What to see in L.A. galleries: World War II farm labor camp photography and more

- Share via

The first of many dark ironies to emerge in the quietly devastating exhibition "Uprooted" at the Japanese American National Museum surfaces right near the entrance. A reproduction of a 1942 sugar company ad pictures an internment camp above an all-caps appeal that says, "You don’t need to wait any longer to get out.”

The ad lists seven reasons why evacuees newly forced by Executive Order 9066 to live in barracks behind barbed wire should apply to work in lower-security farm labor camps: Earn money! Make new friends! Support the war effort! Patriotism and profit — ever the best of allies.

More than 33,000 Japanese Americans opted to be placed on farms throughout Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, Montana and other states, filling in for workers called away by the war. Mostly, they harvested sugar beets, a crop used for food but also, significantly, in the production of munitions and synthetic rubber. At the same time, the Farm Security Administration had to find labor to fill in for those same Japanese Americans on the 6,000 farms along the Pacific coast that they were ordered to abandon.

The FSA also employed a now legendary team of photographers, who chronicled rural poverty and small town life, legitimizing government aid programs and illustrating their success. Russell Lee, one of the agency's stalwarts, made roughly 600 pictures of the euphemistically named "relocation" effort: pre-evacuation preparations and fire sales, ID-tagged children and armed guards at the assembly centers. (It's uncertain whether this body of work was self-motivated or made on assignment; FSA photographs commonly blur that distinction.)

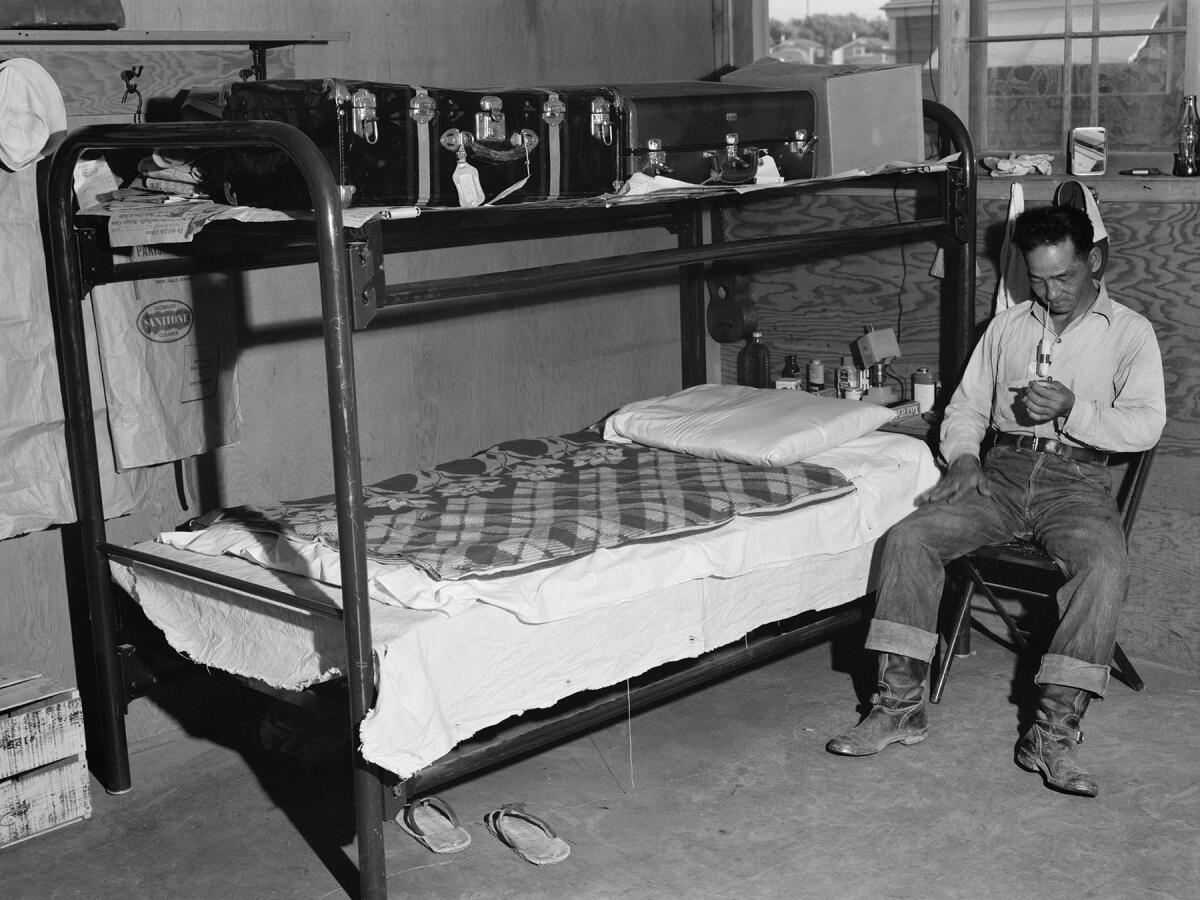

Little-known within Lee's extensive body of work are his images of the bitter slice of history told in "Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps During World War II." The show, organized by the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission, features 45 of the black and white photographs Lee shot in the summer of 1942 in Idaho and Oregon. With methodical clarity (Lee's boss at the FSA called him "a taxonomist with a camera"), they portray key aspects of camp life: the stoop labor, living spaces within the tents, how laundry and cooking were done, how the workers spent their leisure time.

