What the sexual harassment allegations at Artforum reveal about who holds the power in art (hint: not women)

- Share via

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published a bombshell essay in ARTnews magazine titled, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

The piece examined this commonplace question, along with its negative implications.

“First we must ask ourselves who is formulating these ‘questions,’” wrote Nochlin, “and then, what purposes such formulations may serve.”

She then proceeded to dismember the question’s premise point by well-argued point.

Art wasn’t just some miraculous channeling of artistic endowment, she noted. It was a skill — “learned or worked out, either through teaching, apprenticeship or a long period of individual experimentation.” Yet, throughout history, women have regularly been denied access to these types of mentoring relationships.

For centuries, women were also prohibited from studying nudes — a foundational aspect of Western art. “As late as 1893, ‘lady’ students were not admitted to life drawing at the Royal Academy in London,” Nochlin wrote, “and even when they were, after that date, the model had to be ‘partially draped.’”

When they did paint, she noted, the activity was derided as entertainment for upper-class women who wanted to cultivate a cultured aspect — a.k.a. “lady painters” — accepted by society because it was a pursuit that was “quiet and disturbs no one.”

Art, in other words, doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It exists within the power structures of society — structures dominated by men. If women weren’t considered “great,” it wasn’t for lack of potential. It was because an entire system was designed to keep them from becoming so.

