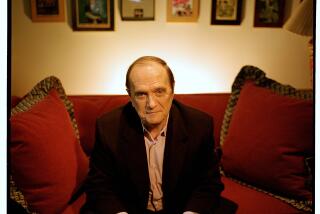

From the Archives: Bob Hope, the master of the one-liner, dies at 100

- Share via

This article was originally published July 29, 2003.

Bob Hope, the elder statesman of comedy whose extraordinary career spanned vaudeville, Broadway, radio, television, movies, books and makeshift concert platforms in war zones, has died. He was 100. Hope died at 9:28 p.m. Sunday at his home in Toluca Lake of complications from pneumonia, his publicist, Ward Grant, announced Monday. His wife, Dolores, and other members of his family were at his bedside when he died.

An increasingly frail Hope marked his 100th birthday quietly on May 29 with well-wishing from the famous and not so famous from around the globe. Hope’s home was inundated with birthday cards and flowers. An intimate party attended by close family members was held with cake and a 100-candle celebration.

President Bush led the nation in mourning Monday for the beloved comedian, saying, “The nation has lost a great citizen.”

“Bob Hope served our nation when he went to battlefields to entertain thousands of troops from different generations,” the president told reporters before boarding Air Force One at Andrews Air Force Base. “We extend our prayers to his family. God bless his soul.”

Bush also issued a proclamation ordering all U.S. flags on government buildings lowered to half-staff on the day of Hope’s funeral.

One of the world’s most enduring comedians, “Rapid Robert” outlasted hundreds of briefly popular political satirists, social-comment comics and television sitcom stars who flared and faded.

From his early days in radio to the television specials that would endear him to subsequent generations, Hope became synonymous with the comedy monologue, striving to be topical but not offensive, cocksure but not arrogant.

“He possessed all the gifts I, and all other comedians, could ever ask for or want,” “Tonight Show” host Jay Leno said in a statement Monday: “impeccable comic timing, an encyclopedic memory of jokes, and an effortless ability with quips. His monologues — which were always so topical — had an enormous influence on me. In fact, they established the paradigm for me, and for all of us in this business. We are all blessed to have had him as our standard-bearer.”

With his wisecracking manner and trademark sneer, Hope was the quintessential populist comedian, his humor fueled by the legions of joke writers for whom he was a tough boss.

“He had such a strong comic persona that all the writers got to know it,” said Gene Perret, who began writing jokes for Hope in 1969. “It was a confidence that bordered on arrogance. Hope could always boast about himself, but it [would] normally turn itself around where he’s the brunt of the joke.”

“If they had coed dorms when I went to school, you know what I’d be today?” Hope once quipped. “A sophomore.”

Presidents, too, were a favorite target of his humor, including Gerald R. Ford, a golfing buddy known for his erratic play. Hope once joked that there were “86 golf courses in Palm Springs, and Jerry Ford never knows which one he’s going to play until his second shot.”

Hope was a friend of, and honored by, presidents for more than 50 years starting with Franklin D. Roosevelt, and he was an acquaintance and occasional golf partner of celebrities around the globe.

His face was known to millions of Americans spanning three generations, perhaps especially those who served in the military during World War II and the Korean and Vietnam wars.

The comedian began entertaining servicemen and women at U.S. bases in 1941—starting at California’s March Field near Riverside — and in 1948 began annual Christmas shows at American bases overseas.

Hope was never a member of the military. But on Oct. 29, 1997, when he was 94, he became the first American designated by Congress as an “honorary veteran of the United States Armed Forces.”

Hope appeared for the presentation in the Capitol Rotunda looking, as one observer noted, “as fragile as a sparrow’s egg.” Many thought his visit to the Capitol would be the increasingly deaf and weak comedian’s final public appearance.

