The long, strange odyssey of bringing Oscar fave ‘Toni Erdmann’ to the screen

- Share via

Reporting from New York — Directors can use all kinds of tricks to get actors in the shooting spirit.

But the upstart German filmmaker Maren Ade employed an especially unconventional technique in greeting the stars of her new picture “Toni Erdmann” for the Romanian portion of production.

Ade showed up at the down-on-its-heels Bucharest airport as an over-the-top character — tricked out as a goofball mogul, pouring Champagne wearing bathroom slippers in the back of a white stretch limo.

“It was a little embarrassing,” the writer-director, 40, recalled in an interview about her sophomore feature. “I mean, me, there, like this” — she leaned back swaggeringly and mimed smoking a cigar — “did shock the actors and get them off-balance. But I’m not an actress — as I’m sitting there, I’m wondering, ‘What am I doing?’ Then we’re driving through these poor neighborhoods in this limo and I’m thinking, ‘This is all a little tacky.’”

Bucharest’s pain, though, may be moviedom’s gain.

A flair for both the human and the absurd animates “Toni Erdmann,” a German-language tragicomedy that is one of the most surprising and lauded films of the year. The movie joins “Boyhood” and a rare handful of modern pieces in capturing the well-meaning fumble that can occur when parents and children try to connect.

But while centering on the relationship between a shaggy elderly jokester and his uptight adult daughter, “Toni Erdmann” also manages a thematic juggling act. A film about oppositional family dynamics ends up as an inquiry into much more, with feminism, globalism and corporate culture all falling under its gaze. American movies tend to be about either very big stakes or very intimate relationships. “Toni Erdmann” pulls off both at once.

“I wanted to look at worlds coming together — Eastern and Western Europe, women and a male-dominated corporate culture,” said Ade of her movie, which came out to rave reviews Sunday and has been shortlisted for the foreign-language Oscar. “I also wanted to find a way that two family members can use role-playing to start from zero with each other.”

“Toni Erdmann” begins with Winfried and Ines Conradi’s relationship in the small German college town of Aachen but soon heads to Romania, where Ines (Sandra Hülller) works as an oil consultant for a machismo-drenched multinational — and where Winfried (Peter Simonischek) has decided to drop in for a surprise visit. Ines attempts, half-heartedly, to integrate her father into her corporate and social life. (The two are synonymous.) When the weekend ends, she packs him back to Germany.

But Dad has other ideas. Unconvinced his daughter has her life as together as she claims, Winfried surreptitiously stays behind. He then makes his presence felt by assuming the comic persona of “Toni Erdmann” — a supposed “life coach” intent on helping anyone he encounters. Wearing a wig and gag false teeth, he crashes Ines’ social obligations, creating numerous script opportunities for pathos, slapstick and surrealism.

What seemed like effortless mayhem on the screen was the result of a painstaking — and unorthodox — directing approach.

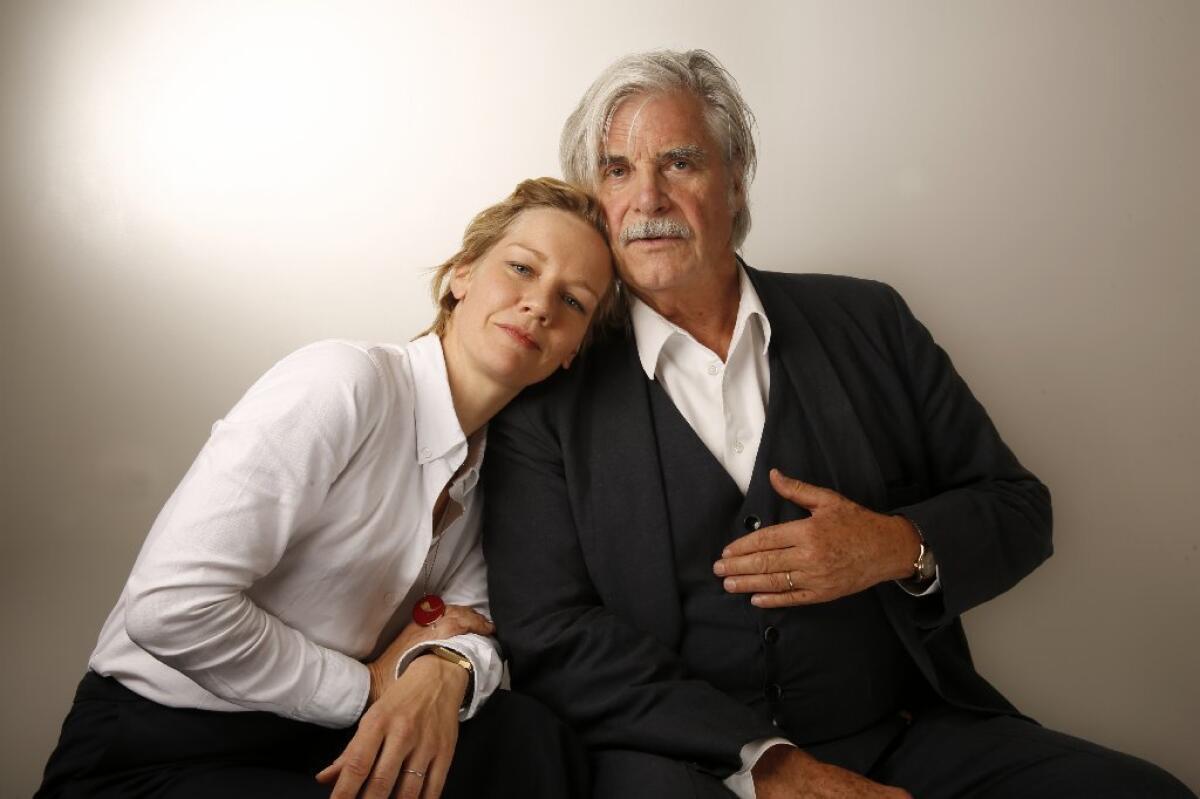

Ade chose actors with extensive theater backgrounds — Simonischek in particular is a member of an Austrian rep company that performs the likes of Chekhov — so they could improvise and build the characters. She then had them rehearse for a year. “I did Shakespeare — Prospero — and I only had three months to prepare,” Simonischek noted dryly as he sat next to Ade.

