In a time of political and social upheaval, artists at SXSW turned to self-preservation

- Share via

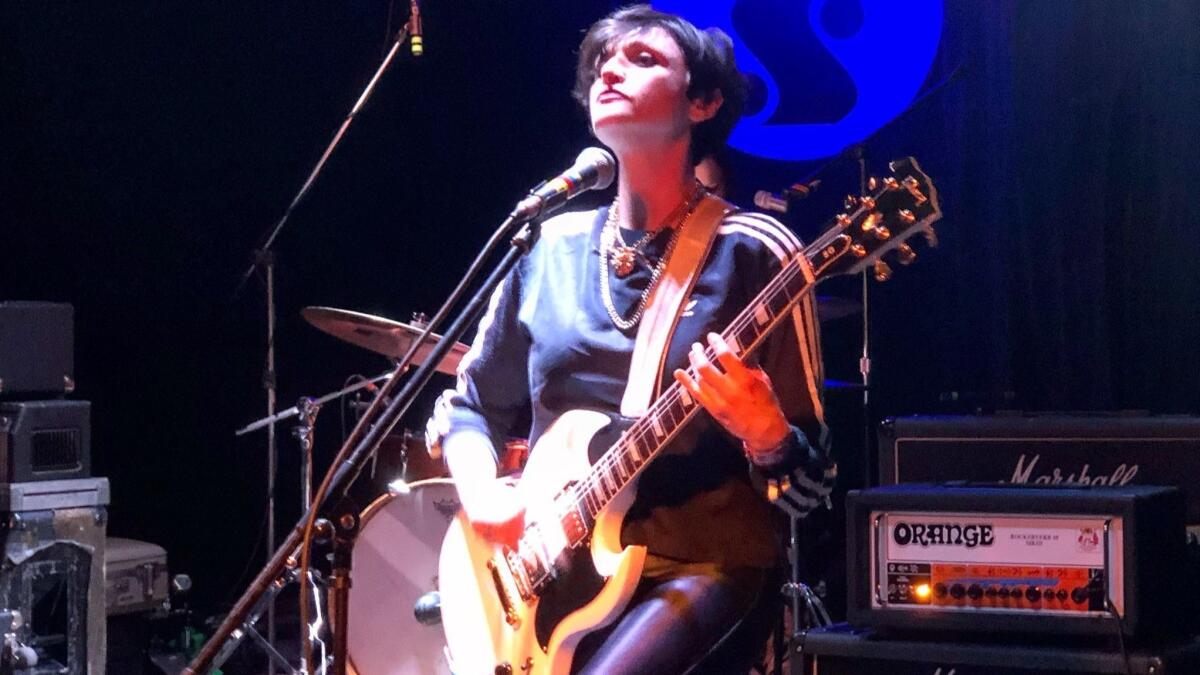

Reporting from Austin, Texas — Mid-20s Australian artist Stella Donnelly was about halfway through “Mean to Me,” a song about a no-good significant other who criticizes her jokes, acts bored in her presence and lacks even a sliver of human decency, when she decided to lighten the mood with the lilt of a violin.

It was a clever sleight-of-hand, given that the only instrument in sight was her electric guitar. So she improvised. She began swaying the guitar, bowing before the microphone and mimicking the wordless accompaniment, as if she was suddenly an unvanquished star in her own orchestra. Mission accomplished: where bitterness had once filled the room, now there was laughter.

Donnelly was one of a number of artists who descended upon Austin, Texas, for the annual South by Southwest festival and conference whose art was openly frank about real life and remarkably cognizant of the audience, so much so that her songs extended a hand as much as they told a story or presented a point of view.

The 10-day event, in which more than 70,000 registered attendees explored various entertainment disciplines — film, television, music and interactive entertainment — has always had a rebellious spirit, be it celebrating underground music or disruptive technologies. But as SXSW’s film festival handed the baton to the music and gaming industries this past week, a distinct sense of revolution hung in the air.

