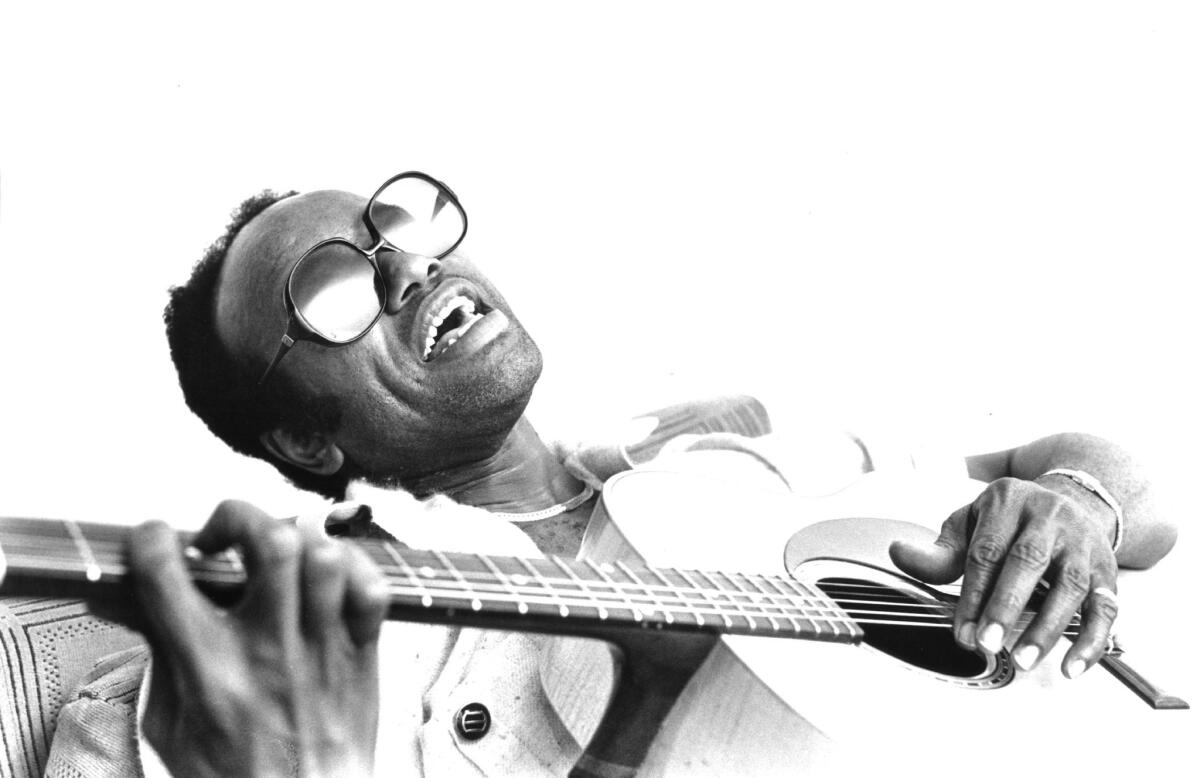

Critic’s Notebook: Appreciation: Bobby Womack, soul legend, guitarist, L.A. connector

The connections are endlessly surprising, those that Bobby Womack forged during a 60-year career that transcended genre, border and race. The singer, songwriter, guitarist and longtime Los Angeles resident, who died Friday at age 70, was the center of a web as intricate and miraculous as his best songs and guitar lines.

After all, few can claim to have toured with soul legend Sam Cooke, yelled at the Who’s Keith Moon for bouncing on Womack’s new couch, learned of friend Jimi Hendrix’s death through Janis Joplin, traded songs with Keith Richards and Ron Wood in Topanga Canyon, or rolled through L.A. in limousines at the peak of his success.

Get comfortable and maybe pop on Womack’s greatest songs: “Communication,” “Who’s Foolin’ Who,” “Lookin’ for a Love” (made famous by the J. Geils Band) or “Harry Hippie.” There’s so much more.

Starting in the early ‘60s, he learned to nail his guitar cues while on a multi-act tour with musical taskmaster James Brown. He married Cooke’s widow a few months after Cooke was killed and decades later appeared on the breakout pop-rap album by Gorillaz. Two years ago he released “The Bravest Man in the Universe,” an album as inventive as anything in his storied career.