Lee was deeply troubled by the situation and was compelled to document the injustice, but as with evidentiary pictures as a class, his can't simultaneously reveal both a problem and its solution. Accompanying text bolsters the visual information, and in a thoughtful move, organizers of the show chose to provide both the original, insistently neutral FSA captions together with more fleshed-out, editorial commentary. A photograph of lunches being prepared for workers in the field bears not only the original, straightforward descriptive label but also the additional note that the milk included in the pails often spoiled in the heat by lunchtime.

What Lee does best in these photographs — and what offers the most tangible clue to his motives — is render his subjects with respect, upholding their dignity in the face of indignity. Through tender, telling details of place and action, he humanizes those who have been systematically dehumanized, individualizing those wrongly assigned collective guilt. His work presents an honorable — urgent, even — model in these days of inflammatory rhetoric against Muslims, rumors of imposing a registry based on religion and the invocation of Executive Order 9066 as historical precedent for the government to strip immigrants of their basic rights.

Japanese American National Museum, 100 N. Central Ave., Los Angeles. Through Jan. 8; closed Mondays. (213) 625-0414, www.janm.org

The words that reflexively come to mind before Sharon Ellis' extraordinary work could use some customizing. Yes, she is a visionary but even more so a visionist, an apostle for sight, for observation as an active, acute, transformational practice.

The scenes she paints suggest the supernatural , but since they are very much rooted in this world, they might better be described as super-natural. They represent not another reality but this one — amplified and intensified.

There's ample time to muse over such fine distinctions while in thrall to her dozen recent works at Christopher Grimes Gallery. This is Ellis' first show of paintings on paper, and a difference in texture registers first of all. Instead of the deep gloss of layered alkyd on prepared canvas, the paint here soaks into the tooth of the paper and reads in places as feathery, like colored pencil. The paintings are about 12 inches by 16 inches, modest in size compared with her typical works on canvas. Though intimate, they conjure a vastness of emotional or spiritual scope independent of their scale.

Ellis, based in Yucca Valley, taps into both the wild energy of nature and its mathematical order. In "Firefly Fugue," silhouetted reeds in ecstatic dance frame an efflorescence of luminous sparks. The two halves of the painting closely mirror each other, a lattice of harmonious symmetry, while the whole buzzes in unfettered, electric lime.

Ellis channels Agnes Pelton in the softer heat of "Endless Summer," and throughout, her articulation of earthly rhythms and reverberations echoes Charles Burchfield. Caspar David Friedrich is another of her aesthetic mentors, as is William Blake. Ellis, like them, operates from a state of wonder, from the radiant place where nature, self and spirit converge. Her work calls for a new term uniting the visual and visceral.

Christopher Grimes Gallery, 916 Colorado Blvd., Santa Monica. Through Jan. 7; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 587-3373, www.cgrimes.com

