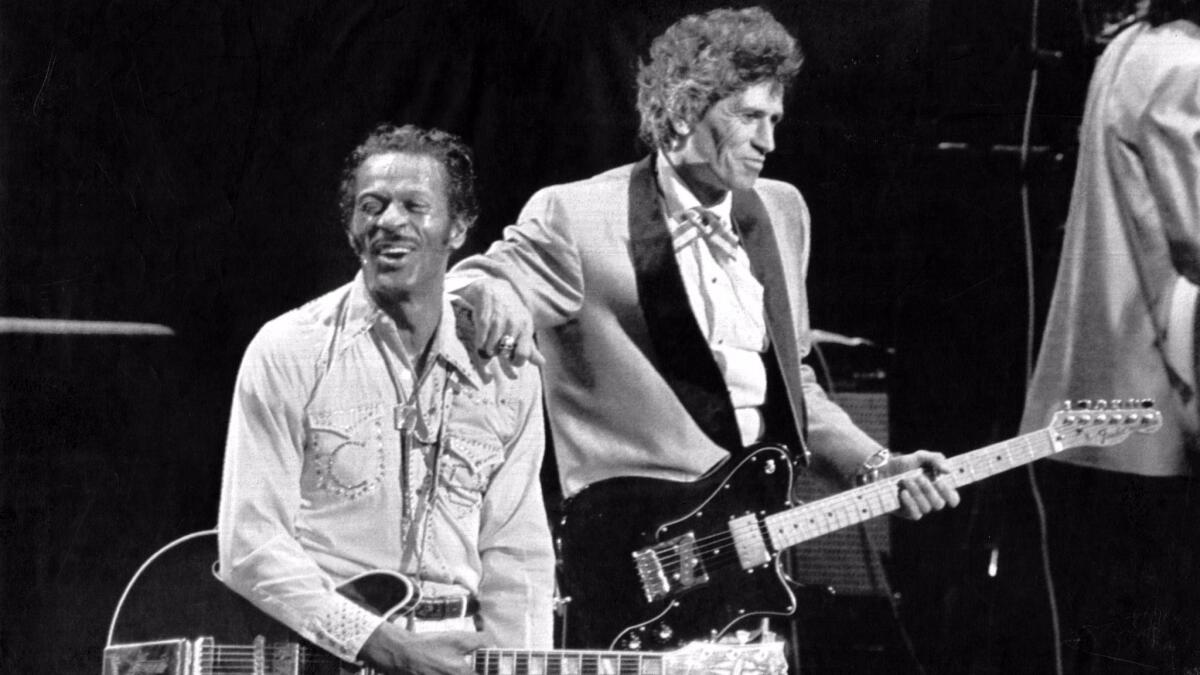

Exclusive: Keith Richards talks Chuck Berry: ‘I’ve learned more and more from him over the years’

- Share via

In trying to capture the momentous influence of Chuck Berry, who died March 18 at age 90, numerous obituaries and appreciations written in recent days have theorized that a number of rock ’n’ roll groups may never have formed were it not for his pioneering work.

But it’s no wild assumption to say that the Rolling Stones might never have existed had it not been for the Berry connection.

Guitarist Keith Richards famously introduced himself to Mick Jagger when they were teenagers who randomly found themselves on the same train in London.

“We happened to get in the same railway carriage together, and Mick was holding two Chess records,” Richards told The Times on Friday, taking time out from a early spring vacation to the Caribbean to discuss the incalculable impact Berry’s music had on him. One of those records in Jagger’s possession was a Berry album, the other was from Chicago blues great Muddy Waters.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

“In those days in England, a carriage held about six people, and for some bizarre reason, I had this one to myself,” Richards said. “Suddenly, the door opened, in popped Mick and immediately, I spied what he’s got under his arm.”

That moment launched a friendship and artistic collaboration that’s lasted 55 years and counting. One of Berry’s most fervent musical disciples, Richards spoke to The Times about his lifelong love affair with Berry’s music and what it has meant not only to him but also to countless musicians who have followed in his wake.

How did Chuck Berry’s music first come onto your radar screen?

I’m sort of wondering if it was “Johnny B. Goode” or “Sweet Little Sixteen.” It was probably pretty much as soon as he recorded them, although it sometimes took a little while for American records to get to England.

Do you recall, as a teenage music fan, what it was that first grabbed you about his music: his guitar work, the groove, his voice or the lyric?

Yes, yes, yes and yes. (He laughs.)

I guess it was the combination of all of those things. To me, it had sort of a crystal clear clarity of what I wanted to hear, and what I was aiming for. In retrospect, it was Chess Records. That studio — it was amazing. [Bassist, songwriter and producer] Willie Dixon was in the band with [pianist] Johnnie Johnson, it was an amazing collection of musicians. And they were having fun — that was the underlying aspect of it all. There was an exuberance and they were not too serious. What was serious was what was going down — they weren’t serious about it (laughs again).

What was the first Chuck Berry song you learned to play?

The first was probably “Sweet Little Sixteen,” since I was about 16, or 15, at the time. There’s that lazy beat and a sweet little melody. After that the one that taught me was “Back in the USA.” The Beatles also learned it (laughs).

Was it Chuck Berry who first made you aware of Chess?

That’s a good question. At my age, in my stage of development at that time, yeah, I wanted to know where records were made, where the guy that made ’em came from. I was into all of that. To me, it was all important to find these sources of sound. That was my mission at the time. My real awareness of Chess Records was from Chuck Berry, but I was also listening to Muddy Waters, and I realized that these guys were working in the same room.... At the time, information was sparse but every little piece was treasured.

