The Hollywood Bowl’s magicians of sound

- Share via

When the issue of amplification came up at a Hollywood Bowl patrons’ breakfast in 1935, one man strongly admonished the institution against attempting “to improve God’s perfect handiwork.”

“So long as we are in charge there will be no mechanical devices placed there,” Mrs. Leiland Atherton Irish, executive vice president and manager of the then Southern California Symphony Assn., assured him that early August morning.

Still in charge but clearly having changed her tune a year later, Mrs. Irish went to Union Station to warmly greet Dr. Harvey Fletcher, the head of Bell Laboratories in New York. He had journeyed across country at the behest of the celebrity guest conductor and technology maven Leopold Stokowski to install microphones, 500-watt amplifiers and speakers above the the Bowl’s shell.

Commenting on the first experiments a week later with the system in Los Angeles Philharmonic programs conducted by Stokowski and the orchestra’s more sober music director, Otto Klemperer, Times music critic Isabel Morse Jones felt little was gained.

The double basses were too loud (though “perhaps not too loud for Mr. Stokowski,” she wrote). The violas were unnaturally equal to the violins.

A proper wood shell in a 14-year-old and, at that time, 19,000-seat amphitheater said to have remarkable natural acoustics, Jones suggested, would be “more profitable and less costly than hiring a scientist.”

There is never any turning back from technology. Even so, Stokowski’s vision of a sonic orchestral wonderland for the masses (he, incidentally, began taking meetings with Walt Disney to work on “Fantasia” the following year) led to inevitable controversies and complaints as the Bowl continued to experiment with amplification over the next three quarters of a century.

It has proved a unique technological challenge to acoustically tame this massive outdoor venue with a full summer of almost daily symphonic and pop programs plopped in the heart of the country’s second-largest city, bordering a freeway and lacking a reverberant shed as you more often find at more rural arenas. Among the attempts have been different types of shells, the installation of acoustical balls and pillars designed by Frank Gehry, microphones of all types and sizes and placing loudspeakers around the Bowl as well as in pillars in front. But there were always trade-offs. Either the sound was too tinny or too boomy, too muddy or too clinical, too loud or not loud enough.

Last year, though, a new sound system put an end to most objections. The scientists have succeeded.

But they’re not scientists.

