Q&A: Former Times critic Robert Hilburn on writing about Paul Simon and the struggle to protect artistry

- Share via

Pop music writer Randy Lewis and pop music critic Robert Hilburn worked together at The Times for a quarter-century before Hilburn retired in 2006.

They sat down recently to talk about Hilburn’s latest book, “Paul Simon — The Life,” to be published by Simon & Schuster on Tuesday, just ahead of Simon’s farewell tour concerts at the Hollywood Bowl on May 22, 23 and 28.

This is Hilburn’s third book since leaving The Times, and follows “Johnny Cash — The Life” (Little, Brown & Company, 2013).

He is scheduled to do a book discussion and signing on May 17 at Book Soup in West Hollywood.

You chose Johnny Cash as the subject of your first biography. Why Paul Simon?

When I first went to the L.A. Times in 1970, the question I had was “Who should I write about?” When I began to interview people from the ’60s, my first question was always “What was your favorite record?” They would always say Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and maybe somebody else.

Then when I started interviewing people from the ’70s generation, and asked “What was your first record — who influenced you?” it was always the Beatles, the Stones, Bob Dylan, maybe somebody else — and Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry and Little Richard.

So I thought, maybe that’s what you do — you don’t try to follow who’s No. 1 every week, because that’s often somebody maybe nobody cares about. So I’m going to try to think of the artists who, 10 years from now, the musicians are going to say, and the fans are going to say, “That’s the person who was important.”

Still, a number of artists could fit that description.

While I was writing the Cash book, I saw Simon at the Henry Fonda Theatre across from the Pantages [in Hollywood]. He was doing the “So Beautiful or So What” tour [in 2011]. I listened to that album and I thought, “My God, that’s a great album.” I love the song “Questions for the Angels.” I was thinking, “Who else is active today who is writing music that can stand up to their earliest, best stuff?” Paul McCartney can’t, Brian Wilson can’t, Joni Mitchell can’t. Even Dylan — I’m not sure.

So after the Cash book, I tried to think “Who’s the best songwriter I can think of that would make an interesting book, and who would tell me about the whole issue of artistry: how artistry comes about and how you have to protect it?” There’s the issue of fame: Look at Elvis — he was destroyed by fame and womanizing and drugs and stuff. All these artists have these [hurdles]: marriage, divorce, changes in public taste, laziness, running out of talent.

That’s why I talked to people like Quincy Jones and Allen Toussaint, people who have worked with a lot of great talent, to see what characteristics they found [in Simon’s work]. And again, I thought Paul is so articulate, this would be fabulous. He could tell me about the songs.

You had Simon’s cooperation — something he’s never granted any other biographer — but you retained final approval. How did that sit with Simon?

There was this huge thing early on — in the second month, third month, fourth month. He said, “If you’re going to London, here are some people you ought to talk to,” and he had a whole list of names. He had people he had his secretary send notes to saying I’m going to be calling them. But then he said, “Now Kathy Chitty [his girlfriend during his early years living in England] is off limits.” And I thought, “Here we go.”

I waited maybe five minutes — this was in a series of emails. I thought, “What do I do? I can’t let this go any farther.” So I said, “Paul, I understand your concern and respect for Kathy and you don’t want to invade her life. But nobody can be off limits. If I’m talking to a reporter, and they say, “How come you didn’t talk to Kathy Chitty?” I’ve gotta be honest and say “Because she was off limits.” That can’t work, and it makes the whole book in question.

I told him, “You don’t have to help me find her. I’m not asking you to have your secretary contact her. But if I find her, and she wants to talk, you have to be OK with it.” Twenty seconds go by. Then he says, “I understand.” That really set the tone, and he never violated that.

He often comes across as a sober, even somber guy, yet there is a lot of subtle humor in his songs. How did his sense of humor come out during your time with him?

He and his son are big baseball fans and they have the All-Fish Team — all-time players with fish names [Mike Trout, Jim “Catfish” Hunter]. One day he said, “Of course, one of my favorite players on our team is Minnow Miñoso.” I’m thinking, “No, Paul, it’s not Minnow Miñoso, it’s Minnie Miñoso” [of the Negro League and the Chicago White Sox].

I was shaving the next morning, and I realized, “That was a joke!” It’s subtle like that — he doesn’t set it up. I sent a note back to him and said, “That was a joke, wasn’t it?” He sent the word “smile” back.

But he does have a reputation for being aloof.

He’s had this reputation of being prickly, kind of a stuck-up guy. Even in the book, he says that when Edie [Brickell, the singer-songwriter he married in 1992] meets him, she says “I heard you weren’t a very nice guy.” He says, “No, I never meant to be a bad guy, I try to be nice.” But he’s so focused.

That’s the thing people don’t understand: If Bob Dylan is sitting here, and you sat down with him and started talking, he wouldn’t sit there and say, “Hey, how ya doin’!” He’s got his own world. And Paul, if he’s thinking about a song, he’s not going to talk to you; Neil Young, he’s not going to talk to you. Now Bruce [Springsteen], he would try to talk to you. [Laughs again] Bono would try to talk to you.

But some of these guys are just so into their world. I remember I was doing an interview with Neil Young one time, driving around his big ranch up there [in Northern California], and he said, “I write a lot of songs in the car.” I said, “What if you start writing a song now?” He said, “The interview would be over.” That’s what they are. That’s their artistry. It’s the focus, the obsession they have.

