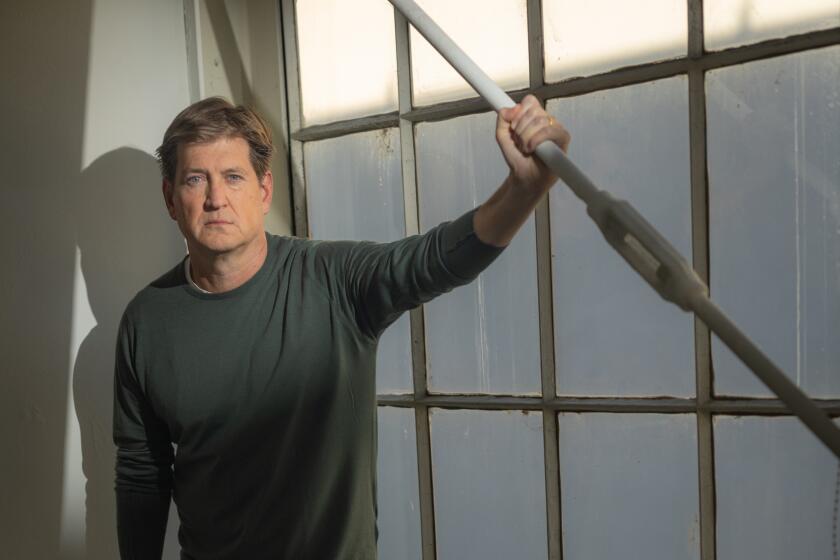

Robert deMaine’s sobering journey to be L.A. Phil’s principal cellist

His new home was filled with moving boxes, and much of the furniture was still missing in action, but Robert deMaine had the air of someone who has finally settled down.

“I apologize for the mess,” the cellist said, while showing a reporter through the clutter of a three-story townhouse in South Pasadena where he recently moved with his wife and two children.

Passing through the garage, he pointed to a sporty red coupe and said, “That was my gift to myself when I got tenure.”

As the recently appointed principal cellist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, deMaine, has had a lot to celebrate in recent months. The 44-year-old musician joined the orchestra in early 2013 and was granted tenure shortly thereafter. It’s the biggest job of a career that has also included first chair at the Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

The new home, a rental that is the family’s second since moving to Southern California, is another point of pride.

On Thursday, he’ll be a soloist with the L.A. Philharmonic in a performance of Brahms’ Double Concerto at the Hollywood Bowl. (Violinist Hilary Hahn has withdrawn from the concert due to an inflamed muscle and will be placed by Alina Pogostkina.)

“I feel like I’ve earned the sunshine,” he said about L.A. “We really want to put down roots here.”

The cellist took his family to Disneyland not too long ago. “It’s a colossal rip-off, but I would do it again,” he said.

In an interview at the family’s dining table, deMaine spoke at length about the ups and downs of his career. There have been some notable downs to balance out the recent ups.

He discussed the Detroit Symphony’s labor strike that began in 2010 and lasted several months. He also volunteered and spoke frankly about his past battles with alcohol and how his addiction nearly ended his music career in his late 20s.

“I’m an alcoholic — a recovering alcoholic. I haven’t had a drink in 15 years. It’s 15, right, hon?” he called to his wife, Betsy, who was in the kitchen. The couple met six months after deMaine became sober.

“1999! That’s right, 15!” she called back.

DeMaine has an upbeat demeanor that he brings to his work — though he said he is also capable of putting his foot down when necessary.

He described his job as principal cellist as being an “immediate connection to the music director” for his section.

“I’m trying to absorb all of his body language and in a way become his or her extension from the platform,” he explained. “That tends to be very contagious within the section. Some principal players tend to move around more than others — in my case, considerably more.”

The position — which was previously held by Peter Stumpf, who stepped down in 2012 — also entails administrative responsibility, including artistic issues, like bowings, and personnel matters.

DeMaine described bowings as something that is “very important to coordinate among sections,” and said it involves not only making sure that his section is unified, but also that the bowings produce the desired sound for the piece.

The orchestra declined to say if any current cellists with the L.A. Philharmonic auditioned for the first chair position. The final choice was made by music director Gustavo Dudamel, based on candidates who had been advanced by a panel that didn’t include any members of the orchestra’s administration.

DeMaine recalled that in Detroit, he had to put out some personnel-related fires.

“They were disciplinary things. I’ll just leave it at that,” he said before adding that one incident required him to “look two disputing colleagues in the eye across the table of the union and say, ‘You both need to shape up.’”

He said the 2010 strike in Detroit was a big reason he started looking for another job. A dispute over compensation and other factors kept musicians out of the concert hall for six months, one of the lengthiest strikes in U.S. orchestral history.

“I loved that orchestra — it was under the gun financially a lot more than L.A,” deMaine said. “But we weren’t eager to leave. There weren’t skid marks on our driveway.”

He added that he wasn’t directly involved in labor negotiations: “I don’t have much of a head for numbers.” Instead, the cellist used the strike as an opportunity to more fully pursue his solo and chamber music career.

He is a member of Ehnes Quartet and the recently formed Dicterow-deMaine-Biegel Trio, which features violinist Glenn Dicterow, who stepped down this season as the concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic.

DeMaine said that one of his weaknesses is collecting expensive cellos. Many of them are still housed with his in-laws in Michigan, but he recently acquired an expensive instrument with Venetian origins.

“This is my new baby,” he said, lifting the cello from a bed in the ground floor guest room. He said he paid less than top dollar for the instrument because the instrument’s parts have mixed provenance. “The whole is the less than some of its parts. It’s crazy how these things work.”

A native of Oklahoma City, deMaine started playing the cello at the age of 4. His mother and eldest sister had both studied the cello; his father was an Army veteran.

“The cello and baseball were my two loves. I was a catcher,” he recalled. As a teenager, he quit the cello for a number of months, preferring “to grow my hair long and play in a band.”

But he eventually returned to classical music and started winning competitions. After studying at a number of schools, including Yale University, he landed a spot at the Hartford Symphony in Connecticut.

It was during his period in Hartford that his drinking reached a crisis level.

“I had a lot of struggles with stage nerves,” he said. “It got so bad that I could not play the cello without being inebriated. My nerves were that bad.”

He recalled a particularly harrowing incident: “I can’t tell you which city or orchestra it was... but I was scheduled to play the Dvorak Cello Concerto with a very good orchestra… I just had not prepared adequately. And I got to the dress rehearsal... and I just had a meltdown. I had a meltdown in front of 100 people on stage.

“That one particular memory haunts me, and it haunts me almost every day of my life,” he said.

After failed stints in rehab and detox, he hit rock bottom in his late 20s. “I’m not a deeply religious person,” he said, but “when I finally quit, it was like the hand of God held me. It was an epiphany... even though my body was broken.”

He met his future wife Betsy, who was playing French horn at the Hartford Symphony, six months later. They now have two children in grade school.

DeMaine credited his wife for putting her music career temporarily on hold to organize the family’s move to L.A. “I really couldn’t have done it without her,” he said.

The cellist added that his successful fight with the bottle acted as a career motivator.

“I felt like I wasted a decade of my life,” he said. “It’s a potent fuel for self-improvement… I more than made up for it in my 30s and I’m still pushing.”

In the end, “people are forgiving,” deMaine said. “If you do pull your life together, I think they reward that.”

Twitter: @DavidNgLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.