Harvey Pekar: An Appreciation

Here’s a phrase you don’t often hear in regard to Harvey Pekar: role model. And yet, it seems an apt description of the iconoclastic comics genius, who was found dead early Monday at age 70 in his Cleveland Heights, Ohio, home. Think about it — a longtime VA hospital file clerk with no ability to draw, Pekar essentially reinvented himself, in his 30s, as the creator of “American Splendor,” perhaps the greatest of all the underground comics. It is difficult to imagine the subsequent history of the form without its influence.

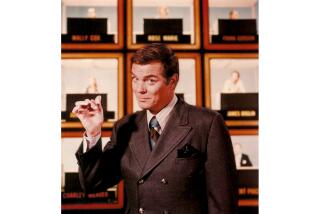

Even more, he yielded nothing, angering those who might help him for what at times seemed like capricious reflex. In the late 1980s, he was banned from “Late Night With David Letterman” after a series of contentious appearances, including one during which he wore a T-shirt that declared “On Strike Against NBC” while launching into an extended rant about its corporate parent, GE. Invited back to make amends, he accused Letterman of being a corporate shill. It was discomforting, funny in a provocative way. And yet, to watch those clips now on YouTube is to see something authentic and subversive, the talk show as Dadaist political experiment, in which the power of the open mike is used, even for a few minutes, to pry back the slick veneer of entertainment culture and expose the contradictions underneath.

That is what Pekar did, in his work and in his life. For Pekar, the two were inseparable, feeding into each other in a fluid back-and-forth. The animating concept was, as he wrote in his introduction to “The Best American Comics 2006,” “[T]here was no limit to what you could do with [comics]. They could be like novels or films. The only thing limiting the growth of comics was the people who produced them, from the artists and writers to the publishers, who couldn’t see comics as anything but a medium for kids.”

One early effort, “The Harvey Pekar Name Story,” uses 48 panels to pose a quintessential meditation, in which Pekar offers an extended riff on his name. This is a comic in which, literally, nothing happens, in which even the images barely change from frame to frame. Still, by seizing the potential of the genre to incorporate even the most interior investigations, Pekar effectively upped the ante, pushing us to reconsider what kinds of stories might be encompassed by the form.

Among the keys to “The Harvey Pekar Name Story” is R. Crumb, who illustrated the comic, as he did much of Pekar’s early work. It was Crumb, in fact, who stirred Pekar’s interest in comics; the two became friends after Crumb moved to Cleveland in 1962. Twenty-four years later, when Doubleday published an anthology culled from the first nine issues of “American Splendor,” Crumb described Pekar’s process in an introduction: “Usually he writes his story ideas soon after the event while the nuances of it are still fresh in his mind. He always has a large backlog of these stories, which he can choose from to compose each new issue of ‘American Splendor.’ He writes the stories in a crudely laid-out comic page format using stick figures, with the dialogue over their heads, and some descriptive directions for the artist to work from. The next phase involves calling up various artists and haranguing them to take on particular stories.”

Although Crumb went on to note that “Harvey is often frustrated by the artists’ lack of ability to break out of the standard heroic comic book style of portraying characters,” Pekar’s collaborations were striking and diverse. It was not uncommon in a single issue of “American Splendor” to find a dozen stories drawn by an array of illustrators (Gary Dumm, Frank Stack, Dean Haspiel), so that to read them all was like looking at Pekar’s life through a prism, in which the different styles, the different angles, refract back on themselves. This, too, was part of his genius, reflecting his belief that there was no central throughline, no larger narrative, that we had to make our lives, our art, our meaning out of moments, to find, as Crumb put it, the “drama in the most ordinary and routine of days.” Even Pekar’s long-form efforts — in 1994, he and his wife Joyce Brabner collaborated with Stack on “Our Cancer Year,” about his battle with lymphoma, and, in 2005, he and Haspiel produced “The Quitter,” a look back at the difficulties of his early life — highlight the most defining experiences in oddly offhand terms. “Oh well,” he writes in “The Quitter.” “…In the long run, we’re all dead anyway.”

Pekar, by all accounts, was a tough guy to be around: angry, confrontational, beset by grudges and troubles over money, an obsessive worrier. He never hid any of this, but wrote about it instead. That made him as brave as almost any artist I can think of — unadorned, unfiltered, less concerned with how the world thought of him than with how he thought of himself. It also made him an essential aesthetic bridge between, say, Will Eisner, who mined the lives of ordinary people in his 1978 graphic novel “A Contract with God,” and contemporary artists such as Jessica Abel, Adrian Tomine and Alison Bechdel, whose comics traverse a similar existential territory, in which the mundane (and sometimes not-so-mundane) material of daily life becomes the substance of their work.

We may live in a world of mendacity, but Pekar told the truth. In the 1984 piece “Hypothetical Quandary,” he details, in three understated pages, a Sunday morning trip to the bakery. The narrative is almost nonexistent: a quick car ride, a few thought balloons, an internal monologue about a publisher who never got back to him. Then, in the final panels, an epiphany — his obsessions are stilled, briefly, by the smell of fresh bread. It’s a fleeting moment, but, of course, so is life.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.