Huntington Library sets out to decode thousands of Civil War telegrams hidden for a century: ‘It’s mind-boggling’

The Huntington Library has launched a crowdsourcing project in which volunteers will transcribe or decipher nearly 16,000 Civil War telegrams from Abraham Lincoln, his Cabinet and Army officers.

- Share via

They ticked out news of typhoid, scurvy and fear. They spoke of long marches and vast battles. They hummed with frailty and humor, fretting over drunken soldiers and praising the unwavering president of a fraying republic. They clacked in broken rhythms that rang with the ominous: “We will not remain undisturbed tonight. Even the Rail Road men have been ordered to leave.”

The 15,971 telegrams — hidden in a wooden foot locker for more than a century — scrolled like a Twitter feed through the Civil War. The messages from the Union side, many tapped out in code to elude Confederate forces, carried the urgings and reflections of Abraham Lincoln, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and other prominent players. But most echo with the thoughts and schemes of colonels, infantrymen and lesser-knowns that offer a peek into the bureaucracy and machinery of war.

“It’s mind-boggling and unpredictable,” said Olga Tsapina, curator of the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens’ trove of 35 leather-bound ledgers and documents relating to telegrams sent between 1862 and 1867. “We don’t really know what is in here. Every single telegram has a story behind it, from the president to the greatest generals and to the privates and telegraph operators. It’s like putting together a huge jigsaw puzzle.”

See the most-read stories this hour »

The telegrams were part of papers kept by Thomas T. Eckert, a Lincoln confidant and head of the U.S. military telegraph office at the War Department. The Huntington has started a Decoding the Civil War crowdsourcing campaign that relies on volunteers using cipher charts to unravel secret texts. So far, more than 2,100 “citizen archivists” and war buffs worldwide have transcribed less than one-third of the collection, which includes encrypted messages sent in grids.

The telegrams resonate with heartbreak, warning, sarcasm and conniving. They recount visceral images with unintended poetry and lay bare the cost of conflict and the inclinations of men accustomed to trenches and disease. They whisper of spies, grievances, draft riots, bad weather, downed cables, deserters, gold and cotton markets and the latest from the battlefield, such as Lincoln’s musing that Grant’s forces have “Petersburg completely enveloped” and have captured “about twelve thousand prisoners & fifty guns.”

In a telegram discussing troop movements, Gen. William T. Sherman drifted into sorrow: “my eldest boy Willie, my California boy, nine years old died here yesterday of fever and dysentery contracted at Vicksburg. His loss to me is more than words can express.” Some are less stoic. A telegraph sent by J.W. Carver from Point Lookout in Maryland informs Eckert: “Family matters require my immediate attention at home for a few days. If not attended to at once I am utterly destroyed.”

The language comes through so loud and clear that it puts you back on your heels.

— Mario M. Einaudi

The telegrams, clicked out by about 1,500 telegraph operators, many of whom did a bit of editorializing, are remarkable literature, shorthand sketches of a United States at the brink of collapse. The messages traveled over an estimated 15,000 miles of lines and revolutionized war-time communications from the days of horseback messengers. A mix of the thrilling and the mundane, they bear witness to unheralded lives caught in a sweeping historical narrative whose prejudice, racism and defiant politics reverberate today.

In 1865, Grant -- who was known to light his cigars with burning telegrams -- wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton: “I would call attention to the fact that our white troops are being paid whilst the colored troops are not. If paymaster could be ordered here immediately to commence paying them it would have a fine effect.”

Many were less lofty. The headquarters of the Army of the Potomac wrote Eckert: “I do not [know] of anything that you could send here to benefit the men unless it is one [barrel?] of good whiskey so that they can have one ration of it daily. I can get it here but it is a very bad article. Caldwell is getting better. D. Doren” One telegraph operator, desperate for a change of clothes, wrote to Eckert: “Have you any objections to my going to F to get some more clean duds on me/did not think would be here as long & did not bring any with me. Snyder.”

The power of the telegrams is in their “every day-ness. There’s no filter,” said Mario M. Einaudi, who is overseeing the library’s collaboration with Zooniverse, a research platform, to digitize the documents and put them online at the Decoding the Civil War site. The project still has an open invitation for volunteers.

“The telegrams were actually considered lost,” Einaudi said. “They’re significant in that what we’re making available to people is raw history. The language comes through so loud and clear that it puts you back on your heels.”

The war was rife with charlatans, grifters and opportunists. A telegram from a major general in Washington seeks the arrest of a corrupt Treasury agent in Mississippi: “It is important that the person of Mr I H Stevens local special agent of the U S Treasury at Natchez Miss be seized & sent to this place for trial for complicity in private cotton speculation.” Another officer was affronted by the aesthetics of telegraph poles: “A clamorous Lt Col says one of the poles disfigures the garden – I have received from him very unpleasant words on that account.”