Morning at the Bowl

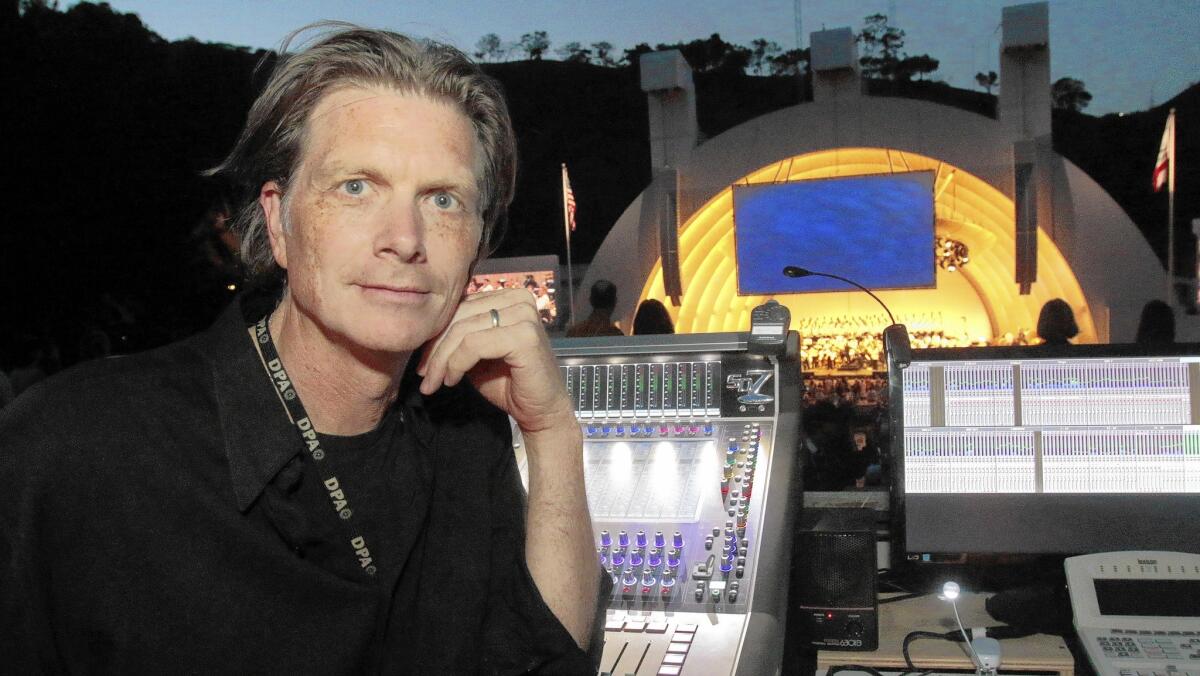

I recently spent a morning with Fred Vogler, the Bowl’s sound designer, as he and Michael Sheppard, head of audio for the Bowl, worked the massive soundboard in a cramped booth set in the first section of benches behind the boxes. Gustavo Dudamel was on stage rehearsing the L.A. Phil.

Tall with long red hair and commonly dressed in black, Vogler, 50, has a friendly intensity and the look of a former rock keyboardist. He is largely responsible for the final sound that comes out of the loudspeakers at nearly all the Bowl concerts, be they Boz Scaggs, Mötley Crüe or the decidedly un-motley L.A. Phil.

Vogler’s background is rock, and he still performs in a group called Industrial Monk, but he says he was always the guy in the band who wanted to help with the set-ups and recording. He naturally gravitated into working in recording studios and from there to the concert world. Vogler also serves as a sound designer at Walt Disney Concert Hall, oversees the live recordings of both the L.A. Phil and L.A. Opera and works as an audio consultant with Disney architect Frank Gehry and acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota on construction of other halls.

His job at the Bowl is mixing the sound on a room-long, highly computerized, brand-new mixing console that he operates with Sheppard, who is responsible for the sound crew on stage.

Demonstrating some of what is possible while Dudamel rehearsed the orchestra in “Cavalleria Rusticana” (the Pietro Mascagni opera he would perform three days later), Vogler jauntily zoomed a slider forward, causing the strings to massively caress wide spaces in a manner better suited for, say, Aaron Copland’s cowboys than rustic Italian villagers. Pushing another slider caused winds to squawk like dinosaur-sized geese; another brought the illusion of a brass band marching through the box seats with cinematic magnificence; another turned the bass drum into thunder. An off-stage harp might as well have been in your face.

Not only does the new system allow all this to happen with greater flexibility than before but also with enhanced immediacy. Bright instrumental colors dazzle like never before.

That is precisely what Vogler doesn’t do to the L.A. Phil, although the louder, gaudier weekend shows do allow for more flexibility.

“I love these shows,” he admits. “I get a kick out of putting it all together. The rock shows are flashier, but the flash is also a distraction. What I really like best is focusing on Gustavo.”

At the Bowl’s opening concert in 1922, a critic wrote that sound “mellows beautifully in the open.” Even from the back benches, he enthused, “the fine tonal fiber of the stringed instruments carried with a beautiful clearness.”

There was also great silence in the Cahuenga Pass way back when. The wife of French conductor Pierre Monteux called the Hollywood Bowl silence “the impressive of any and the most inexplainable.”

Recapturing the sound, the silence and, most of all, the magic began to seem a losing battle as the amphitheater grew in size (it held 5,000 on opening night and was judged huge), as concrete shells replaced wooden ones, as the Cahuenga Pass was modified for the Hollywood Freeway in the 1940s, thus destroying some of the canyon’s natural acoustical properties, and as traffic noise and aircraft exponentially intensified ambient noise.