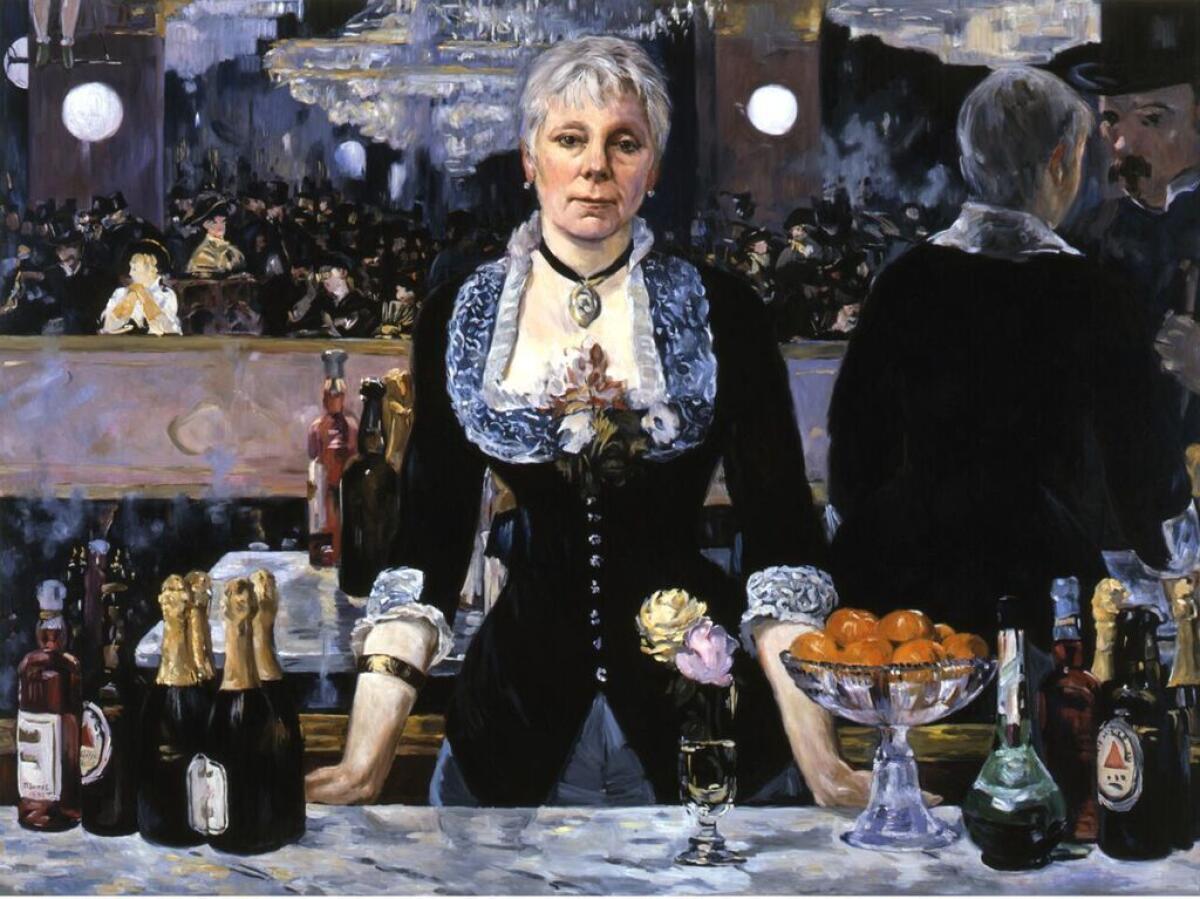

Nochlin died Sunday at age 86 after a years-long struggle with cancer. (Her death was confirmed to The Times by her granddaughter, filmmaker Julia Trotta.) But Nochlin’s seminal essay lives on, discussed in art schools, distributed in feminist theory courses, its text feverishly passed along from one generation to the next. Nochlin was so influential that a number of female artists painted her portrait over the years, including New York-based Kathleen Gilje (who, with Nochlin’s collaboration, inserted her into a well-known canvas by Edouard Manet, looking fierce rather than resigned, like Manet’s original figure). To this day, her essay reminds us that what materializes on any given canvas is a product of unseen institutional forces that benefit some more than others.

“Most men, despite lip-service to equality, are reluctant to give up this ‘natural’ order of things in which their advantages are so great,” she wrote. “For women, the case is further complicated by the fact that … unlike other oppressed groups or castes, men demand of her not only submission but unqualified affection as well.”

Nochlin’s work could not be more relevant.

On Oct. 24, Rachel Corbett of Artnet broke the news that Knight Landesman, one of four publishers at the powerful art industry bible Artforum, had been ordered to seek therapy in wake of allegations of sexual harassment.

In an emailed statement to Artnet, Landesman said, “I have never willfully or intentionally harmed anyone. However, I am fully engaged in seeking help to ensure that my behavior with both friends and colleagues is above reproach in the future.”

Artforum, in a statement posted to the magazine’s website, stated that it took the complaints “very seriously” but called them “unfounded.”

A day later, however, curator Amanda Schmitt, who worked at Artforum from 2009 to 2012, filed suit in the State Supreme Court of New York, alleging that Landesman had sexually harassed her while she was an employee of the magazine and then for many years after.

In the suit, she claims that he subjected her to unwanted touching of her “hips, shoulders, buttocks, hands and neck.”

She also entered into evidence in her suit correspondence that Landesman had sent her, including emails of a very explicit nature and a text message that featured an image of a man spanking a woman thrown over his knee.

Included in the suit are the testimonies of eight additional women, among them two who worked at Artforum, alleging that Landesman harassed them to varying degrees. In the lawsuit, Schmitt contends that Artforum was aware of Landesman’s behavior and did little to stop it.

Shortly after the lawsuit was filed, Landesman resigned and the magazine followed up with a more contrite statement: “We will use this opportunity to transform Artforum into a place of transparency, equity and with zero tolerance for sexual harassment of any kind. Regretfully, this behavior undermines the feminist ideals we have long strived to stand for.”

Since then, five additional women have come forward with allegations of sexual harassment; the magazine’s editor in chief, Mi-chelle Kuo, has resigned (“In light of the troubling allegations surrounding one of our publishers,” she stated in an email to ARTnews, “I could no longer serve as a public representative of Art-forum”); and more than 50 staff members of all genders and across departments — including the magazine’s new editor in chief, David Velasco — have signed an an open letter on Artforum’s website stating that they condemn “the way the allegations against Knight Lan-desman have been handled by our publishers and repudiate the statements that have been issued to represent us so far.”

Landesman could not be reached for comment. And Artforum did not have any additional official pronouncements on the matter.

But Velasco — who by all accounts has been sympathetic to female writers and critics — released a statement to The Times through a publicist: “The art world is misogynist. Art history is misogynist. Also, racist, classist, transphobic, able-ist, homophobic. I will not accept this. I know my colleagues here agree. Intersectional feminism is an ethics near and dear to so many on our staff. Our writers too. This is where we stand. There’s so much to be done. Now, we get back to work.”

By the numbers

As with the many other sexual misconduct accusations working their way through the news — whether about Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, film director James Toback, or former New Republic literary editor Leon Wieseltier — the Artforum allegations have laid bare the art world’s power structures and the inequities women face within them.

Women, for example, hold 48% of museum directorships, but that number drops precipitously as the budget grows, according to a study published in the spring by the Assn. of Art Museum Directors. Only three women run museums with annual budgets of more than $15 million — one of them is Ann Philbin at L.A.’s Hammer Museum. And those same female directors, note the report’s authors, “earned 75 cents on average for every dollar earned by male directors.”