Though political and socially aware, with many an artist touching on the various anxieties of life in 2018, music such as Donnelly’s was neither the clenched-fist tone of ’70s punk rock nor the nihilistic, preaching-to-the-choir feel of ’90s alt-rock. And it definitely wasn’t about escapism — an observation that could also be made regarding some of the seemingly out-there games and interactive installations showcased.

While frustration and anger could be found underlying much of the best work of this year’s SXSW, more prevalent was self-preservation. What stood out was less a need to confront and more a desire for connecting — the real-life, face-to-face kind — where rage, humor and even empathy were equal parts of an artist’s toolbox.

Rising British country singer Jade Bird described nearly every other song of hers as “sassy,” a warning, perhaps, that she was about to get real, but she also sought to assure the audience that they could still drink and party to them. She put a more domesticated spin on the #MeToo and Time’s Up era, as her outlaw spirit, fiery riffs and ready-to-roar vocals illustrated everyday gender dynamics (“I’m your girlfriend, not your maid,” she shouted in one song).

The indiscretions she described were of the eye-rolling sort — “She asks if you love her and you nod and say, ‘uh-huh,’” she sang in another tune — but the force in which she struck her acoustic guitar made it clear these errors in judgment would not stand.

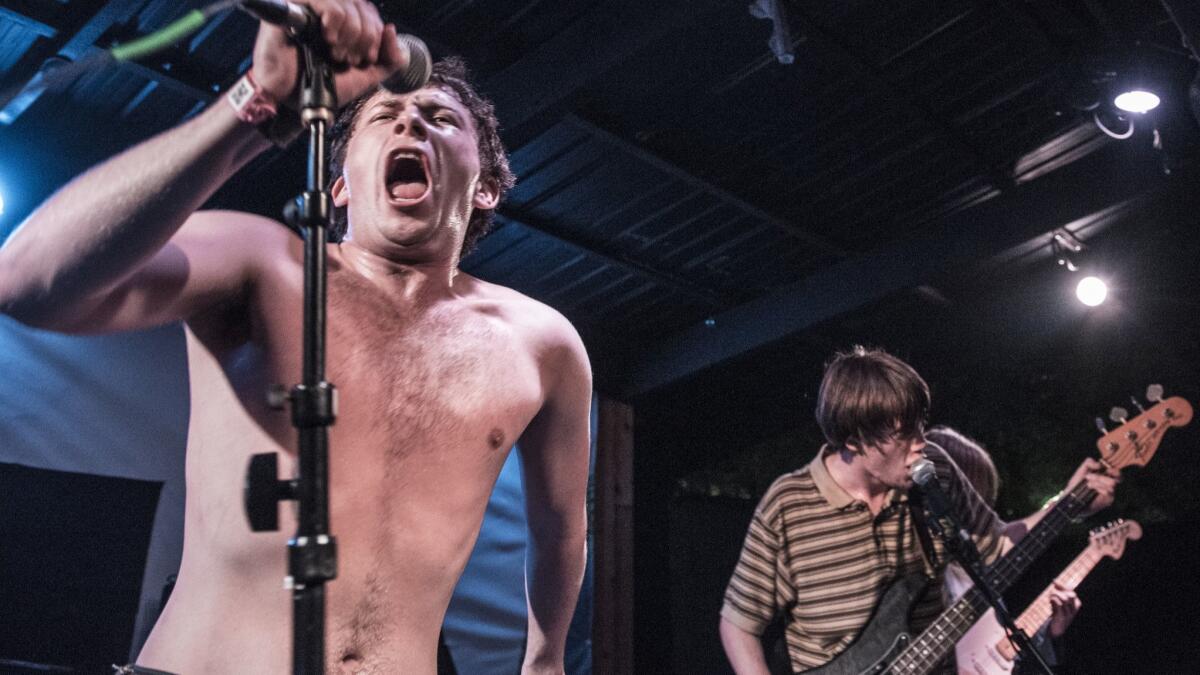

Perhaps the most buzzed-about band in Austin was British rockers Shame, whose all-fury, all-the-time songs are tightly wound, punk-rock clamor. It’s music that sounds like it’s looking for a fight, but Shame’s bite appears harder than it is, as evidenced by the act’s between song silliness and jokes about succumbing to rock-star clichés such as going shirtless .

