LACMA traces photography’s New Topographics movement

No one disputes that the 1975 exhibition “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape” was a landmark show. Attendance at the George Eastman House in Rochester, N.Y., wasn’t huge, and the presentation didn’t introduce any unknown talent.

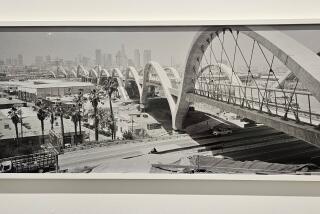

But the show put a name to a phenomenon -- the proliferation of straight, seemingly uninflected photography of the banal, built environment -- and that name stuck. What remains cause for discussion is what exactly New Topographics meant and why the term and its attendant attributes have had such an enduring influence. A restaging of the exhibition at the L.A. County Museum of Art provides a framework for the debate. More than 100 of the 168 photographs in the original show have been reassembled, about 10 each by Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore and Henry Wessel Jr. The new version of the show is a collaboration between the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film and the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona.

William Jenkins, assistant curator at the Eastman House in the ‘70s, conceived and organized the original show in consultation with Deal, who worked there as exhibitions manager. Many of the artists they included had crossed paths as graduate students, been in shows together or were friends, but in no way did they constitute a unified “school.”

“I think all of us had reservations about the premise of the show,” recalled Gohlke at the LACMA opening. “Everybody, I think, told Bill, ‘It’s a good idea, but it doesn’t fit me,’ ” he said, laughing. “Everybody had their own objections, but Bill and Joe identified something that was happening and that this work seemed to bring into focus. Something in the air got crystallized.”

Gohlke was represented in the show by crisp, plain-spoken images of the zigzagging stripes of a Kmart parking lot, a pair of bulb-crowned sawdust incinerators, the distilled sweep of a concrete-walled irrigation canal. Baltz showed pictures from his recently published series on industrial parks in Orange County -- stark images of expedient structures embellished with sparse, gratuitous landscaping. Selections from Adams’ 1974 series “The New West” depicted a spreading rash of tract housing in suburban Colorado. Schott’s work chronicled the idiosyncratic array of motels along Route 66.

What was in the air that settled into these modest-sized, well-printed images of defiantly ordinary and sometimes overtly unattractive sites? Essays in the exhibition catalog -- a major production compared to the slim publication accompanying the show in ’75 -- describe the myriad social and artistic forces that converged to generate New Topographics photography: a growing awareness of the exploitation of the American landscape, the rise of the environmental movement, the emergence of cultural landscape studies as an academic discipline, new appreciation of the commercial vernacular, epitomized by the 1972 publication of “Learning From Las Vegas” by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown.

Ed Ruscha (whom Jenkins said he wished he’d included in the show) produced a series of photographic books in the early ‘60s -- “Twentysix Gasoline Stations,” “Some Los Angeles Apartments” and others -- whose stripped-down, deadpan aesthetic laid a foundation for the later work.

Walker Evans, the subject of a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971, was also a seminal influence. His record of American vernacular architecture, shot in what he defined as the “ documentary style” with seeming neutrality, proved a model. Focusing on the real and everyday, the photographers turned away from the idealized landscape imagery of the past. They expanded the landscape genre to include not only nature but also culture, not just the sublime but also the mundane.

“I was very conscious that my progenitors -- Ansel Adams, Paul Caponigro, Edward Weston -- were all photographers for whom the landscape was a heroic enterprise,” said Schott, standing amid the opening-night crowd. They would position their cameras “to find a landscape that was absent of human intervention, a place of pristine beauty. This work basically said there’s a new world to be seen, and it deserves to be looked at, whether you see it as despoiling the landscape or simply as a fact.”

Through broad publication and exhibition of their work, these photographers gave a new legitimacy to imagery of the banal. Not surprisingly, the pictures weren’t universally well received.

“What I remember most clearly from the original show,” Gohlke recalled, “was that almost nobody liked it. I think it wouldn’t be too strong to say that it was a vigorously hated show. Some people found it unutterably boring. Some people couldn’t believe we were serious, taking pictures of this stuff. And actually, that attitude is still very alive and well.”

During the ‘70s, artists were also expanding upon the menu of photographic options with alternative printing methods, manipulations of the negative and printing on unorthodox surfaces. All of the photographers in the “New Topographics” show shot and printed in conventional black and white, except for Shore, who worked in color. “For a lot of people,” Gohlke continued, “this work seemed really retrograde. What -- you’re still using large-format cameras and making black-and-white prints?”

Photos that transform

Mark Ruwedel, a Long Beach-based photographer, led a walkthrough of the LACMA show recently, the first of six L.A. artists scheduled to share their perspectives on the quietly radical work. When you first see this material, he said, it can actually be shocking.

“The pictures are so reticent. By today’s standards, they’re small and mean. They’re pictures of things that most people don’t find interesting. They seem to be without personal inflection. I know that’s an illusion, but it’s a really interesting one.”

Ruwedel’s work shares some traits and influences (19th century survey photography as well as Evans) with New Topographics photography. In one recently published long-term project, “Westward the Course of Empire,” Ruwedel captured with sober clarity the abandoned railroad lines of the Western U.S. and Canada. He was first introduced to the idea of topographics when others started using the term to describe his graduate school work in the early ‘80s. A sense of permission came from learning more about the photographers to whom he was being compared.

“The example of those photographers suggested something about landscape being a viable place to work. In fact it was a place where one could make social inquiry and think about contemporary art issues.”

The New Topographics work began to bridge the divide between the ghettoized world of photography and the wider contemporary art scene. Many of the work’s characteristics -- “the descriptive mode, the refusal of lofty expression, a certain flirtation with irony, a fascination with the vernacular,” according to Schott -- permeate the work of contemporary photographers such as Andreas Gursky and Candida Hofer, for whom crossover into the general art world is now a given.

It was, in part, because so many artists working today cite the influence of New Topographics photography on their work that Britt Salvesen, formerly of the Center for Creative Photography and newly at LACMA, felt motivated to reprise the 1975 show. She started doing research for the project in 2006, collaborating with Alison Nordstrom of the Eastman House, where the new show, like the old, debuted. The LACMA opening came just five days into her tenure as department head and curator, Prints and Drawings Department and the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department.

“The exhibition isn’t presented as a time capsule or in the spirit of nostalgia,” Salvesen said. It exemplifies a vision for the museum’s photography department, “one that links the history of photography with its contemporary articulations.”

She has encouraged all the venues on the eight-city, international tour to complement the show with offerings that help bring an understanding of New Topographics into the present. The walkthroughs by contemporary photographers at LACMA are one such amendment. Another is an installation the museum commissioned from the Culver City-based Center for Land Use Interpretation. The center’s projection of paired “landscans,” looped video footage of the pumpjack fields of Kern County and oil refineries in Texas, serves as a bookend to the show.

Many feel the topic is far from exhausted. Said Gohlke, “Work that’s inspired by this idea, even if it’s not a great picture, at least has the advantage that it’s a picture of the world. . . . Just the world itself, carefully observed, transformed in the way that pictures transform things -- is not only sufficient, it’s more than you can comprehend in a lifetime.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.