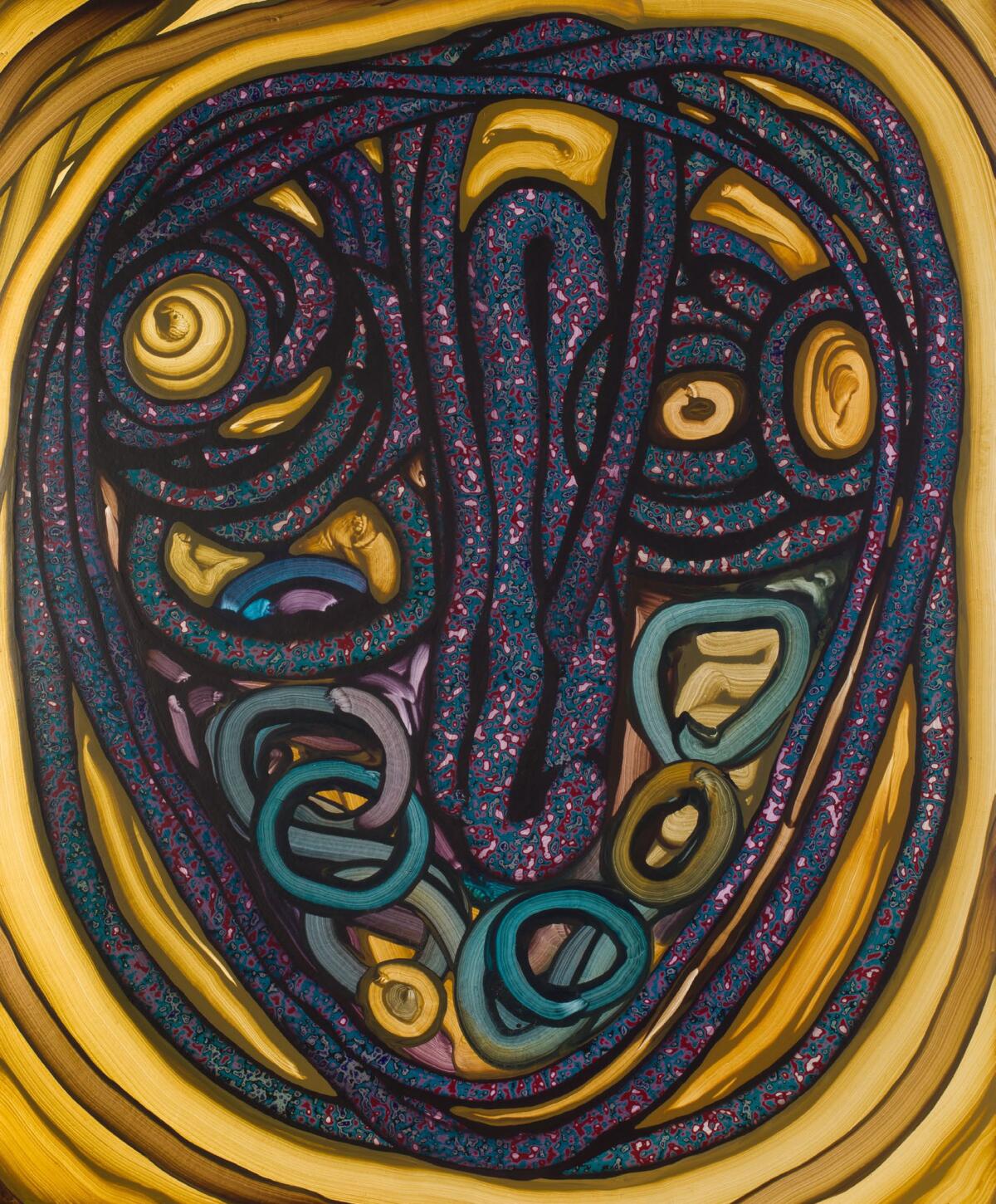

Nathan Redwood's invigorating show at Jaus might loosely be called an extended meditation on the portrait.

Head and shoulders can be discerned in most of the 45 paintings on paper (all 30 inches by 22 inches and hung in a grid), but distinguishing characteristics of identity are beside the point. The portrait format serves largely as a vehicle, a scaffold upon which Redwood, an extraordinarily agile, athletic painter, climbs and swings with abandon.

Each image doubles as an insistent inquiry into the capacity of paint to conjure space and imply motion, to act out possibilities. The mood overall is one of exuberant restlessness, ingenuity and irrepressibility.

Redwood's basic unit of expression is the line, a vigorous, translucent, tubular thing that runs both slim and fat, can constitute both figure and ground, and has formidable momentum either way.

In one particularly goofy piece (all are untitled), Redwood, now based in L.A. and Arizona, builds a face out of extruded metal-gray line. The eyes and nose, fashioned as if from crudely coiled piles of soft matter, pop out cartoonishly. In another painting, this one broodingly elegant, ribbony tresses of Prussian blue accrete into head and shoulders, surrounded by squirming streaks of blood red.

The physicality of this work falls somewhere between lavish and lascivious. Light seems to travel through Redwood's looped, dragged, taffy-stretched line, animating an already rapturous palette of teal, ocher, emerald and brick. In a few pieces, Redwood pulls away layers of paint and in others, he builds up the pigment with modeling paste. He mixes oil with both enamel and acrylic to evoke a delicious range of textures.

Five paintings on canvas here present a similarly rich materiality. The ropes of layered and abraded color in "Not a Mask" resemble the gorgeous mottled-gem surfaces of Ken Price. Through oblique reference or stylistic nod, Van Gogh, Jasper Johns and Edvard Munch have a presence here, too. Independent curator Carl Berg organized this show, Redwood's first solo appearance in L.A. since 2010. Quite an exhilarating return.

Jaus, 11851 La Grange Ave., Los Angeles. Through Jan. 15; open Saturdays and by appointment. (424) 248-0781, www.jausart.com

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Times art critic Christopher Knight’s latest reviews

Times theater critic Charles McNulty’s latest reviews

Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne’s latest columns

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.