Review: Something’s missing from the newly reinstalled antiquities collection at the Getty Villa

- Share via

During the 15 months that it took to reinstall the collection of ancient art at the Getty Villa, roughly half the galleries remained open at any given time. Bits and pieces of the ongoing transformation could be glimpsed, but not the whole story the museum wanted to tell.

Now that the, uh, herculean task of rethinking the presentation of Greek and Roman art is done, the museum emerges refreshed, renewed and looking at least as good as it ever has. But it also comes with one major surprise, plus one big disappointment.

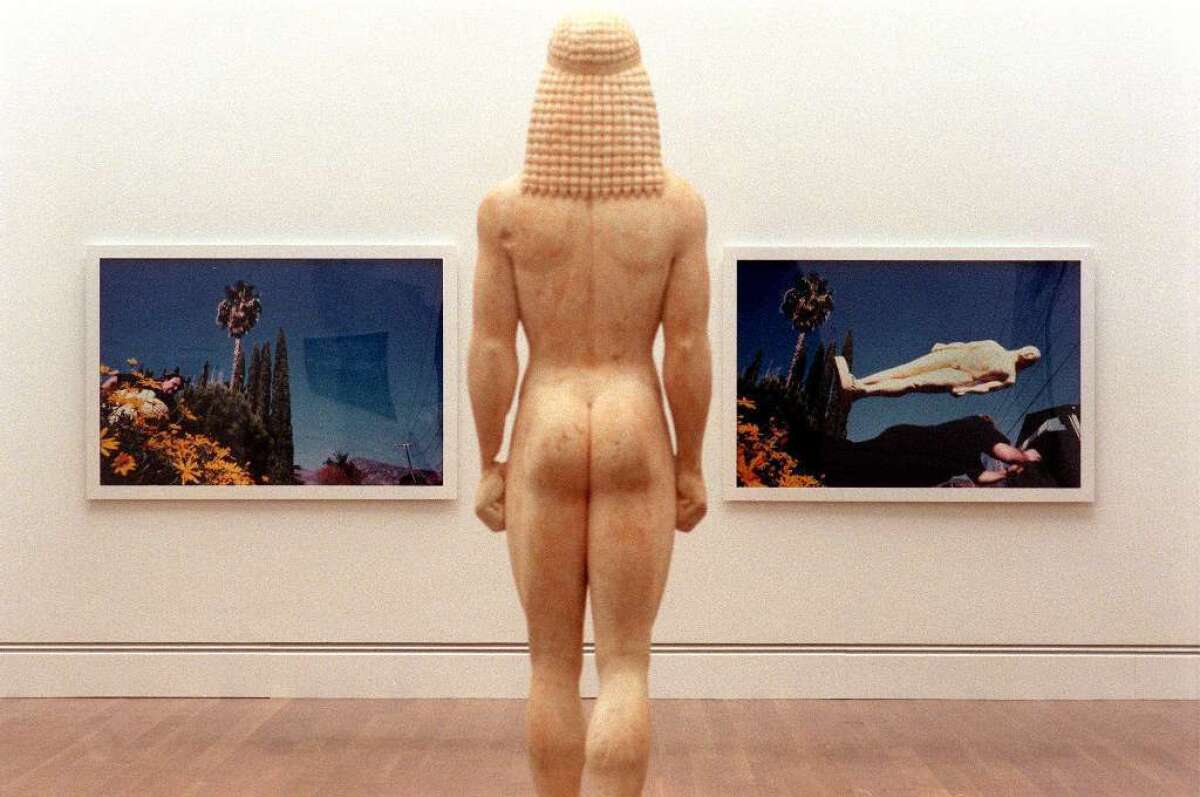

Unexpectedly, the Getty kouros, a controversial sculpture even before the museum acquired it more than 30 years ago, has been removed from public view. The work is now in museum storage.

For decades, the life-size carving of a standing nude youth carried one of the most distinctive labels of any work of art in an American museum: “Greece (?) about 530 B.C. or modern forgery.” The label encapsulated puzzling issues about the work, whose questionable status as dating from the archaic dawn of Western civilization had been the focus of scholarly and scientific research, debate and international symposiums for years.

It was oddly refreshing to see a museum frankly acknowledge the difficulty even the most knowledgeable among us can face around a work of art. Now, with nary a word of explanation from the Getty, the kouros is gone.

According to the museum’s director, Timothy Potts, the kouros has not been downgraded to the status of a forgery or definitively determined to be a fake. The distinctive labeling, also appended to the sculpture on the museum’s collection website, still stands.