A report published in ARTnews in 2016 found that women at top U.S. institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the

“If we believed that women had equally important things to say, we would give attention to their work that is equal to the guys,” says Los Angeles artist Micol Hebron, who has also been a contributor to Artforum. “If we think of the number of female students that have consistently increased since the inception of MFA programs, the rise of women artists should be much greater than it has been.”

For four years, Hebron has led an art project called “Gallery Tally” that tracks the representation of women in commercial galleries. By her estimates, only three women have gallery representation for every seven men.

Hebron has also been watching how those numbers play out on the media front, particularly in Artforum, the most prestigious of the art magazine bunch.

Like a mirror to the art world it serves, Artforum has an embedded gender inequity. Though the magazine has had female editors in chief, as well as a number of women in key editorial roles, three of the four publishers before Landesman left were male. And its most prized feature — the cover — is dominated by men.

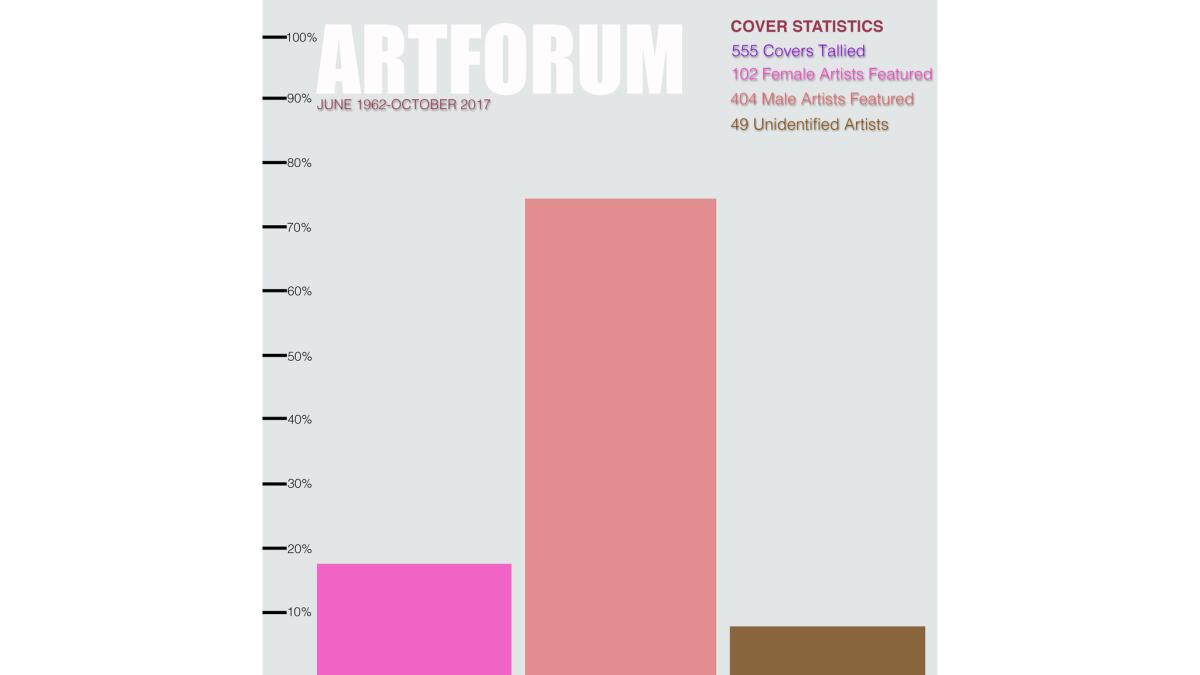

In 2015, Hebron did an analysis of Artforum covers by gender. Since the magazine’s founding, only 18% of covers have gone to women. And there have been many years in which no women have made the cover at all — most recently in 2001.

Artforum, which was founded in 1962 in San Francisco, relocated to L.A. in 1965 and moved to New York City two years later, has been a chronicler of Modernism, minimalism, conceptual art and performance.

“It’s the ‘intellectual organ’ of the international art industry,” says New York-based artist and writer Mira Schor. “It has a distinguished critical history. And as such, it is important.”

If we believed that women had equally important things to say, we would give attention to their work that is equal to the guys.

