Appreciation: Pianist Dave Brubeck’s gift for timing endures

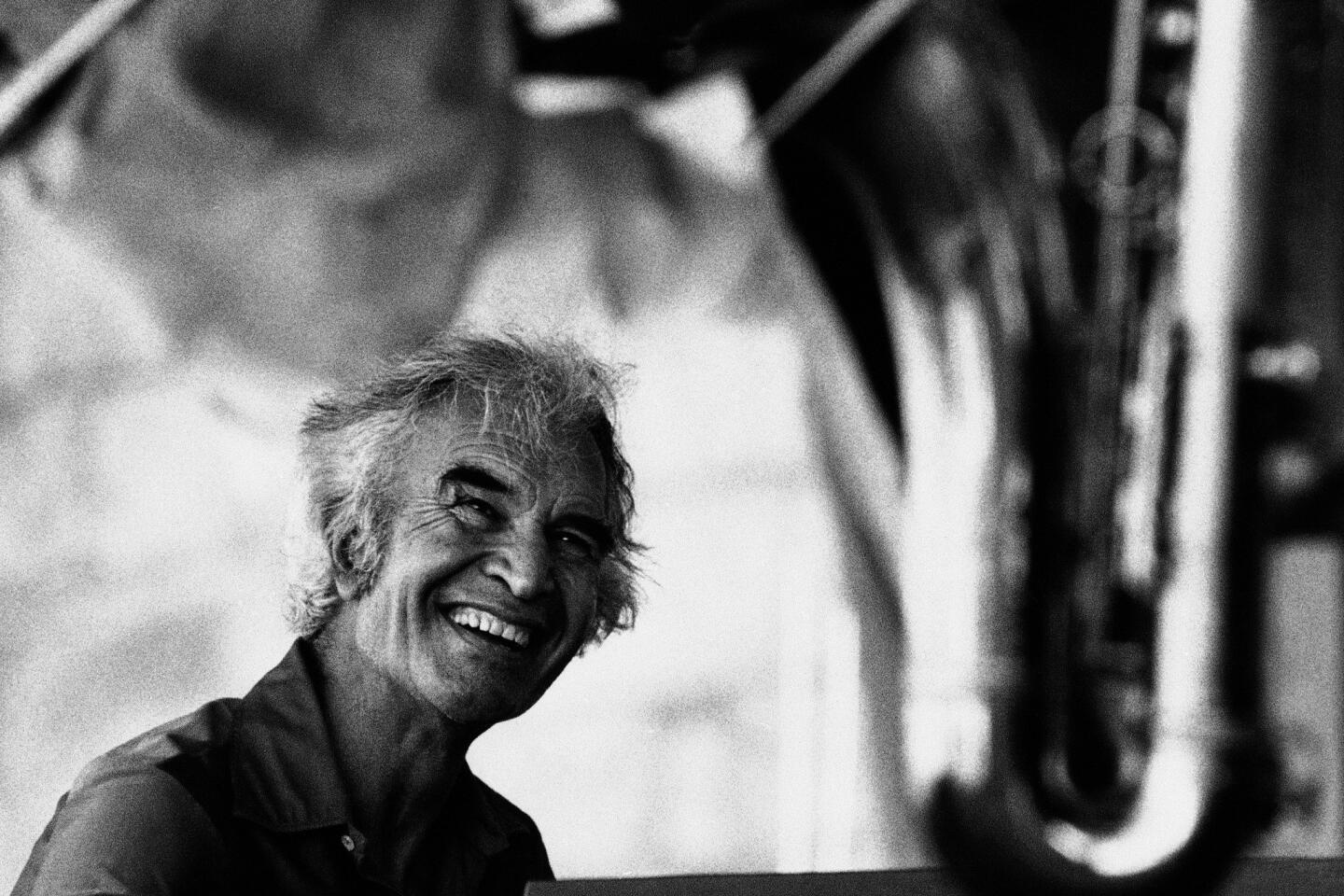

When thinking about Dave Brubeck, you can’t help but also consider time, and not just how much of it fans received from the prolific jazz pianist up to his death Wednesday at age 91.

A titan of West Coast jazz, Brubeck was linked with California for much of his career. He was born in Concord, studied at what is now is the University of the Pacific in Stockton and recorded for Berkeley-based Fantasy Records, which helped forge the Bay Area’s sound in the ‘50s. But regardless of where a listener was based, the Dave Brubeck catalog was an inevitable destination.

Part of the reason is “Time Out,” the aptly named 1959 recording that stands with Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue,” Charles Mingus’ “Mingus Ah Um” and Ornette Coleman’s “Shape of Jazz to Come” as a groundbreaking album during a pivotal year in the evolution of jazz. Where Davis explored modal structures and Coleman blazed into a new world of saxophone, Brubeck was equally inventive for his experimentation with jazz’s heartbeat.