Potts said only that the consensus of art historical study, once divided, now leans against its authenticity. Papers regarding its history of ownership have long been known to have been faked, so where it came from is unknown. But the sculpture has always been a puzzlement for its pastiche of myriad stylistic details, which bring together features recognized from different artistic centers at different times in a work unlike any other known to exist. To many trained eyes, the Getty kouros just doesn’t look right.

Scientific analysis, meanwhile, is now ambiguous. Science is what had kept hopes alive that the kouros might be genuine. The surface of the marble shows a type of weathering once thought possible only through the passage of centuries and impossible to fabricate artificially. But that determination has since been proved wrong.

For much of the last year, Potts added, an antiquities conservator has been conducting further tests, but they aren’t yet complete. Coupled with the apparent consensus of historians of ancient Greek art, the scientific ambiguity seems to have tipped the scales against including the kouros in the reinstalled galleries.

That might be a reasonable decision, but it leaves the public in the dark. Transparency is key. One easy option would be to simply include a didactic text in the appropriate gallery of other archaic Greek art explaining the status of one of the Villa’s most famous works, now conspicuously missing.

Another, more elaborate possibility would be a small show in the Villa’s temporary exhibition gallery. The Getty could even have fun with it: In 2000, artist Martin Kersels made a marvelous series of photographs of himself clutching a full-scale replica of the kouros and leaping into the void with it — a witty celebration of risk, passionate obsession and the madness of art.

There’s certainly plenty of room for such a presentation. It could replace the Villa’s dreary inaugural exhibition, which is the disappointment of the debut.

“Plato in L.A.: Contemporary Artists’ Visions” is one of those shows that end up doing the opposite of what was planned. It turns out that Plato, the classical Greek philosopher and founder of the Academy, is of next to no pressing concern for artists working today.

That’s not to say some don’t read him, as philosophically minded artists like Adrian Piper and Joseph Kosuth do. It’s not that the concept of Plato’s allegory of the cave, with its shadowy mysteries of reality and representation, were not important to an artist such as Mike Kelley, whose marvelous 1985 cave drawing is here.