— Micol Hebron, artist

In its pages, the magazine has leaned toward coverage of conceptualists and international art stars, with less attention devoted to issues such as feminist art and social practice. But that doesn’t mean Artforum hasn’t featured essays by important theorists such as Rosalind Krauss and Lucy Lippard — as well as Nochlin herself.

Schor, a member of the ground-breaking Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts in the 1970s, has contributed important writings on subjects such as painter Ida Applebroog and the Guerrilla Girls, an activist artist collective that has long drawn attention to issues of gender inequity in the art world.

In 2013, Schor says Art- forum’s editors asked her to examine the legacies of Robert Hughes and Hilton Kramer — two of art history’s more testosterone-addled critics.

“That was an interesting thing,” she says. “I would not have expected to be the gatekeeper, the obituary writer for two major male art critics. But in their invitation to me, they stressed two things: that the culture wars of the ’80s and ’90s, in which those figures were significant actors, were for me lived histories, and because of what they considered my ‘independence of mind.’”

But as much as Artforum is the art world’s version of the New York Review of Books, it is also its Vogue — a place to measure power and status. Artforum’s cover and its glossy advertising — the latter of which critic Jerry Saltz has referred to as “the porn of the art world” — tell you more about who’s hot and who’s not than any one article.

Lack of ego?

Certainly, Artforum’s cover statistics have improved in recent years. Women now regularly make up roughly four out 10 covers. But the magazine still has its ups and downs. Only in one year — 1992 — have more women been featured than men. In 2017, only one woman has so far gotten a cover to herself: German painter Kerstin Brätsch. (Artist Jennifer Allora shared the May cover with her partner, Guillermo Calzadilla — they work collectively as the duo Allora & Calzadilla.)

Hebron says this is evidence of a “deep-seated and systemic bias that is continued evidence of undervaluing women in society — and it’s not just in art, but in society in general.”

In a 2015 talk at Art Basel Hong Kong, Artforum co-publisher Charles Guarino (a colleague of Landesman’s) responded to a query about the art world boys club by noting that the magazine had a strong presence of women in its editorial ranks, among its other departments. But to that thought he also added the following observation:

“A lot of women aren’t going to like this, but from experience, I can tell you that anyone capable of doing another kind of work usually does; to be an artist, you need a really serious case of attention deficit disorder, a little bit of Asperger’s, and you need what I can only describe as a man-sized ego.”

Why are there no great female artists? A lack of ego, he surmises.

“The most depressing thing about all of this is that it shows that nothing has changed,” says Schor. “There are more women with power, there are many great women artists, there are brilliant writers, but there is some mechanism that doesn’t change.”

The allegations against Landesman have brought those mechanisms to light. (Among her accusations, Schmitt claims in her lawsuit that “Landesman focused his harassment on young women at the start of their careers who were economically and professionally vulnerable.”)

There are more women with power, there are many great women artists, there are brilliant writers, but there is some mechanism that doesn’t change.

— Mira Schor, artist and writer

As of Monday morning, more than 4,000 female art professionals from all over the world had signed their names to a searing open letter that was published Sunday night in the Guardian (and now visible at its own website not-surprised.org). Among the signatories are Hammer chief curator Connie Butler, photographer Cindy Sherman, artist and critic Coco Fusco and USC art professor Amelia Jones.

“The resignation of one publisher from one high-profile magazine does not solve the larger, more insidious problem,” the letter states, of “an art world that upholds inherited power structures at the cost of ethical behavior. Similar abuses occur frequently and on a large scale within this industry. We have been silenced, ostracized, pathologized, dismissed as ‘overreacting,’ and threatened when we have tried to expose sexually and emotionally abusive behavior.

“We will be silenced no longer.”

Solving this inequity, in other words, will take more than a lawsuit or a few public pronouncements. And it is about much more than Artforum. It is about reconceiving the systems in which artists live, work and think.

Perhaps Nochlin, in her conclusion, said it best:

“Using as a vantage point their situation as underdogs in the realm of grandeur, and outsiders in that of ideology, women can reveal institutional and intellectual weaknesses in general, and, at the same time that they destroy false consciousness, take part in the creation of institutions in which clear thought — and true greatness — are challenges open to anyone, man or woman, courageous enough to take the necessary risk, the leap into the unknown.”

It’s time for that leap.

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

18%: Artist Micol Hebron tallies the presence of women on Artforum covers

Beyond Harvey Weinstein: 30 other high-profile men accused of sexual misconduct, related behavior

Female lawmakers, staffers and lobbyists speak out on 'pervasive' harassment in California's Capitol

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.