estate said.

In the resulting social media firestorm, some pointed out that “Hamilton” had done the same thing, only in reverse — casting actors of color to play white historical figures.

Tran called that line of thinking nonsense.

“When you have something like ‘Hamilton,’ which was written to give opportunity to actors who would normally not get that opportunity, it’s different than taking a job away from a white actor, because that white actor has the entire American canon to play with,” she said.

Tran also argued that an audience should want to see a production from that canon, exactly as the author intended, only so many times. Inflexibility puts the work in stasis, whereas theater should be a living, breathing art form.

“What does this 50-year-old play say about the time we’re living in now if we don’t put it in a modern context?” she asked.

These debates are healthy. I think it represents a society that is attempting to come to grips and move forward into uncharted territory.

— David Henry Hwang, playwright

Casting plays in a modern context makes financial sense as well, Hwang said.

“If people like to see themselves on stage and screen, then our artistic fields aren’t sufficiently preparing for audiences of the future,” he said.

The conversation will change in two or three generations as the country becomes more mixed racially, East West Players’ Desai said. He added that when it comes to representation, people of color long for consideration that extends beneath their skin.

“There are regulations about asking people their age or race,” he said. “As a person of color, I want to be seen as a whole person and not just an Indian.”

The danger of seeing only color, sexuality or disability is that it can lead to a ghettoization. Take the example of transgender actors, said Jon Imparato, the Los Angeles LGBT Center’s director of cultural arts and education. Since Caitlyn Jenner went public as transgender two years ago, Imparato’s phone has been ringing with requests for recommendations of good transgender actors.

“I say, ‘Is she a hooker and does she get murdered at the end? If so, we want nothing to do with it. We’ve heard that story,’” he said.

In this day and age, Imparato believes all trans roles should go to trans actors — although the same doesn’t hold true for gay roles. Why? First, it’s illegal to ask about sexuality when casting. Second, plenty of gay actors now play straight roles and vice versa, he said.

“For me it always comes down to who’s going to serve the play better? Do I have enough diversity in my cast?” Imparato said. “And are they the right actors?”

AUTHENTICITY IN CASTING:

Stuck on the sidelines: One transgender actress’ story

Q&A with the artistic director of Deaf West Theatre

Timeline: 200 years of authenticity, or lackthereof

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.