Column: How to remake the L.A. freeway for a new era? A daring proposal from architect Michael Maltzan

- Share via

Can you picture a freeway that’s good for the environment?

That collects storm water? That produces clean energy instead of pollution, quiet instead of noise?

That stitches a neighborhood together instead of slicing it apart?

I wrote a series of essays last year raising some of these questions — and in a broader sense wondering how we might reconceive the Los Angeles freeway, the aging product of 20th century infrastructural logic, for the 21st.

This year — which happens to mark the 60th anniversary of the interstate highway system — we’re taking that inquiry an important step further, publishing two design proposals that dramatically remake stretches of L.A. County freeway.

The proposals are meant to act simultaneously at the local and regional levels. Carefully tailored to their sites, they’re also prototypes for a new way of thinking in Southern California about the relationship between the freeway and the public good.

The first comes from Michael Maltzan Architecture, a Los Angeles firm best known for the One Santa Fe apartment complex in the Arts District, the Star Apartments near Skid Row and the forthcoming Sixth Street Viaduct spanning the Los Angeles River. It will be followed by a proposal from Stoss Landscape Urbanism, a firm led by Chris Reed, associate professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, to remake the stub end of the 2 Freeway.

Neither firm was paid by The Times for this work. In each case the designers were eager to help the public better understand how a reimagined L.A. freeway might look and how it would operate.

Maltzan’s design reimagines the Arroyo Seco Bridge, a section of the Ventura Freeway (also known as the 134, or more formally State Route 134) south of the Rose Bowl and just north of the 1913 Colorado Street Bridge.

Without affecting the flow of traffic, it would wrap the freeway bridge, built in 1953 and expanded in 1971, inside a sort of tunnel, what Maltzan describes as a “new infrastructural overlay” stretching nearly three-quarters of a mile.

He describes the proposal, produced in collaboration with the Los Angeles office of the engineering firm Arup, as “an environmental machine designed to enhance rather than replace the existing freeway.”