And it was just eight months later that he was mourned on the floor of the House of Representatives. Then-Rep. Bob Stump (R-Ariz.), working from an erroneous release of a prewritten Associated Press obituary on the Internet, rose to announce that Hope had died. Tributes to the comedian followed from other congressmen, but at his home, Hope was having the last laugh.

“They were wrong, weren’t they?” Hope told friends who called to offer condolences to his family.

Half a Century of Entertaining Troops

His shows for the troops — with an entourage of other comics, singers, dancers and pretty girls — lasted for half a century, often not far from the fighting, earning Hope praise for his patriotic efforts and criticism for his hawkish stance during the Vietnam War.

He once said — either exaggerating for effect or on the level — that he had traveled almost 10 million air miles entertaining American service personnel around the world. He ended his regular Christmas shows in 1972 during the difficult days of the Vietnam War.

The hiatus lasted 11 years. In 1983, at 80, Hope once more hit the road, this time traveling to Lebanon, where a peacekeeping force of U.S. Marines and ships of the 6th Fleet had gathered to attempt, without success, to stem the internal bloodshed in Beirut.

The comedian entertained first aboard the naval ships off the coast and then, to everyone’s surprise, went ashore to give the Marines his special brand of humor. He got out a scant 30 minutes before the compound at which he appeared came under shell fire.

“If this is peace,” Hope asked the cheering troops, “aren’t you glad you’re not in a war? I was told not to fraternize with the enemy, and I won’t ... as soon as I figure out who it is.”

In 1990, the octogenarian Hope was in the Middle East cheering troops in Operation Desert Shield and then Operation Desert Storm, the first U.S.-led campaigns against Saddam Hussein.

Queen Elizabeth II recognized the native Briton’s entertainment of British troops during World War II by granting him a knighthood. His official title was Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

“Seventy years of ad lib material and I am speechless,” Hope said from his Palm Springs home when the knighthood was announced by British Prime Minister Tony Blair during an official visit to Washington in February 1998. The knighthood was officially presented at the British Embassy in Washington on May 17, 1998, shortly before Hope’s 95th birthday.

Periodic charges, especially during the turbulent 1960s, that he was a “war lover” stung Hope, and he once fired back in uncharacteristic public anger: “How can anyone who has seen war, who has seen our young men die, who has seen them in hospitals, possibly love war? War stinks!”

Even after the wars ended, Hope continued visiting veterans hospitals, as if to underscore his concern for those who served in the American military.

He also continued a hectic pace of personal appearances across the United States, often booked a year in advance at colleges, universities, conventions and charity shows.

Donated and Raised Millions of Dollars

His own contributions to charities, either donated through the Dolores and Bob Hope Foundation or raised through free performances, amounted to millions of dollars. He donated 80 acres for the Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, and raised money over the years for its expansion and operation.

Dolores Hope, whom he married in 1934, managed their donations, and even she declined to estimate how many millions her husband had given or raised for charity. But she did say most of it involved young people—in hospitals or colleges and universities.

The multimillionaire (Hope’s fortune has been estimated at as much as $500 million) had oil wells in Texas, was once part-owner of the Cleveland Indians baseball team and had a variety of other business ventures under Bob Hope Enterprises. But most of his money was in property.

He was thought to have owned about 8,500 acres in California, most of it in the San Fernando Valley, bought when it was fruit orchards and vacant lots.

By his own estimate, he was one of the largest individual property owners, if not the largest, in the Golden State.

He was able to reach that status, he said, when he and crony Bing Crosby — neither of whom knew anything about oil wells — invested in one in 1949 that produced oil.

“It was a fluke,” he said once, “but a good one. I took the money and bought land.”

He disliked talking about his wealth. Once, just before a tour of Vietnam, he was asked if it was true that he was worth $50 million. Hope snapped back, “If I had $50 million, I wouldn’t go to Vietnam; I’d send for it.”

He was born Leslie Townes Hope on May 29, 1903, in Eltham, England, the son of stonemason William Henry Hope and Avis Townes Hope, a former concert singer.