A creative force who didn’t stop working even when he was struggling with substance abuse and, later in his life, cancer, Womack is perhaps best known for writing “It’s All Over Now,” the classic kiss-off made famous by a rising British Invasion band, the Rolling Stones. “She put me out, it was a pity how I cried. Tables turn and now it’s her turn to cry,” sang a sassy Mick Jagger. “Because I used to love her, but it’s all over now.”

Womack was a professional musician before he hit puberty, one of five brothers who traveled the Midwest gospel circuit with their father starting in the early 1950s. His path carried him across the country by the time he could vote, alongside singers who would achieve greater fame, but no more impressive an output.

“We were all on the stage with Sam Cooke and Lou Rawls, all of the guys,” Candi Staton told me about her youth on the road with lifelong friend Womack, with whom she collaborated.

As part of the Jewell Gospel Trio with her sister in the early 1950s, recalled Staton, she spent long hours with Womack and his brothers, playing ball before shows, eating meals and attending church, where she and Bobby sat together and giggled through service. “The older people would say, ‘Shhh! Be quiet!’ And that would make us more tickled,” Staton said.

As he grew, Womack caused a rift in the family when he announced his desire to abandon spiritual music, following his friend Cooke onto the R&B charts as his guitarist.

It was a key moment in Womack’s career, Staton said. “His brother wanted to go one way, and he wanted to go another way. The Bobby I know? He thought, ‘Y’all got it. I’m out of here. I can make it on my own.’ And he did, and he made it big.”

After spending time in Memphis working in the studio of famed producer Chips Moman on records by Elvis Presley (“Suspicious Minds”), the Box Tops, Dusty Springfield, Aretha Franklin and others, Womack returned to Los Angeles to continue hawking his songs.

While there and embracing a lifestyle made possible through Rolling Stones royalty checks, he landed in the studio with a young Janis Joplin, who was looking to fill her album “Pearl.”

Recalled Womack to writer Harvey Kubernik of that first session pitching songs to Joplin: “She said, ‘When I push the button that means I like it. If I don’t push the button then you gotta quit and go to another song.’ So as soon as I hit the first song, ‘Trust Me,’ she pushed the button.”

The biggest of his hits was also one of his best, a gritty song called “Across 110th St.,” about the boundary between Harlem and Central Park. Featuring a brand of hard soul that helped propel the funk movement, the song featured brass, congas, a fleet of strings and Womack’s urgent voice offering lyrics about class division in New York City.

Womack also helped craft one of American music’s greatest achievements, Sly & the Family Stone’s “There’s a Riot Goin’ On.” Along with Ike Turner, Billy Preston, Rosemary Stewart (Rose Stone) and others, Womack helped Sly Stone build a stunning, labyrinthine soul classic.

Staton recalled those as being heady times with Womack. “We used to hang out in his Rolls-Royce,” she said, laughing. “We were all over L.A. He and [the Tempations’] David Ruffin and I would be everywhere. We’d stay out all night.”

On “The Poet” and “The Poet II” (one of the first R&B sequel albums), Womack helped bridge ‘70s analog funk with the newly available compact synthesizers to experiment with new tones. Those records sound even more vital now than when they were released in the early ‘80s.

Such contributions to music and culture can’t be overstated. Womack was a key figure for so long that whole chunks of his influence can fall by the wayside when faced with outlining it.

He did struggle, though. His work later in the ‘80s was marred by drug abuse, and by the ‘90s hip-hop had overtaken R&B, even while the nascent genre sampled Womack’s work.

But he endured, cleaned up, and kept doing what he loved. Central to it all was Womack’s creative spirit, which eagerly embraced the songwriter’s chief mission, one that transcends record sales, arguments on the secular and spiritual or appearances on Rolling Stone covers.

“Nobody can sing ‘Sweet Caroline’ like that,’’ stressed Staton about Womack’s hit take on Neil Diamond’s classic. “Bobby was just the greatest. He had such a unique voice that nobody could imitate. One of a kind.”

As Womack told Kubernik, “What separates everything is the music that reached peoples’ hearts and the stories that will live on forever. And they are being told over and over again.”

Follow Randall Roberts on Twitter: @liledit

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.