But with so much to stress about, perhaps such humor is a necessity. “In a time of such injustice, how can you not want to be heard?” sings Charlie Steen on “Friction,” his aggression not at all about shouting into the void but of seeking to organize.

Donnelly’s best-known number, “Boys Will be Boys,” is as fragile as a lullaby as it details not only the rape of a friend, but the culture that allowed the perpetrator to go unpunished. At least for now: “I will never let you rest,” she calmly sings in the song’s deciding moment. It’s intense, but takes a personal account and broadens it into a resonant call for widespread change.

And yet understanding that today’s audiences are under siege from breaking news alerts and social media notifications alluding to another social or political crisis, Donnelly, who performs March 26 at downtown’s Moroccan Lounge, immediately sought to assure the audience that not everything would be so weighty.

“This next song is about Christmas in Australia,” she shouted. Only it wasn’t. The cut chronicled how to dance around a racist and homophobic relative during the holidays. Yet even here, the goal wasn’t to simply highlight a problem but to turn a potential hairy situation into one of familial bonding.

If there was an overriding theme at the festival, it may have been best articulated by veteran rocker Ted Leo. Long associated with the punk-rock scene, Leo has flirted with pop and his latest, “The Hanged Man,” elegantly deals with the difficult subjects inspired by a personal health scare.

Survival in music, said Leo at one afternoon panel in the Austin Convention Center, requires a “perpetual curiosity to actually learn about what’s happening, a curiosity that almost makes it fun to figure out the approaching challenges.”

And make no mistake, there was plenty of fun to be had in Austin.

North Carolina’s Bat Fangs even had a theme song — “Fangs Out,” which, said leader and guitar ace Betsy Wright, is “silly, just go with it.” In the course of about 30 minutes, Wright and her two bandmates cycled through a bevy of hard-rock guitar tones, touching on trippy excursions one moment, rockabilly journeys the next and plenty of metal in between.

Bat Fangs closed its SXSW sets with a cover of Poison’s “Talk Dirty to Me,” giving the ’80s hair-metal song a glammed-up, punkier edge, but even that treatment couldn’t disguise how dumb of a tune it is to begin with. And yet the song still felt vital in the hands of Bat Fangs, who reclaimed this relic from one of rock ’n’ roll’s most overtly sexist eras.

Those who took the time to explore what SXSW had to offer outside the clubs would find that similar themes were prevalent in other disciplines. It was perhaps no surprise that the most exciting talk to come out of SXSW’s gaming initiatives was a discussion from L.A.’s Thatgamecompany, who are busy putting the finishing touches on “Sky,” which is slated to be released this year for Apple platforms.

The follow-up to “Journey,” an abstract game about communication, “Sky” owns similar themes. Little is known about the title at this point, but Thatgamecompany continues to explore how strangers can connect and, essentially, learn a new language given only a few tools. Their games emphasize cooperation and politeness, ultimately seeking to show that our differences are not unsolvable if we just, well, listen to one another.

It was telling, then, that late one night Julia Steiner of the band Ratboys — a buoyant rock act from Chicago that can turn a song about losing a cat into a hearty Midwestern anthem — realized she made the mistake of bringing her smartphone on stage. She picked it up and tossed it aside, expressing annoyance at the pointless yet distracting notifications she was receiving from Twitter (“Judd Apatow liked a tweet,” she mocked).

Far more healthy were the connections she was making with the audience that night, and there was no song as “SXSW” as Donnelly’s “I Should Have Stayed at Home,” a moment of pop convergence that bridges music and interactive disciplines and chronicles a not-so-hot Tinder date (“I should have swiped left,” she sings.)

It was, like much of SXSW, a tacit acknowledgment that while there can be plenty of advantages to online connections, ultimately there’s more power in actual conversations.

Follow me on Twitter: @toddmartens

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.