He was the fifth of seven brothers, and when he was 4 his family moved to Cleveland, where he attended grade school. (“I was an all-around student. I flunked everything.”) He became a U.S. citizen in 1920. After high school, Hope tried various jobs — including boxing under the name Packy East — and then began dance lessons. He was a natural.

At 19, he was teaching dance classes, and two years later he was booked by Fatty Arbuckle into a show called “Hurley’s Jolly Follies.” It was the beginning.

Hope sang, danced, did comedy bits and doubled on the saxophone, an experience, he reminisced years later, that gave him the poise that was his trademark in stand-up comedy.

From “Follies,” he went on to vaudeville in Detroit and then to a part in the show “The Sidewalks of New York.” After it folded in 1927, Hope, until then not a soloist or comedy specialist, discovered that he was both.

He had a dance act with partner George Byrne, and they were doing a vaudeville show in New Castle, Ind. Hope was asked to introduce the next week’s act, a Scot named Marshall Walker, and he did so with humor.

“I know Marshall well. He saves everything. He got married in his backyard so the chickens would get the rice. He had a sunstroke playing golf and counted it.”

The audience loved it, and Hope became a solo act. He went back to Cleveland for a year to develop the comedy style that varied little over the years — topical one-liners fired with a pixie leer — and then tried to sell it in Chicago.

Hard Times for Struggling Performer

They weren’t easy times. He lived mostly on coffee and doughnuts and once got by on a nickel’s worth of beans a day for four weeks, an experience he recalled later when he was making up to $50,000 for an hour’s performance.

“I was in debt and had holes in my shoes,” he said. “When a friend bought me a steak, I’d forgotten whether to cut it with a knife or drink it from a glass.”

Finally, through a friend, Hope was booked into Chicago’s Stratford Theatre for three days—a booking that stretched into six months. He was a smash.

From there, it was back to New York and Broadway. There was “Ballyhoo” in 1932, but the show that ultimately put Hope on the trail to international stardom was Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach’s “Roberta” the next year.

Then he was invited to appear on “The Rudy Vallee Show,” a radio network variety program, and that was followed by other guest appearances even as Hope performed on Broadway in “Ziegfeld Follies of 1936,” in which he introduced the standard “I Can’t Get Started,” and “Red, Hot and Blue!” in which he and Ethel Merman sang “It’s De-Lovely.”

He appeared in “Smiles” in 1938.

That was Hope’s breakout year. Pepsodent gave him his own radio show, which began his six-decade association with NBC, and he made his feature film debut in “The Big Broadcast of 1938.”

“Big Broadcast” more than anything else elevated the comedian to stardom and gave him his theme song, the Academy Award-winning “Thanks for the Memory,” which he had sung in the movie.

He really hit his stride in movies with 1939’s horror comedy “The Cat and the Canary.”

“I turned into box office,” Hope told The Times in 1991. “When ‘Cat and Canary’ came out, [people] started running into the theaters. Then Paramount came to my dressing room with a contract for seven years. So I signed for seven years.”

Hope kept the NBC radio show for 18 years, and his guest stars read like a who’s who of the entertainment world: Al Jolson, Jimmy Durante, Eddie Cantor, Tallulah Bankhead, Bette Davis, Red Skelton, Fibber McGee and Molly, Lum and Abner, Amos and Andy.

A Lasting Friendship With Bing Crosby

He met Crosby playing golf, a game both loved almost as much as entertaining, and invited him to appear on his radio show.

A lasting friendship grew, barbed in public and warm in private. Crosby gave Hope the name “Ski Snoot,” and Hope liked to needle Crosby about his wealth by saying, “Bing doesn’t pay income tax. He just calls the government and says, ‘How much do you boys need?’ ”

They turned their mock feuds and personal friendship into a winning combination in seven road films, beginning in 1940 with “Road to Singapore” and ending in 1962 with “Road to Hong Kong.”