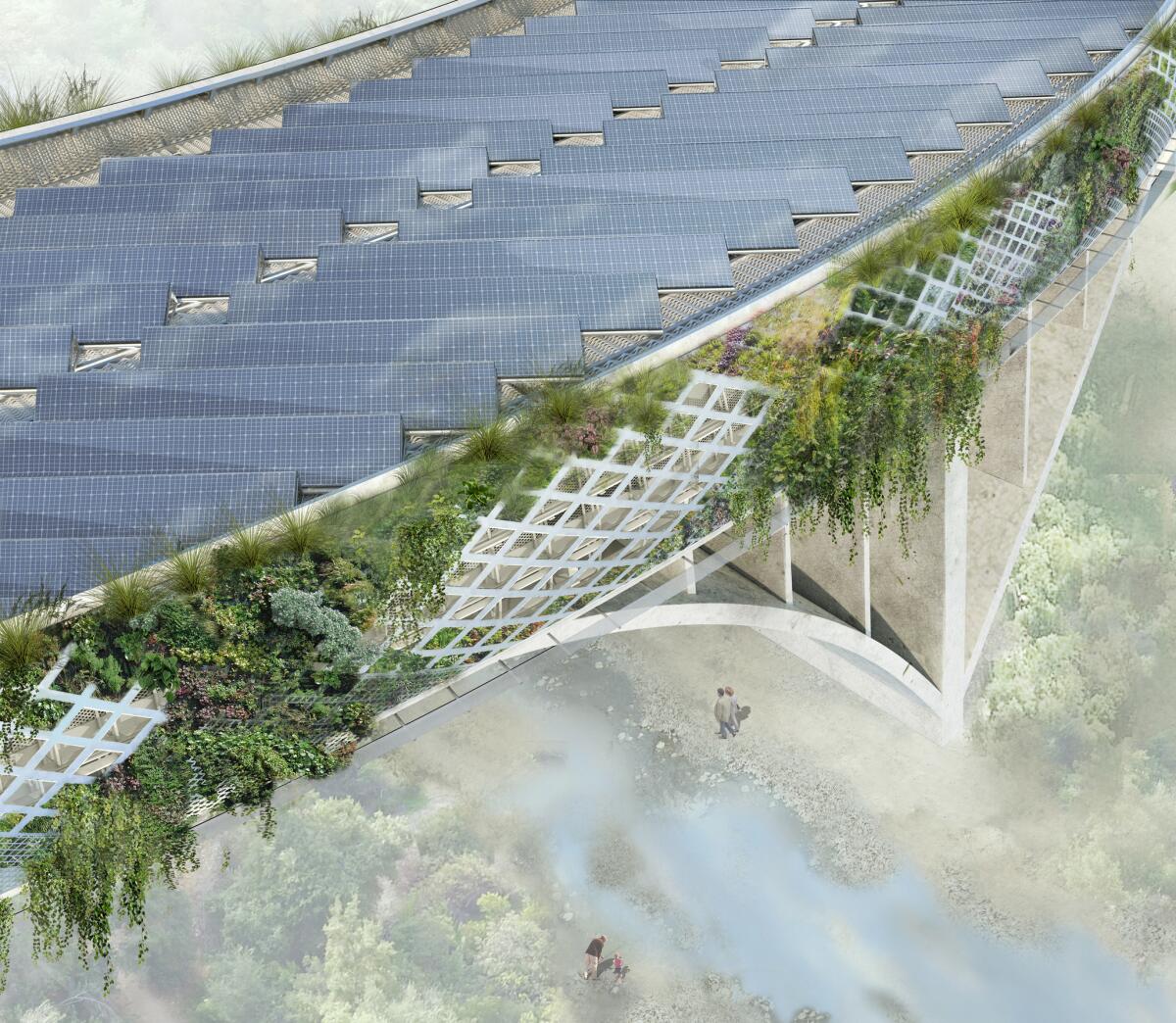

Photovoltaic panels would produce enough electricity annually to power 600 homes.

The overlay would include acoustically insulated walls capable of reducing traffic noise, which has a severe effect up and down the Arroyo and throughout this part of Pasadena, by 65%, according to Arup. A perforated aluminum ceiling would direct auto emissions through concrete “lungs” made of precast concrete treated with titanium dioxide, capturing 516,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year.

