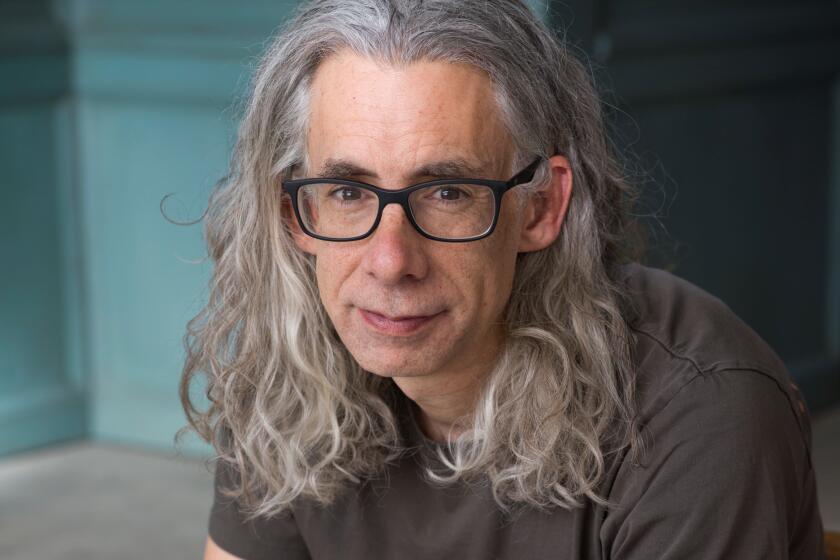

‘Hugo’ author Brian Selznick in a ‘Wonderstruck’ mind-set

So here’s Brian Selznick, on a Friday afternoon in Culver City, standing in the vestibule of the Museum of Jurassic Technology, a grin of anticipation on his face. It was, after all, this storefront museum — “the museum as performance art,” Selznick calls it — that inspired “Wonderstruck,” his most recent novel for middle readers, which takes place, in part, at New York’s Museum of Natural History and plays with the idea of the museum as what was once known as a wonder cabinet: a collection meant “to fill you, literally, with wonder, in the old-fashioned sense of amazement and awe.”

That’s the ethos of the Museum of Jurassic Technology, which walks a line between fact and fiction, displaying both invented and authentic artifacts, challenging our sense of believability, asking how far we are willing to go.

“What’s thrilling,” Selznick says, as he begins to walk through the museum, stopping at exhibit after exhibit, “is that what’s true and what isn’t true, it’s all the same. They’re all fascinating stories, and they all move you in some way. It makes you think about that term, cabinet of wonders, and what wonder means. If a museum’s job is to inspire you, this place does that job.”

There’s a metaphor in this, for Selznick is very much in the business of wonder himself, creating books that challenge our notions of how fiction (for young readers or otherwise) is supposed to work. His 2007 novel “The Invention of Hugo Cabret,” which won a Caldecott Medal and was a National Book Award finalist, introduced an innovative strategy for blending words and images, interweaving narrative and picture sequences to tell two sides of a single story, in which an orphan, living in a Paris train station at the dawn of the 1930s, forges an unlikely friendship with the pioneering French filmmaker Georges Méliès.

The book has just been turned into the movie “Hugo,” Martin Scorsese’s first foray into 3-D and his first work for kids. Yet even before Scorsese got involved, Selznick knew he wanted to experiment with the conventions of visual storytelling, to use “full double page spreads with one image covering the whole spread, and then, on the next page, to move the story forward by zooming in on something, or panning or editing, which echoes what happens in cinema.”

For Selznick, this was a necessary challenge, since the book “has a lot to do with the early history of cinema,” and comes coded “with all these old French movies, both in actual film stills and within my drawings, where I’ve hidden references to certain films.”

He laughs, his square face animated behind a wisp of beard. “Of course,” he goes on, “Scorsese got all that, and then he made a movie filled with references to the history of cinema, which is amazing because that’s so much of what the story is about.” Indeed, among the pleasures of the movie are its painstaking re-creations of Méliès’ work, which was, as Selznick’s novel tells us, once written off as lost.

“Wonderstruck” operates in much the same way as “The Invention of Hugo Cabret,” juxtaposing prose and visual material, tracing the relationship between an orphaned boy and an older mentor, with whom he discovers an unknown bond. Unlike its predecessor, it involves two story lines that ultimately come together after existing, for much of the novel, in two distinct time periods: the 1920s and the 1970s.

“When it was time to do my next book,” Selznick explains, “I wanted to take what I’d learned and do something new. First, I got the idea to tell two separate stories, one with words and one with pictures, and then I started collecting ideas.”

The idea that stuck had to do with deafness, which became a major theme. Neither of the central characters — Ben, a Minnesota adolescent living with his aunt and uncle after the death of his mother, and Rose, who gazes at Manhattan from her home in 1920s Hoboken, longing for the city just beyond her reach — are able to hear, which presents certain narrative challenges, especially in the graphic sections of the book.

“I had seen a documentary called ‘Through Deaf Eyes,’” Selznick recalls, “about the history of deaf culture, deaf education, and there was a quote: ‘The deaf are the people of the eye.’ So I thought it might be interesting to tell the story of a deaf person just with pictures. That way, how we experience their story echoes the way they experience their life. But it was difficult to figure out how to do that just with pictures, so, there are a lot of places where I open up the images to words. I have newspaper clippings, I have books, I have postcards, I have lots of things that are written within the drawn world.”

This is the trick with “Wonderstruck” and “The Invention of Hugo Cabret,” the issue of how far to push the boundaries, how much to include and how much to strip away. Still, at the heart of both books is an assurance about what visual storytelling can do.

“When I first presented ‘Hugo’ to Scholastic,” Selznick says of his publishing house, “it was going to have one drawing per chapter and be about 100 pages. But the more I thought about the book, the more I thought it might be interesting to try to tell the story like a movie. That’s when I took out some of the text and replaced it with picture sequences.”

By the time he was done replacing text with image, the book had grown to 534 pages; “Wonderstruck” is even longer, although it was constructed in a similar way. “I may think in pictures,” Selznick acknowledges, “but first I write everything out in words. So with ‘Wonderstruck,’ I started by writing present tense narratives: There is a boy, he lives in Minnesota; there is a girl, she lives in Hoboken, N.J. I knew I was going to tell the story in pictures but I was just getting down the essence of the plot.”

With “Wonderstruck” out and “Hugo” in theaters, Selznick has begun a new book that relies on the interplay of image and word. “I think I have one more in me,” he laughs, “although after this, I’m a little adrift.” But then, he would tell you, that’s the nature of the enterprise.

“I didn’t know how ‘Hugo’ would turn out,” he reflects, voice quiet with remembering. “I didn’t know if anyone would read it — it’s a children’s book about French silent movies — but it was the thing I wanted to make. I made ‘Wonderstruck’ in the same state of mind. I’ve always liked stories that connect to something larger, where things are heightened in a certain sense. It’s not magic, exactly; I’m not interested in writing stories that have magic in them, but in stories that feel magical, where there are synchronicities and unusual events. They remind us wonderful things do happen, that the world is bigger than we know.”

He looks around, gestures at the exhibits on the walls. “That’s what a museum does also, encouraging us to see things in a different way.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.