In all of the “Road” films, they played two carefree buddies out to make it big but invariably running into trouble. Always along for the fun was actress Dorothy Lamour, who played the object of their affections. The best-loved of the series was 1942’s “Road to Morocco.”

Hope was devastated when Crosby died of a massive heart attack while playing golf in Spain in October 1977 and, for one of the few times in his career, canceled a performance.

Hope made 58 movies in all, including such classics as “The Ghost Breakers,” “The Paleface,” “Monsieur Beaucaire” and “Fancy Pants.” He even went dramatic with good results as Eddie Foy Sr. in 1955’s “The Seven Little Foys” and as the colorful New York mayor Jimmy Walker in 1957’s “Beau James.”

He made several films with good friend Lucille Ball, including 1949’s “Sorrowful Jones,” 1950’s “Fancy Pants,” 1963’s “Critic’s Choice” and 1960’s “The Facts of Life,” which was nominated for several Oscars.

Although he never won an Oscar for acting (“At home, we think of Oscar week as Passover”), he was honored four times by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for his contributions to the world of entertainment. He also received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 1959. He began emceeing the Oscars in 1940, and for years hosted the televised Academy Award presentations, opening his first in 1953 with the line “Television. That’s where movies go when they die.” His final turn hosting the program came in 1978, the 50th anniversary of the awards. In all, he hosted or co-hosted the Academy Award show 18 times.

“Maybe Bob never won a competitive Oscar, but he won the hearts of the members of the Academy, the governors of the Academy and the hundreds of millions who watched the Academy Awards presentations,” Frank Pierson, the president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, said in a statement Monday.

Hope began his television career on Easter in 1950. He had a weekly program from 1955 to 1964, and hosted 285 highly rated specials. He made guest appearances on many other shows.

“Bob Hope: The First 90 Years,” his three-hour birthday special in 1993, included Johnny Carson in his first public appearance since retiring from “The Tonight Show” and featured one of the last hurrahs for George Burns, who died in 1996 at the age of 100. Hope still had the power to pull 25% of the nation’s Friday night TV audience, and the show won the Emmy for outstanding special.

In ads after his final special in 1996, “Bob Hope ... Laughing With the Presidents,” he formally and amicably ended his association with NBC, declaring himself “a free agent.”

Was Author or Coauthor of 10 Books

In addition to his screen career, 10 books of humor or autobiography were either written or co-written under Hope’s name.

His first book, “They Got Me Covered,” was designed as a marketing tool for Pepsodent, which was then the sponsor of Hope’s radio program, and Paramount Pictures. The cost of the 95-page paperback was 10 cents and a box top from a tube of Pepsodent, which paid for the book’s printing. Paramount helped promote it to tie in with the Hope movie “Nothing but the Truth,” which was just being released.

The book sold 3 million copies.

While he was building a career, Hope was also busy raising a family. He had married singer Dolores Reade while he was appearing in “Roberta” on Broadway. She survives him as do their four children, sons Anthony and Kelly, daughter Linda Hope and Nora Somers, and four grandchildren.

Funeral services will be private for immediate family members only. Public memorial services are being planned.

In lieu of flowers, the family suggests that masses or donations be made to the Bob and Dolores Hope Charitable Foundation, Toluca Lake, Calif. 91602.

Homes at Toluca Lake and Palm Springs

He moved to Toluca Lake in 1938 and maintained his home and office on the six-acre site, although in 1979 he also built a multimillion-dollar estate in Palm Springs.

Until his final years, Hope was almost constantly on the road, playing shows and benefits in the United States and on military bases in far-flung corners of the Earth. He gave five command performances in London and two shows in the Soviet Union. “I appreciated the Russians’ 21-gun salute,” he said. “I just wished they’d waited until the plane had landed.”

He televised one show from China and marveled: “They have 900 million people, and none of them know who I am.”