Vogler’s job is to make all that bad stuff go away. He demonstrated the effect of turning the amplification off altogether. The orchestra could be heard fine, especially in the lower seats, but it lacked vibrancy.

“What we have to do,” Vogler says, “is embrace what is naturally there and find a comfortable way to make it bigger.” For the most part that means discrete boosting without interfering with the instrumental balances created by the conductor. “Less is best” is Vogler’s motto.

Everything, however, matters. Different kinds of microphones are used for different orchestral sections, and the movement of a mike up or down, an inch to the right or left, makes a noticeable difference. Individual mikes may be used to highlight individual instruments.

If there is an off-stage organ, it has to be made to sound in the distance. If the cellos are on the audience’s right, they should sound like they are there. The effect should be the same for those sitting up close and those far, far away.

To do all this with clarity, believable color and a visceral but not artificial-seeming heft is an almost impossible task for two towers of loudspeakers on either side of the stage and a smaller center cluster.

Last year, Vogler selected and oversaw the installation of $1 million worth of new sound equipment by a specialist French firm, L-Acoustics, which he has further tweaked this summer. He says the ideal system might also have included tubular loudspeakers along the sides and over the audience’s heads like the one he installed for outdoor concerts at the Frank Gehry-designed New World Center in Miami Beach, home of the Michael Tilson Thomas’ New World Symphony. That setup creates an almost supernaturally lifelike sound in a park setting for a couple thousand listeners.

But in Miami, Vogler had the advantages of not having to worry about sightlines, a substantially smaller space and plenty of humidity. Sound travels faster in water. The worst possible atmospheric conditions, he says, are when it’s hot, dry and windy — the typical Southern California Santa Ana.

There are also four or five technical rehearsals for the Miami concerts. At the Bowl a single morning rehearsal for the evening concert must suffice. Sheppard and his crew regularly finish taking down an evening show at midnight and six hours later begin loading in equipment for the morning rehearsal, which begins at 9:30. An orchestra assistant marks up a score for Vogler with cues for entrances. Both he and Sheppard, who was a horn player, read music.

Soloists are another issue. They move around, and singers more so than instrumentalists. Equipment breaks down. If the conductor chooses at the last minute to speak to the audience, as Dudamel might, that needs to be dealt with on the fly.

Where Vogler is likely to be the most proactive is with disturbances. “If there’s a helicopter coming in,” he explains, “and it’s a quiet passage, I’m going to give the sound a little lift to try to keep people’s attention on the music.”

Video adds another layer of complication. Close-ups produce the psycho-acoustical effect of a player seeming to sound more prominent, yet the sound and video crews work independently, so Vogler never knows what to expect.

Conductors may or may not get involved. When Tilson Thomas was guest conducting last summer, he came up to the booth to experiment with balances. Dudamel will occasionally visit the technicians, but guest conductors tend to be so preoccupied with getting their bearings in a single rehearsal they have no time for anything else.

As impressive as the new equipment is, it isn’t everything. The new Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills also has the latest L-Acoustics audio components. The performances I’ve heard in an indoor hall barely a 40th the size of the Bowl have not been as pleasing as now sitting in the immense Cahuenga Pass.

Vogler chalks at least some of that up to the experience of working at the Bowl for 11 years. Sheppard has a 30-year history with the venue. Most in his crew are also longtime veterans. Rock bands frequently bring their own sound systems and engineers, and the result can be flat and loud (though not too loud — another of Vogler’s jobs is to enforce the County’s regulations on volume).

This, then, raises the inevitable question of Disney’s sound system. The hall has proved notoriously difficult to amplify. The equipment, never fully satisfactory, is overdue for an upgrade.

“We’re working on it,” Vogler cautiously remarks, breaking off to adjust a cue for small ensemble that was originally meant to be off stage but that Dudamel has just decided he would make work from the stage.

“Sometimes, it’s a real rally car out here,” Vogler says. “I’m driving and I’m breaking and accelerating and Mike’s navigating, hard turn left in 50 yards. It helps to like a lot of different kinds of music.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.