The telegram ledgers were taken by Eckert, who would later become president of Western Union, when he retired from the War Department in 1867. Until his death in 1910, Eckert -- who left a contested will and had a family cat named Honeybubbles that sat in a highchair at the dining table -- had apparently kept the documents in storage. They surfaced in 2008 and were sold at a New York auction for $36,600 to the William Reese Co., which specializes in rare books.

“The cataloging didn’t explain how important the documents were,” said Reese. “It was a classic case of hiding in plain sight.” Several years later, the collection was in the care of Reese and Seth Kaller, a historic documents dealer, who was negotiating with another library when he contacted Tsapina at the Huntington. In 2012, Kaller sold the cache to the Huntington for an undisclosed amount much lower than the $1 million he believes it may be worth.

“This was one of the most undervalued lot of archives that I’ve handled,” said Kaller. He added that few knew the scope of the telegrams and that the 2008 recession kept potential buyers out of the market for historical papers. Tight acquisition budgets also prevented many research institutions from making offers. “I wanted it to go to a research library and for it to be made public. It’s a spectacular, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” He paused and noted: “I kept the foot locker.”

The documents had been “stored in a clean, dry place,” said Tsapina. “They reeked of mothballs.”

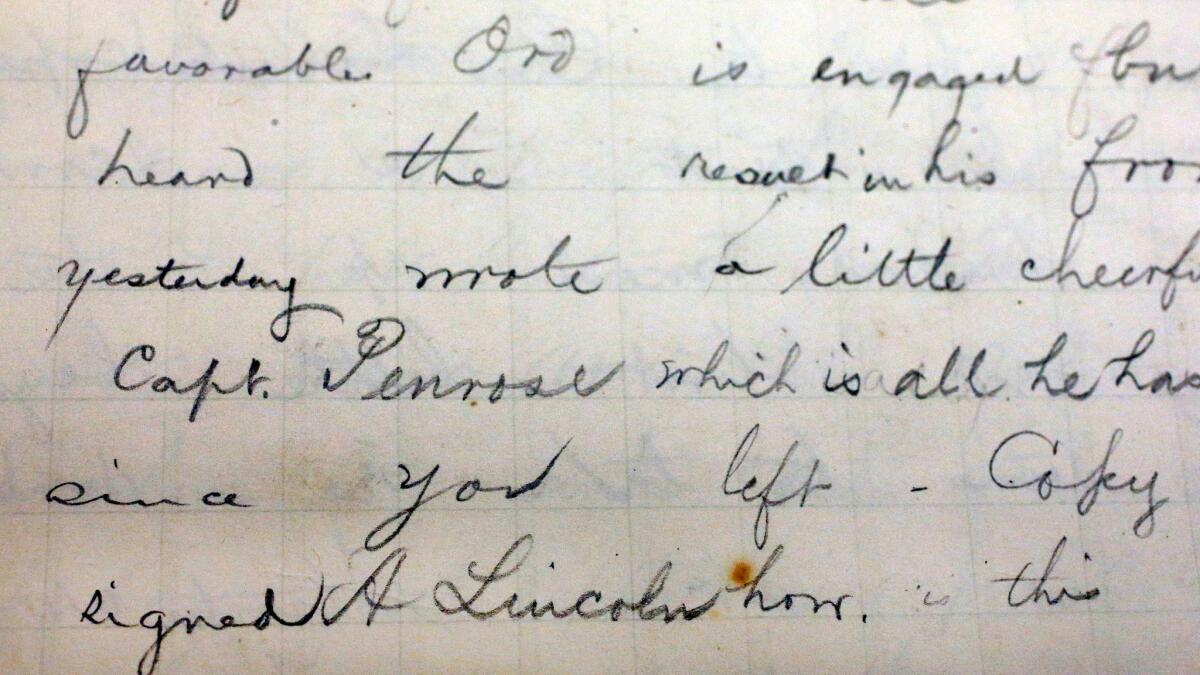

The telegram ledger pages are crisp and slightly yellowed. They are written in pencil and ink and, depending on the operator’s penmanship, flow in either cursive or scrunched lines.