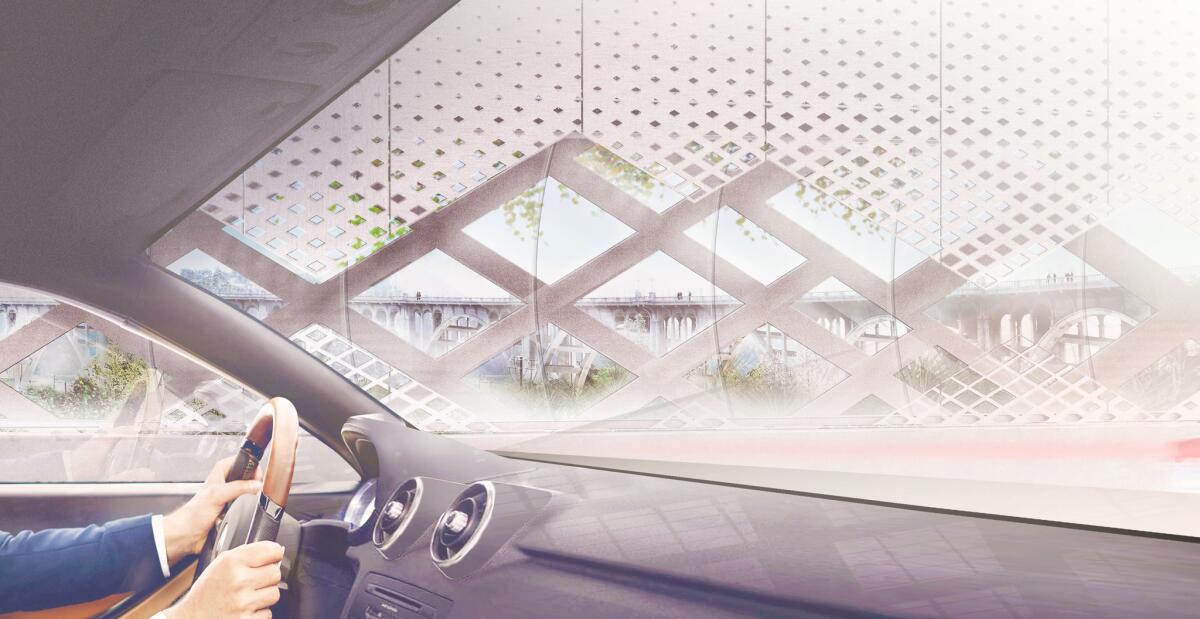

Transparent polycarbonate panels at eye level would maintain views from the freeway bridge for drivers and passengers; according to Maltzan the plan is “a design solution that celebrates the experience of driving over the Arroyo Seco while sustainably integrating the freeway into its immediate context.”

The new structure would collect rainwater, storing it in a pair of drums big enough to hold 750,000 gallons each. Some of that water would be used to maintain hanging plants on the exterior of the tunnel. The rest — as much as 5 million gallons per year, according to Arup — would be added to the city of Pasadena water supply.

A field of photovoltaic panels along the top of the tunnel would produce about 6 million kilowatt-hours of electricity annually — enough to power 600 homes.

Maltzan proposes that the cost savings made possible by the solar array — an estimated $1 million per year — be similarly fed back into the city, used to boost the budgets of the half-dozen Pasadena Unified School District campuses located within two miles of the freeway bridge.

To be approved and built, the plan would require cooperation among the city of Pasadena, Los Angeles County and Caltrans. But its location offers some political advantages.

Because Pasadena operates its own department of water and power and has a school district independent from the giant LAUSD, the city is in a unique position to consider re-imagining its infrastructure — and to control new revenue produced by this kind of upgrade.

Certainly it would require a significant philosophical shift for Caltrans to approve the idea of cities piggybacking on state infrastructure to generate local revenue. But freeways in California have for many decades devastated communities — tearing some of them apart during construction and producing noise and air pollution once in operation.

The plan takes the kind of green landscape synonymous with the L.A. backyard — and with private wealth — and extends it to the public realm.

We need to strike a more equitable balance, even if it requires an upfront investment of public funds. (Maltzan and Arup have not worked out a detailed cost estimate for the overlay.) We need to consider changes more ambitious than the large cap parks that have already covered sunken stretches of freeway in Dallas and Seattle and have been proposed for Glendale and other parts of Southern California.

Maltzan’s proposal turns on its head the conventional wisdom about the relationship between freeways and the communities that surround them. If you look at the diagrams his firm and Arup have developed to accompany the design, what you see seeping out from the new freeway bridge into nearby neighborhoods is not a plume of pollution but a spreading zone of benefits: an expanded wildlife corridor, better equipped schools, improved air quality.

The plan takes the kind of green landscape synonymous with the L.A. backyard — and with private wealth — and extends it to the public realm, where it also has the benefit of reconnecting two halves of the Arroyo bisected by the 134.

What is perhaps most promising about the proposal is the potential to use it in other locations — the extent to which, as Maltzan puts it, it is “expandable to other freeways.”

There are few bigger challenges facing contemporary Southern California than the question of how to maintain — or even better, redesign — our most muscular pieces of infrastructure, which were once synonymous with region-wide optimism but are now looking worn and inflexible.

THE FREEWAY REIMAGINED: A colorful vision for the 2 Freeway spur, remade as an elevated park »

The first step is to start seeing our infrastructural networks not merely as single-use conduits of one kind or another — to carry cars, storm water or consumer goods — but as platforms for a new kind of urbanism, holding housing or making room for innovative ideas about energy or water.

For a full generation we’ve been trying to turn the Los Angeles River into something more than a concrete-lined flood-control channel. Yet at 51 miles long the river is small change compared to the massive freeway network, which covers 527 miles across Los Angeles County.

That’s more than 10 L.A. Rivers laid end to end. Time to get started.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

ALSO

Frank Gehry's controversial L.A. River plan gets cautious, low-key rollout

Design team led by Mia Lehrer picked for new downtown L.A. park

Why the Expo Line to Santa Monica marks a rare kind of progress in American cities

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.