The director (her last name is pronounced AH-day) tweaked and wrote new scenes as the actors rehearsed. She also employed what might be called Method directing.

The filmmaker, for instance, would stress-test Hüller to see if the actress could maintain her cool and straight face, which she needed for scenes in which Winfried crashes her life as Toni. At one point during production, Ade had a supporting actor play a scene opposite Hüller wearing giant ears without acknowledgment. “I think I made it through 10 minutes without breaking,” Hüller recalled.

Ade also would occasionally behave as though she were living inside the movie, as with the airport-pickup moment, in which her bold limo appearance mimics a move Toni tries in the film.

Simonischek, for his part, would go out into the streets of Bucharest dressed as Toni Erdmann, in part to get into character and in part to gauge how people might react to someone so cluelessly oafish (and OK, maybe in small part to see how much he could pull their legs). “Many people didn’t react,” he said. “But you could see they wanted to react.”

One big set piece involved an awkward “naked party” Ines throws for colleagues that turns into a sideways act of feminist empowerment. The scene was shot over a rather long period of three days (the whole movie was shot over 56, an eternity for an indie production). The scene involved nude people coming in and out — and often standing around the hallways — of a real-life Bucharest building, whose occupants would steal glances through peepholes wondering what in the name of Nadia Comaneci was going on.

Among the film’s many showstoppers is a scene at a Romanian dignitary’s home where Ines turns the tables on Winfried by launching into a karaoke rendition of a Whitney Houston hit. Hüller attempted some smaller versions of the performance, but it wasn’t working.

“I finally just walked over to Sandra and said, ‘Do Vegas,’” Ade recalled. The dozens of extras and crew were startled as Hüller began belting out “The Greatest Love of All” like a female German Wayne Newton.

“I guess that’s really become part of the legend now, hasn’t it,” queried Hüller when told of Ade’s recounting, sounding unsure of whether to feel proud or worried.

Hüller, 38, came of age in Communist East Germany and was both intrigued and baffled by Ines’ appetite for status. She said she even initially had reluctance about taking on the project, although for entirely different reasons.

“I must admit that when I read the script I didn’t really get it. It was too complicated,” the actress, who’s won awards for work in earlier German-language films such as “Requiem,” said over coffee here recently. “The lines just didn’t make me laugh. You read it and you think, ‘Is this supposed to be funny? It just feels invasive.’” Indeed, Ade wasn’t necessarily seeking that mix of hilarity and heartbreak viewers now experience. “I always knew this would work as a drama. I was surprised it worked as a comedy,” she admitted.

But Hüller said her skepticism melted when she began having conversations with Ade. “I met Maren and she told me the very intimate reasons why she wanted to do it. It changed my mind.”

After the festival-circuit success of her first feature, the 2009 romantic drama “Everyone Else,” Ade felt pressure and a stigma. Being a female in a male-dominated profession meant she had to work doubly hard to show she could belong to the club. She decided to research the world of oil consulting and pour her concerns into that; indeed, “Toni Erdmann” can on one level be viewed as a fable about women’s struggles in 21st century entertainment (not to mention, in the clash of Ines’ conglomerate and the Romanian workers left behind, a timely story about the myths of globalism).

But Ade also had more familial reasons fueling her interest. Though her father hasn’t taken on a comic impersonation to insinuate himself into his daughter’s life, he often uses broad humor to relate emotionally. On a trip to the U.S. years ago, Ade picked up a set of gag teeth at an “Austin Powers” premiere and gave it to him; he has since made it part of his in-family shtick.

Those thoughts spurred her to reflect on their own attempts to find common ground and fed a general preoccupation with who we are in relation to our loved ones.

“A family can be an area where it’s hard to escape your status. People achieve a certain role over the years and it becomes stiff,” said the director, who now has young children of her own. “When is it good to break that? Or what happens when one person really wants someone else to break it?”

Simonischek pondered his own experiences as a father.

“I remember when one of my sons was little and I couldn’t be home to read to him before bed. So I would give him a tape of a radio play I did and he could listen to that. I felt so guilty,” the actor recalled. “And on my 70th birthday my sons, who are adults, were there, talking about their experiences with me as a father. One of them thanked me for the tape. I said, ‘You’re not upset I wasn’t home?’ And he said, ‘No! My friends all thought it was cool that my father did a radio play.’”

“That’s what being a parent is, I think,” noted Ade. “You invest and you invest and you invest. And if you’re honest you have to admit you don’t really know what you’re going to get back.”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

On Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

ALSO

Here’s our film and TV predictions for this year’s Golden Globes

Unseen films of 2016 feature Nick Cave, teens and the best use of a Stones track ever

With pluck and verve, Debbie Reynolds represented the best of the great Hollywood tradition

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.