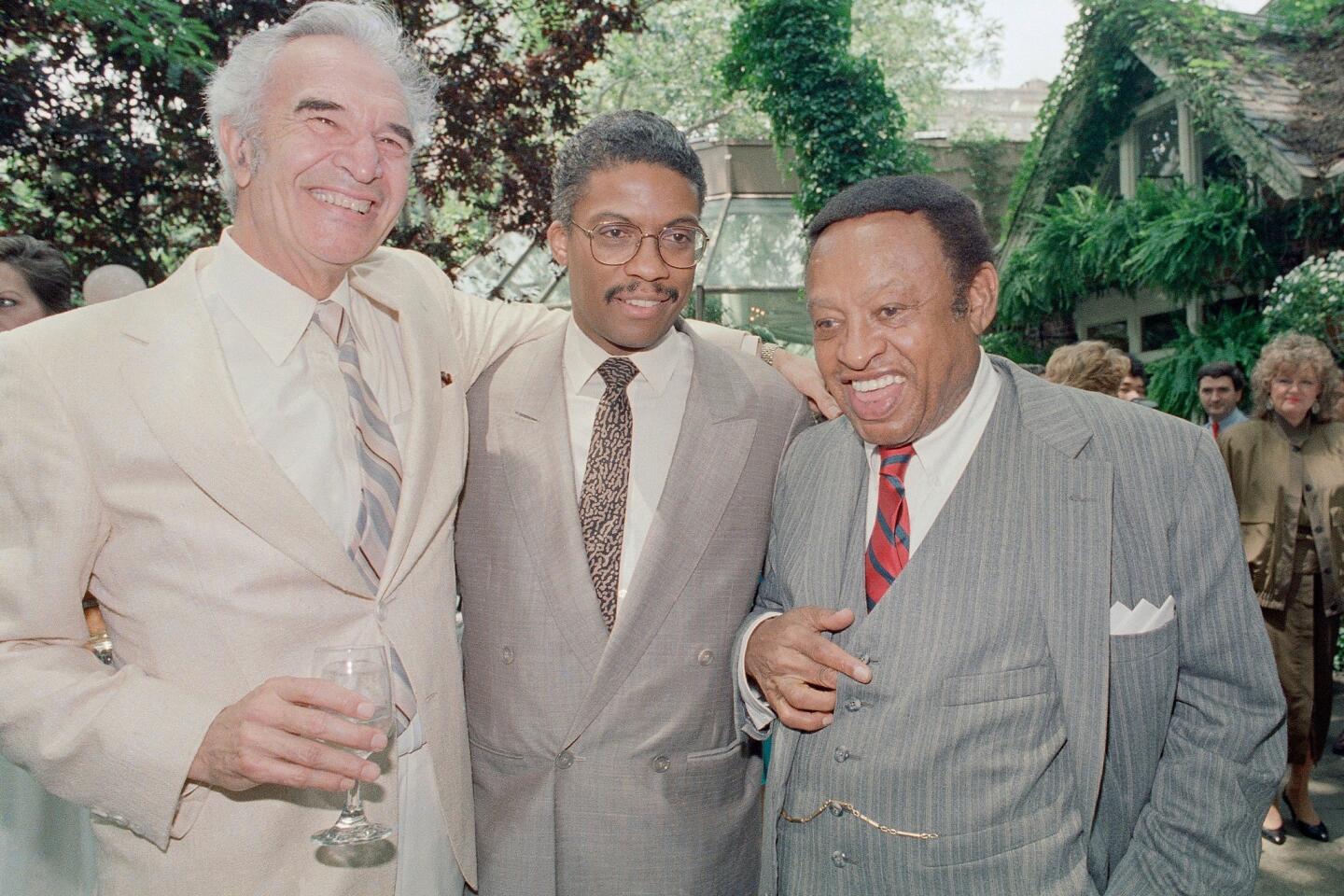

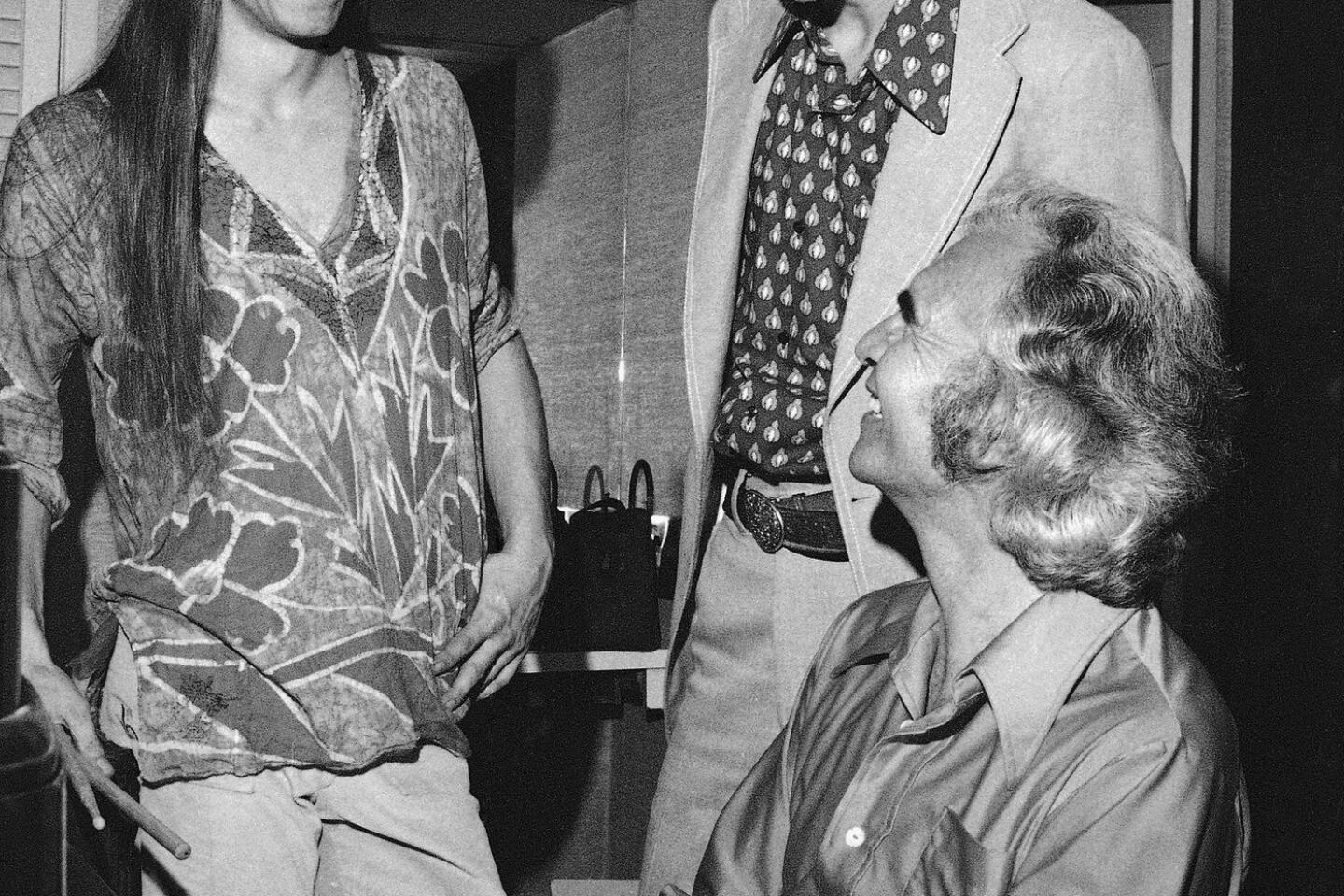

PHOTOS: Dave Brubeck | 1920 - 2012 | Obituary

Written by Brubeck’s saxophonist Paul Desmond, the immediately recognizable “Take Five” was in 5/4; “Blue Rondo à la Turk” -- a song inspired by Turkish folk music Brubeck heard while on State Department-sponsored tour -- shifts between 9/8 and 4/4; and the whole album continues the theme, shifting between waltz, double waltz and straight time with impossible ease.

To casual music listeners, such information can look like a fractions exam, but these songs upended the idea of what a jazz song could do. Despite fundamental structure changes (most jazz ticks along at 4/4), Brubeck still swung, and beautifully so.

Even at Brubeck’s most inventive, he remained approachable. “Blue Rondo à la Turk” might have drawn a line in the sand as an album opener with its stuttering, almost manically paced beginning, but the song hardly sounds jagged as it gives way to a more familiar, blues-oriented section. The approach was new but never unwelcoming.

The proof is in the album’s reception. Although Brubeck’s label Columbia feared he might have gone too far out, the record became one of the bestselling jazz recordings of all time, peaking at No. 2 on the Billboard pop charts, and “Take Five” became a Top 40 single.

ARCHIVES: Dave Brubeck says he’s ‘fortunate’ at 90

The song’s appeal endures, having even appeared in an otherwise blandly elegant TV commercial for a Japanese luxury sedan in the ‘90s. The ad might not have sold a lot of cars, but it inspired many to go record shopping (this writer included).

Of course, with a life that found Brubeck performing high-profile gigs well into this century, it’s difficult to summarize his impact and appeal in the context of one album. His reputation was established years before as he became only the second jazz artist to be featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1954 (though Brubeck questioned the honor and was reported to have said he thought Duke Ellington was more deserving). Brubeck continued to further explore exotic meters with his “Time Out” quartet until 1967.

A live recording from one of the band’s last dates, “Their Last Time Out,” was released in 2011 and still shows the pianist full of invention before shifting focus to composing more orchestral pieces. But Brubeck remains most memorable for his timing, and over such a long, fertile career it always seemed right.

ALSO:

Jazz pianist Austin Peralta dead at 22

Review: Robert Glasper Experiment at Royce Hall

Critic’s Notebook: Vince Guaraldi’s ‘A Charlie Brown Christmas’ score is a gift

Twitter: @chrisbarton

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.