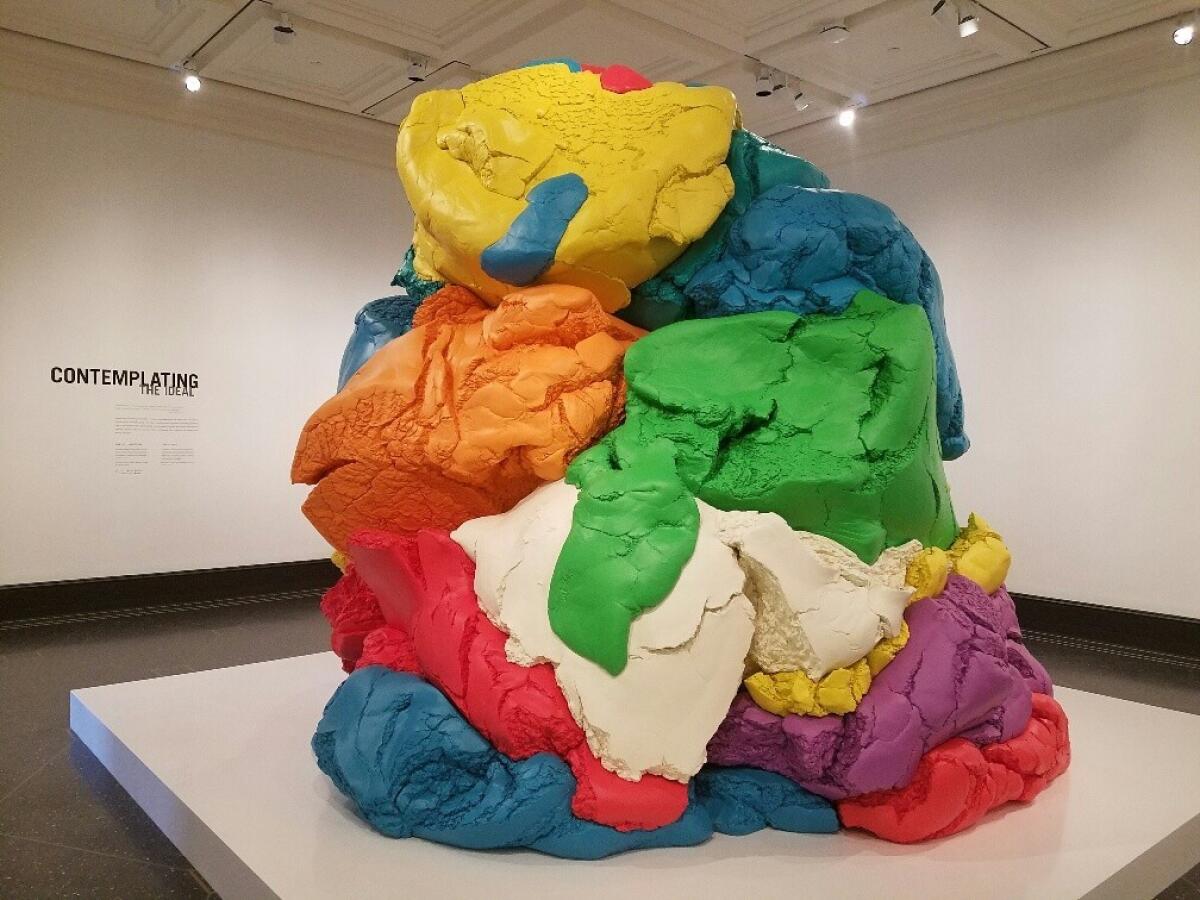

And then there is Jeff Koons’ big, colorful pile of modeling compound, “Play-Doh.” It’s at least a pretty good pun lampooning the Platonic contemplation of ideal form in today’s art.

Yet, Plato, as a foundational figure in Western thought, can be traced as ancestor to just about anything. The show feels flimsy and forced. The effect is further heightened by guest curator Donatien Grau’s decision to invite new works to be made specially for the show by six of the 11 artists. That’s one sure-fire way to guarantee that contemporary artists engage with and respond to Plato’s ideas.

The handsome, well-considered reinstallation of the permanent collection, on the other hand, marks a significant turning point. Before, the collection was displayed according to thematic categories, such as the concept of heroism as an aspirational social good or the diverse roles women played in ancient life. Now, social history has been replaced by art history.

In general, Greek art is on the first floor, Roman art on the second. Galleries unfold the historical evolution of classical art. Side trips are made to the Iberian Peninsula and modern-day Iran and Afghanistan, depending on what’s available in the collection.

The “Statue of a Victorious Youth” — the famous Getty bronze, one of the greatest classical sculptures in the United States — is no longer in an isolation chamber. Now it is installed with other objects of its period, 300-100 BC, including a magnificent marble head of Alexander the Great. Both look smashing, the brilliance of one amplifying the other.

One room is reserved for long-term loans — currently, funerary portrait sculptures from Palmyra, the ancient caravan city that has been so tragically marred by the ongoing Syrian civil war. They will be on view for at least a year, borrowed from the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. The highly individualized Palmyran portraits display naturalistic Greco-Roman elements merged with lavish Persian stylization, a testament to the cosmopolitan character of a wealthy oasis on a developing trade route.

Artistic crosscurrents like that are also a focal point of “Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World,” a 2,000-year survey of Egypt’s interactions with the entire Mediterranean region, organized by Getty director Potts and antiquities curator Jeffrey Spier and on view at the main museum in Brentwood. (If you have a hankering to see an authentic 6th century BC kouros, the sumptuous show includes one from Athens’ National Archaeological Museum.) Plainly the exhibition has been timed to magnify the unveiling of the re-conceived Villa: Where else in the Western U.S. is the depth and breadth of ancient art on such abundant display?

The fashion in museum permanent collection displays in recent decades has been to put social history ahead of art history. Two goals seemed paramount.

One was an apparent belief that art is simply too arcane a matter for general audiences — whom museums crave — while the lived experience of social history might make art more relatable. Everyone can understand religious yearning or relationships between mothers and daughters, right?

The other function was to disguise weaknesses in a collection — say, late-Roman art, poorly represented at the Getty. A thematic focus on gods or daily life could hide it.

The Getty Villa does a U-turn on that — and I’m glad to see it. Ancient art is the centerpiece. The antiquities collection is what it is, and often it’s marvelous. The savvy reinstallation represents a step forward in the museum’s confidence.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Getty Villa

Where: 17985 Pacific Coast Highway, Pacific Palisades

When: Closed Tuesdays

Information: (310) 440-7300, www.getty.edu

christopher.knight@latimes.com

MORE REVIEWS:

Teotihuacan: An ancient Mexican city's remarkable art comes to life

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.