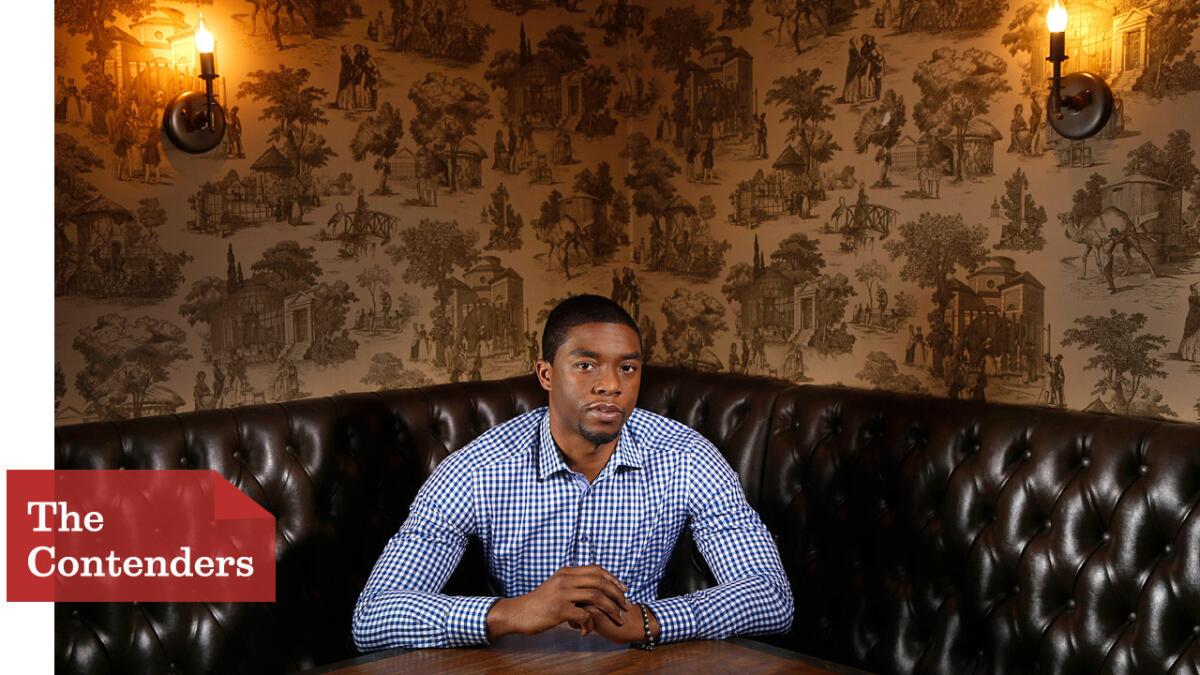

The Envelope: Chadwick Boseman learns James Brown’s moves and motivations

- Share via

Chadwick Boseman hit it out of the park last year with his quietly riveting performance as Jackie Robinson breaking baseball’s color barrier in “42.” This year he’s back as another legend, James Brown in Tate Taylor’s “Get On Up.” The quiet is all gone: His Brown is a tower of power. With a wink — often directly at the audience — the Godfather of Soul’s brilliance and demons fight it out for control.

Fighting off a cold after a press trip to open the film in Paris, London, Berlin and Zurich, Boseman nurses a cup of tea and considers his future. He recently sold a movie pitch to Universal that he is writing and will star in, but can’t yet talk about. And despite his coy disavowal when questioned directly, Boseman has since been revealed as Marvel’s choice to play Black Panther, the first black superhero to get his own film. Sounds a bit like the hardest working man in show business.

“Get On Up” cuts back and forth among different ages, completely out of order. Did you at least shoot it chronologically?

No. There was a day where I was 55, 17 and then 35.

How did you prepare for such an expansive role?

In terms of really focused study, I began to read whatever was said about his childhood. And at the same time, I was listening to as much music as I could and watching footage, but that’s too daunting. You’re absorbing it, and it will affect you later on when you understand certain things. But the thing I could focus on was: I don’t know anything about this little boy.

That child so informs the story.

It’s the thing that’s constant. It might be a different wife, it might be different band members, but the only constants are [band mate] Bobby Byrd and the little boy. And even Bobby Byrd is gone at certain points. … There’s a sense of abandonment that he has, and, in the young boy, there’s a sense of sadness and solitude. But being out there and having that imagination enabled him to make music. When he gets older, it does turn into loneliness. I think that’s the core. “I’m going to make people need me so that I don’t have to worry about being alone.”

He even directly engages the audience at times. What was it like looking right into the camera?

It was weird. You spend so much time learning to not look at the camera. It was a convention that Tate felt would be important to the film, and people didn’t understand it at first. When I first read it, I thought, “Oh, no, that’s got to go. That’s going to be hard as hell.” But then I saw what he was doing and I was, like, “Oh, this could be really cool. You have to at least try it and then cut it out if it doesn’t work.”

How much time did you spend rehearsing James Brown’s dance moves?

We had two months. Five days a week, about five hours a day. But honestly that is not enough time to learn how to dance like James Brown. You’re basically patting your head and rubbing your stomach at the same time, while sliding across the floor. I would have to rehearse while we were shooting. We’d do 12-, 14-hour days, and then I’d have to rehearse at night. [Choreographer Aakomon Jones] would be, like, your bottom is good but you need to work on your top. So I would set up mirrors so that they would be up here on top and down here, but nothing in the middle, so I could isolate and watch what’s happening with each part.

Was there a hardest scene or age to play?

They were all difficult first off, but there was a scene in the end with Viola Davis — it was such an emotional scene. She is a powerhouse actress. Tate changed the scene the night before because it didn’t quite work. We came in the next day and had this whole new scene, so it was difficult because of that and also because it was him dealing with his mother after all those years. The depth of that is crazy. And to me, he turns into the little boy in that scene.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.