Honors were heaped on Hope throughout his career. The Guinness Book of World Records cited him as the most honored and publicly praised entertainer in history, with more than 2,000 awards.

Among his citations were a Medal of Merit from President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Congressional Gold Medal from President John F. Kennedy (he was only the third civilian to be so honored), the Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon B. Johnson, the National Medal of the Arts from President Bill Clinton, the George C. Marshall Award, the Navy’s Distinguished Service Medal and the Distinguished Public Service Medal of the U.S. Department of Defense, the highest award the military can bestow on a civilian. The Air Force named a C-17 transport jet for him. And in 1998 he was awarded a papal knighthood by Pope John Paul II.

Schools, streets and plazas have been dedicated in Hope’s honor. In addition to the honorary Oscars and the Emmy, he won radio’s Peabody Award and in 1975 was initiated into the Entertainment Hall of Fame. In 1985, he was given a lifetime achievement award from the Kennedy Center.

Hope could, and did, joke about all of the honors he received (they filled two warehouses) because he couldn’t resist a funny line. He said once: “I’ve got so many doctorates, I’m beginning to resent Medicare.”

In 1967, when he became the first honorary member of Harvard University’s Hasty Pudding Theatrical Society, he told a packed house:

“I’ve been given a medal by my country for leaving it, an Oscar in a year when I didn’t make any movies, and a B’nai B’rith Award for being a Gentile.”

But he never took any of the awards lightly, saying once that it was not so much the receiver that mattered, but the giver. “What’s important is not what an award means to me, but what it means to them.”

His Toluca Lake office was filled with mementos ranging from a 9-foot replica of an Oscar to a doll handed to him by a child at an airport. He had a dollar bill from comedian Jack Benny and a silver set from the queen of England, along with trophies, plaques, medals, silver cups, keys to cities, state declarations from around the world, military patches, autographed artifacts from global leaders and celebrities, and thousands of photographs.

When he turned 95, the comedian donated his personal papers, recordings of radio and television broadcasts, prints of movies, scripts, photographs, posters and 100,000 jokes to the Library of Congress, along with several million dollars to preserve the collection.

Considered a political conservative, Hope was still one of the first comedians to take aim at Sen. Joseph McCarthy during the red-baiting days of the 1950s. He also maintained a warm friendship with the nation’s Democratic presidents, especially Kennedy, whose sense of style and wit he greatly admired, and with Harry S. Truman.

The entertainer was proud that Truman kept under the glass on his Oval Office desk the one-word telegram Hope had sent him when, against all odds, Truman won election in 1948 over Republican Thomas Dewey. The telegram said: “Unpack.”

Hope continued his friendship with Richard Nixon even after the president resigned in disgrace, and the comedian was a Palm Springs neighbor and frequent golf partner of Ford. But Ronald Reagan, the former actor, was his special friend, and Reagan was prominent in a three-hour television special that saluted Hope’s 80th birthday in 1983.

Golf was more than a hobby or pastime with Hope. He liked to say it was his vocation and comedy his avocation. A golf club was often his prop on stage, and golf clubs filled his Toluca Lake home.

His Bob Hope Chrysler Classic in Palm Springs, an annual golf tournament that began in 1960 under a different name and took Hope’s name in 1965, has raised tens of millions of dollars for charity.

Agonized Over Time Away From ChildrenBut more than golf, Hope loved his family, and in private he would agonize about the years on the road that kept him away while his children were growing up.

Once, during a private interview, as he sat by a window overlooking his lush gardens in Toluca Lake, he reminisced about how the children would sit at the dining room table as he read his radio routines, with wife Dolores, a devout Catholic, admonishing him when his jokes were too risque for family consumption.

“I learned to temper my humor in those years,” he said. “I discovered which jokes were for matinees and which ones for the night crowds in Vegas. Dolores was a tough critic.”

“He was gone a lot and we missed him, of course,” Dolores Hope said, “but we always had quality instead of quantity.... When he wasn’t home, he’d call almost every day, except when he was in a combat zone. Even then, he’d try.”