Obviously, that made a huge impression on the band, because on your first trip to the U.S. in 1964, you made sure to visit Chess, and record there as well.

We were amazed that that came together, and certainly that that room was available to be used. At the time, it felt like, wow, you think you’ve passed on and gone to heaven.

Is there one Stones song you consider most thoroughly inspired by Chuck’s music?

Oh God, off the top of my head, I would say no, because we deliberately tried not to “do a Chuck Berry,” so to speak. But on every one, Chuck’s influence is there, for sure. And I love the fact that he could vary his music. When you listen to “[You] Never Can Tell,” he had a handle, he was very interested in various kinds of music. He used country music....[and] he was a great admirer of Hank Williams. We used to sit around talking about country writers.

Some cynics have suggested that Chuck wrote only one song and that he just rewrote it over and over again.

They obviously ain’t listening, pal. There are shallow listeners, you know.

But there are some superficial similarities — talk about some of the nuances that differentiate those signature introductions for “Johnny B. Goode,” “Carol” and “Little Queenie”?

I look upon that as sort of a clarion call, his way of saying, “I’m here.” That’s why those famous intros for “Johnny B. Goode,” “Carol” and “Little Queenie” are sort of the same. It was almost his own personal monogram on the damn thing before he would start.

People try and pick out things that are similar. Like Jimmy Reed — you want to talk about a guy who played the same song [repeatedly] and beautifully! It’s not that — it’s the variations on the theme that count. Also the effortless ease of that rhythm he could produce, which everybody else pumps away at. People don’t realize Chuck used his whole body to play that riff, he doesn’t just use his wrists. I’m still working on it.

If you ever saw him in concert, or look at old film footage, you really see how much body language there was in his performances.

Everything was syncopated and synchronized to his body movements. We all know the duck walk — that’s the famous one, and it’s a good one too. But if you look at old footage of him, playing in those times, those early movies, “Jazz on a Summer’s Day,” you see a sort of almost demonic power going on in that rhythm and his delivery of it. It always fascinated me.

You’ve often said it’s the “roll” in “rock ’n’ roll” that is the key thing for you. I was listening to his version of “Route 66” again and noticing how the guitar and piano play a pretty straight rhythm while the bass and drums really swing the beat. The way those things rub up against each other on that record strikes me as a great example of the “roll.”

This is the thing that fascinated us. It was that eight [beats]-to-the-bar against the four-to-the-bar swing feel. It could be produced if you had an upright bass.

When the electric bass came along, what happened is that basically everybody became a guitar player, and usually in the old days, it was the worst guitar player who got the bass. [He chuckles.] Also, [the bassist] automatically played the eight-to-the-bar like a guitar player would. That shifts the whole thing and that also shifts the drummer, because now on the high hat, he’s got different work to do. Then the beat stiffened and it became rock. Before that, the upright bass would swing it and it was basically four to the bar. That was the roll in rock [’n’ roll].

Mick’s statement after Chuck passed had a very interesting line in it that said, “His lyrics shone above others and threw a strange light on the American dream.” What was your awareness of racial tensions in the U.S. before you first came here — did you catch glimpses of it through the records you were hearing?

Only very slightly. Chuck was by then mainly aiming at a white audience, and he didn’t want to rub nobody the wrong way. I’d have to search to find the chip on the shoulder here and there, which he definitely had himself, especially after the jail [time he served on a conviction of transporting a minor across state lines “for immoral purposes”]. He came out another man after that, and I don’t blame him. It took me a while to get past the chip, but we managed.

Speaking of the chip on his shoulder, just about every story on Chuck’s life has mentioned that scene in Taylor Hackford’s 1987 documentary “Chuck Berry Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll” where he reams you about not getting a guitar lick right in one of the songs you’re rehearsing. How do you look back on that exchange now?

At the time, I said, “I’m running this band, I’m going to let Chuck [mess] with me, and I’m going to show the rest of the guys in the band that I don’t give a [damn].” Because he was just playing with me. He’d give me a different riff every time I played it. I could have said, “Actually, I prefer to play it this way.” But I just thought I’d let him wear himself out on me.

When was the last time you got together with him?

The last time I saw Chuck was in Boston [in 2012], he got the [PEN New England’s Song Lyrics of Literary Excellence] award. Apparently, it was the first time they sort of acknowledged that songwriting could possibly be called literature. [He laughs.] Chuck was the first recipient, and I was there for him for that, and that was the last time I saw him. But we passed a few notes since.

Wasn’t that the ceremony where they also honored Leonard Cohen, and Cohen said, “All of us are footnotes to the words of Chuck Berry”?

Yeah, that was it.

Bob Dylan once said, “People don’t always realize how powerful the innovators are. Take someone like Chuck Berry. When his records came out, they were dangerous. There was nothing like them on the radio, they were like a stampede. Now all these bands just play it louder and faster and don’t really add anything to it. And so Chuck Berry, the creator, sounds ‘quaint’ and ‘old-fashioned.’… [Those records] are important pieces of art, and art isn’t looked at as something old or new, it’s looked at as something that moves ya.”

Would you agree?

This is true. I guess this is why you have to get beyond imitation. There is a certain part of me that still has my Chuck Berry niche, especially on the rhythm end, more than anything. I’ve learned more and more from him over the years of how to sling the hash. (He laughs.)

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

ALSO

Chuck Berry’s new ‘Chuck’ album set for June 16 posthumous release

Chuck Berry wasn’t just a god onstage — he was one onscreen too

‘It’s like “ratchet” dancing today’: Famed choreographer Frank Gatson Jr. on Chuck Berry’s moves

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.