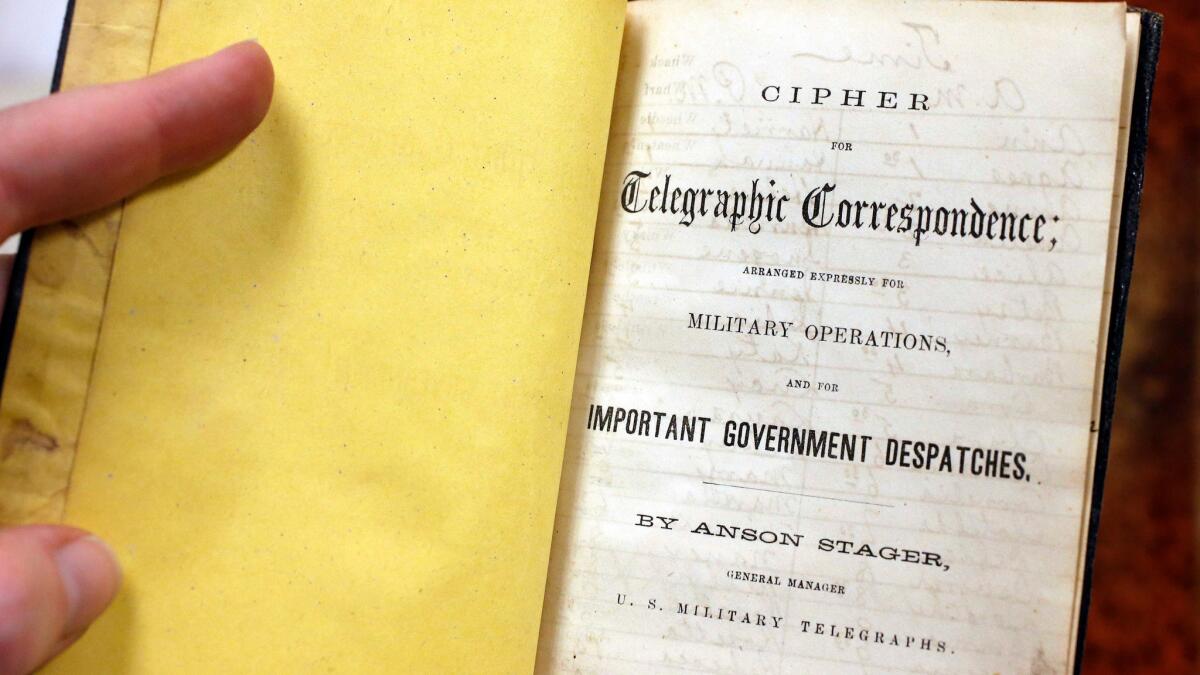

Some contained codes, devised by Anson Stager, general manager of U.S. military telegraphs, that inserted decoy words or arbitraries into messages that were unscrambled with cipher charts. “Rabbit” and “Racine,” for example, might transcribe into “mortars” and “enemy.”

Eckert’s office in the War Department rattled through the nights and was often a refuge for Lincoln, who would wander over from the Executive Mansion to keep abreast of war in a country he described as a “house divided against itself.” The president, who updated wife Mary Todd on the latest news, closely followed the field correspondence of Charles Anderson Dana, a former New-York Tribune reporter who signed on as an assistant secretary of War.

“By 1863, Lincoln could communicate with his commanders in the field almost in real time,” said Daniel W. Stowell, director and editor of the papers of Abraham Lincoln at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Ill. He added that the telegraph office “became a secondary Cabinet room and command post. During major battles, Lincoln spent anguished hours reading the latest dispatches, agonizing over Union setbacks and rejoicing in triumphs.”

The documents, which were shown by the Huntington in 2012 as part of a Civil War exhibit, include about 500 telegrams sent by or addressed to Lincoln. There are no plans to display them in the immediate future. “I don’t believe they’ll be [major] secret revelations coming out of these telegrams,” said Stowell. “But the immediacy of them … is a new way to see the fog of war.”

The telegraph operators, most of whom were civilians, contended with encroaching enemy regiments, lack of pay, disrupted supply lines and soreness in arms and fingers known as “glass arm.” Their cipher codes were kept secret even from generals; Grant once had two operators arrested for barring him from a telegraph room. Operators often added personal asides, known as “tails,” to dispatches, such as “how is old Abe” or “what a disagreeable day” or the foreboding “great battle very soon,” sent the same day the Battle of Gettysburg started.

In June 1863, less the a month before the battle, Maj. Gen. Robert Schenck sent a telegram describing the massing of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army: “Their Cavalry force at Culpepper is probably more than thrice twelve thousand. I would advise that the militia of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Ohio be at once called out as there is doubtless a mighty raid on foot.”

Two years later, Lee’s army was surrounded and in tatters at Appomattox, Va. “If the thing is pressed I think Lee will surrender,” Union cavalry Gen. Philip Sheridan wrote in a telegram. Lincoln responded in a telegram to Grant: “Let the thing be pressed.” On April 9, 1865, Lee met Grant in the sitting room of Wilmer McLean’s home in Appomattox and surrendered his 28,000 troops.

A week later, the telegraph lines clattered with news of Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theatre in Washington and the chilling way it was put into words by Stanton: “The president continues insensible and is sinking.” John Wilkes Booth, who fled the presidential box at the theater, leaving behind a spur and a hat, was identified as the gunman. Hours passed. The president died at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, 1865. “Now,” said Stanton, “he belongs to the ages.”

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

ALSO

How a new dance gets made: Behind the scenes at American Contemporary Ballet

‘No Asylum: The Untold Chapter of Anne Frank’s Story’ revealed via her father’s letters

Why the exterior of D.C.’s soon-to-open African American museum is an exciting sign of what’s inside

Celebrating L.A.’s Central Library’s 90th birthday with — what else? — a new book

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.