Theirs was a happy marriage, she once said, and she would not have traded it for anything. “We are normal, imperfect people trying to be perfect. We have been blessed with humor and with a respect for each other,” she said.

Then she added with a smile: “If it hadn’t been a good marriage, I’d have never stayed.”

Despite the reports of his many infidelities over the years, she was a patient but not docile wife to the hyperactive comedian. When they were together, he often deferred to her.

Once, aboard an airplane to St. Louis, she responded tartly to a churlish comment by her husband: “Let’s try that tone of voice again!”

“Dolores takes care of me,” Hope often said, and as a result he watched his diet, slept well and exercised, keeping himself fit and trim.

Actress Eva Marie Saint, who appeared with Hope in two movies, “That Certain Feeling” and his last feature, “Cancel My Reservation,” credited his wife with being a stabilizing influence in his life.

“He took care of himself and he was very disciplined,” Saint told The Times on Monday. “I think the fact that he had this lovely talented lady beside him, Dolores, added to his longevity. They were so supportive of each other and, my goodness, wouldn’t you have to be understanding to be married to someone who loved being on the road and just enjoyed working?”

Into his 60s, after personal appearances, sometime as late as 2 a.m., Hope would walk, a habit that worried his aides when they were playing crime-plagued cities.

To placate them, he sometimes carried a golf club with him, and the comedian striding through the predawn streets of towns across America became a familiar sight.

He was able to make occasional public appearances well into his 90s.

He made a special appearance on the Emmy telecast in September 1998 and earned a strong ovation from the Academy. The next month, he and Dolores showed up at a black-tie tribute to Rosemary Clooney.

As for his children, they would voice wistfulness at the father they never quite knew well enough.

In a profile of Hope by John Lahr in the New Yorker in 1998, his daughter Linda, who ran Hope’s production company, noted: “I don’t feel that I really know him. That’s a kind of sadness for me because I would have liked to know him better.”

Hope, by almost all measures, was an up person; his attitude was positive, his enthusiasm immense. His rare flashes of public anger were usually aimed at those who questioned his motives.

Asked once if his charity donations or performances were simply a way to beat the tax man, the comedian flared. “Hell no!” he said. “I do it because it gives me pleasure! I’ve been doing it for years. Benny and [Milton] Berle and I used to play benefits on Broadway Sunday night.

“Giving is a joy when you’re lucky enough and healthy enough to do it. In fact, it’s a ... privilege!”

At times, the comedian had as many as 13 writers working for him, and into the 1990s he employed three full time — along with four secretaries, a publicist, a business manager-agent, an accountant and household staffs at his Toluca Lake and Palm Springs homes.

Hope’s file of jokes, kept in two large vaults, was immense, and covered everything from apples to zebras. The material fed not only his shows, but also his books and for many years a column for the Hearst newspaper chain.

More than 100 filing cabinet drawers were filled with one-liners and sketches, jokes numbering in the millions — and there were those who thought that Hope, even in his later years, kept them all in his head.

During a one-hour show, he would use about 150 jokes and, except for television, never used cue cards. He constantly updated his material to suit the social and political climate of the day and the city or country in which he was performing.

Jokes came not only from his writers but also from friends and caddies, hotel bellmen and fans. “There’s a straight line lying around in everyone’s head,” Hope liked to say. “All you’ve got to do is reach in and lift it.”

As he grew older, he admittedly mellowed in his style and slowed slightly in the pace of his delivery, realizing that he didn’t have to hammer a joke home anymore: “The audience and I know each other now. We’ve built up a relationship.”

Even so, he never ceased updating and refining his material or watching the front rows to see who was laughing and who wasn’t.

Hope’s mastery of audiences never lessened over the years.

In an interview with Playboy Magazine in 1973, Hope was asked the secret of his comedy.