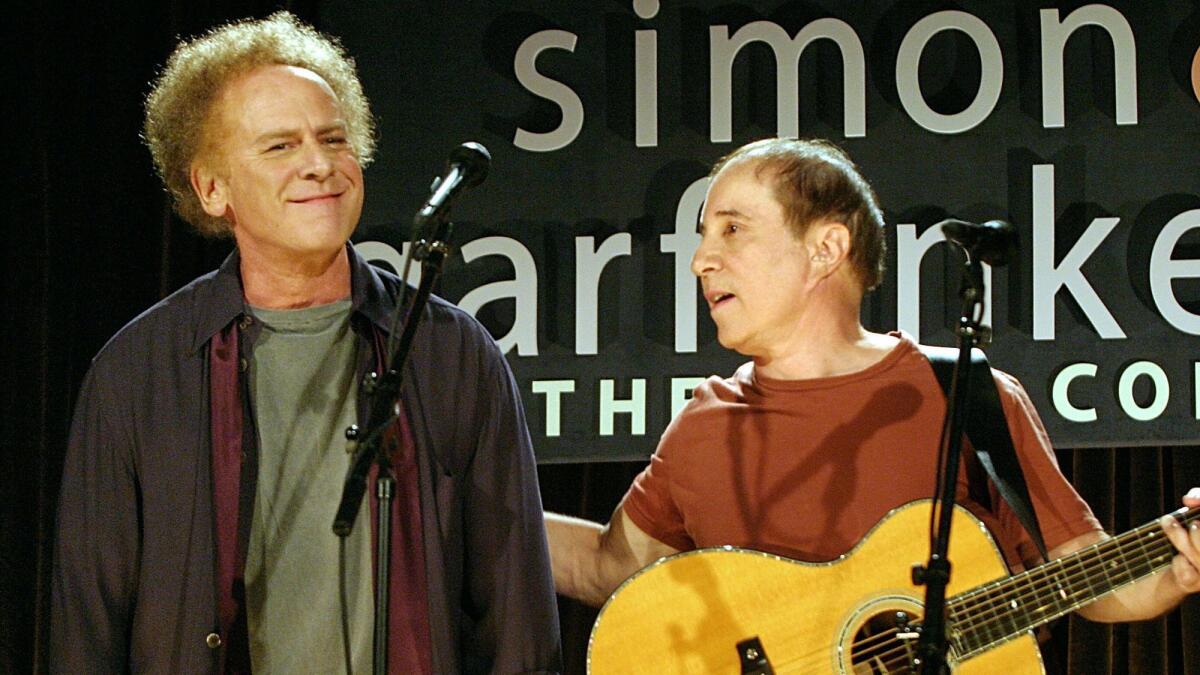

Speaking of artistry, you spend as much or more time in the book examining his music as you do raking over the details of his private life. You don’t gloss over his tempestuous relationship with Art Garfunkel, or his celebrity marriages to Carrie Fisher and more recently singer-songwriter Edie Brickell.

I think of it as two train tracks going in [parallel]: You’ve got to tell the personal story, because that’s what a biography is. But I think what’s important — beyond the personal story, which is essential — you’ve got to build on that and tell why he’s important. That’s the art part. And it went deeper into the art part than you almost ever see in a biography because, again, I wanted to stress the significance of it — why he’s remembered: those songs.

When you think of all these songs he wrote … it’s almost like I wanted it to be a case study in songwriting. But I didn’t want to do it to the exclusion of his private life.

So a casual fan will pick it up for the story. But for the person who wants to know about his significance and about the whole process of songwriting, that’s the second train. I’m fascinated by both of them — but the second train is what gives the book its significance.

Paul Simon has been the subject of controversy over the years — especially his run-in with the African National Congress over charges that he violated a cultural boycott of South Africa when he collaborated with musicians there for his “Graceland” album while apartheid was still in effect.

“Graceland” is the significant thing, and his philosophy is he doesn’t think anybody’s got the right to tell [an artist] what you can do. His view was, “The ANC is a political party. I don’t want the Democratic Party or the Republican Party [here] telling me what I can do. I don’t want to ask their permission.” That was in essence what he said. He was defending artistry — he even wrote a column in the New York Times about that.

I don’t try to make his case, but he would say, “That’s what artists do: You fight battles; you’re going to find record company presidents who don’t like what you do and try to change you. You’re going to find all kinds of [obstacles] and you’ve got to fight through that.” Whether it’s writing a song and not giving up, in his mind he was justified. He talked to Quincy Jones, he talked to Harry Belafonte. He wasn’t unaware of the potential for problems. But the musicians wanted to work with him, and that was fine. So I think he’s pleased with that chapter [of his life]. He thinks he did the right thing, and I think he did the right thing.

One of my favorite sections is the one where he talks about writing “Darling Lorraine,” which he considers one of his best songs. It’s fascinating when the man who wrote it says he was surprised when the song about two people long into their relationship takes an unexpectedly dark plot turn.

That’s the big thing I learned: He writes in an unusual way. He doesn’t pick a theme and write about it; he plays the guitar until something resonates in him. Then he tries to figure out what that feeling is and write about that, taking one line at a time, until he discovers what he’s writing about. That’s the discovery.

He said when he was writing [the song] “Graceland” — that line [emerged] that just took the breath out of me: “She said losing love is like a window in your heart / Everybody sees you’re blown apart.” Those things come out. It’s partially subconscious.

That’s why he left Simon & Garfunkel. He was probably burned out by the ’70s. He knew he had done all he could with those three [fundamental rock-pop] chords, so he set out to educate himself about other kinds of music so he could make more music: gospel music, Latin music, Cajun music, South African music — something else that would inspire him.

Did you reach a conclusion about how he has continued to make music that compares favorably to his early output?

Fame never became more important, money never became more important, nothing became more important than his music. And for much of his life he suffered because of that; his relationships suffered. Gradually after “Graceland,” he starts opening up his life, and with his marriage to Edie, now he’s found a balance.

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.