“Material has a lot to do with it, but the real secret is timing,” Hope replied. “Not just of comedy but of life. It starts with life. Think of sports, even sex. Timing is the essence of life and definitely of comedy. There’s a chemistry of timing between a comedian and an audience. If the chemistry is great, it’s developed through the handling of the material, and the timing of it — how you get into the audience’s head.”

“The great ad-libbers are the ones with the best timing, like Don Rickles.... Timing shows more in ad-libs than anything else.”

For his part, Rickles, who was on many of Hope’s specials in the 1960s, recalled working with Hope as a lot of fun.

“He was also congenial but a real technician,” Rickles told the Los Angeles Times on Monday. “When we did sketches they had to be exactly the way he thought of it. Of course, he was always right.”

Hope called his success luck but couldn’t help adding: “The harder I work, the luckier I get.” His favorite joke, he used to say, was one on former President Ford: “I played golf with Ford today. He had a birdie, an eagle, an elk, a moose and a Mason.”

And while older generations of Hope’s fans stayed loyal to the end, over time a gap developed with younger audiences who might have been mystified at his enduring attraction.

In the biography “Bob Hope: A Life in Comedy,” late night show host Conan O’Brien reflects on that gap.

“I don’t think a lot of people in my generation saw his best work ...” O’Brien told author William Robert Faith. “If you go back and look at his movies ... like “Son of Paleface” or any of the Road movies, you’re just amazed at his talent. He was so smooth and so precise.”

O’Brien also noted that Hope’s character development in these films was also unique.

“I think he was the first guy to master the fast-talking coward, the cowardly wise guy, the one who has a lot of bravado but when the tough guy sneaks up behind him, he’s suddenly saying, ‘Oh you’ve been working out, haven’t you?’ ”

As fate would have it, Hope lived longer than all his great contemporaries — George Burns, Lucille Ball, Bing Crosby, Milton Berle and Jack Benny. He even lived longer than the congressman who announced his death prematurely on the floor of the House. He died Sunday on the 50th anniversary of the armistice that ended the Korean War.

For his 100th birthday in May, NBC aired a two-hour special called “100 Years of Hope and Humor,” which did well in the ratings and has been nominated for an Emmy.

On Sunday night, family members as well as longtime caregivers and a priest gathered at his Toluca Lake home as the comedian slipped away.

“I can’t tell you how beautiful and serene and peaceful it was,” his daughter Linda told a news conference Monday. “The fact that there was a little audience gathered around, even though it was family, I think warmed Dad’s heart.”

“He really left us with a smile on his face and no last words.... He gave us each a kiss and that was it,” she said.

MSNBC, co-owned by his longtime employer NBC, first broke the news of his death Monday morning.

Approachable by Public and Press

For all his fame, he was approachable by both public and press, arranging interviews during busy schedules and never turning away a request for an autograph.

But it was during the war years that the indefatigable comic made himself the most available — to the men and women on the fighting fronts and to the wounded in military hospitals.

Novelist John Steinbeck, writing for the New York Herald Tribune in 1943, described a Hope visit to a hospital during World War II:

“Probably the most difficult, the most tearing thing of all is to be funny in a hospital.... In the long aisles of pain the men lie, with their eyes turned inward on themselves....

“Bob Hope and his company come into this quiet, inward, lonesome place, gently pull the minds outward and catch the interest, and finally bring laughter up out of the black water.”

Steinbeck wrote about the efforts of Frances Langford to sing in one hospital and how, when one of the wounded soldiers began to cry, she broke down and couldn’t go on.

“Then Hope walked into the aisle between the beds, and he said seriously: ‘Fellows, the folks at home are having a terrible time about eggs. They can’t get any powdered eggs at all. They’ve got to use the old-fashioned kind you break open.’

“There’s a man for you,” Steinbeck concluded. “There is really a man.”

Times staff writers Paul Brownfield and Susan King contributed to this report.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.