Behind that ‘Pirate’ spirit

“Pirate Radio,” the movie, isn’t really about pirate radio. It may take place on a boat in England’s North Sea in the late ‘60s, but anyone who goes to see the film hoping to learn about the realities of illegally broadcasting music to millions of idolizing fans from the cold and rocking waters of a ship are likely to be disappointed by everything but the soundtrack. “Pirate Radio” is a comedic coming-of-age story. The station in which that happens is merely a backdrop.

Pirate radio, as a concept, has long been a subject of interest among music lovers and subversives who see it as a romantic expression of political rebellion played out in musical form. It’s an idea that was born alongside the British Invasion -- and its oppression by the U.K. government, which aired only two hours of rock and pop music every week on the AM radio stations operated by the British Broadcasting Co. in the mid-’60s. That idea then spread to the U.S. and thrived underground for many years before reaching a fever pitch in the ‘90s and then, thanks to the democratizing Internet, largely died out.

I used to run KBLT -- a 40-watt pirate radio station that broadcast music 24 hours a day from my Silver Lake apartment from 1995 to 1998. So I was curious to see “Pirate Radio” and compare experiences. But the movie didn’t indulge that. Nor was it supposed to.

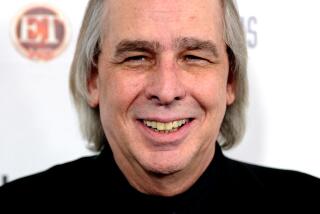

According to the film’s writer and director, Richard Curtis, a Brit who grew up listening to pirate stations with a transistor radio stuffed under his pillow, “I wanted to write a movie about pop music from the fan perspective. Then I remembered pirate radio and thought what a funny situation that was,” said Curtis, writer of the Hugh Grant comedies “Four Weddings and a Funeral” and “Notting Hill.” “Think of your most boisterous TV hosts today and tell them you’ve got to live in the same place. That was the film I wanted to write.”

And that is the film he did write -- pirate radio as sitcom, reconstructed from Curtis’ childhood memories. Among his recollections: that the DJs lived in the middle of the sea, that the British government shut most of them down, and that one of the stations continued to broadcast in defiance of the law -- all of which was accurate. It was in the hat changing from writer to director that Curtis sought an infusion of reality. And for that, he brought in Johnnie Walker, a real DJ from one of the era’s best-known pirates, Radio Caroline, in operation from 1964 to 1968.

In the film, Walker’s spirit is channeled by Philip Seymour Hoffman, who plays the Count, an amalgamation of many real pirate disc jockeys. The Count is the DJ who was on the air when the Marine Offenses Act went into effect, silencing most of the 20 seafaring stations that were in operation at the time. He was the DJ who told the government where they could put the new law and informed them that Radio Caroline would be continuing -- an act that has largely defined pirate radio’s enduring romantic and renegade legacy.

--

A real pirate DJ

In reality, that DJ was Walker, now 64. I reached out to him for his recollections, the back story to the fictional movie. “In the 1960s, to be a pirate DJ was about the most exciting thing you could do. It just had that romance of being out at sea and having to endure 10-knot gales and stuff like that,” he said. “The Beatles had happened and all the other great British bands like the Kinks, but the BBC just didn’t play that music, so the young people in England were absolutely dying to hear it.”

Walker was one of those young people. He was 21 and working as a club DJ in Birmingham when he went out on the water to join Radio England, then Radio Caroline -- a station that had been set up by an Irishman who’d bought a boat called the Mi Amigo, outfitting it with broadcast gear and re-christening it Caroline in honor of John F. Kennedy’s daughter.

According to Walker, Radio Caroline was supplied by another boat which motored the 1 1/2 hours from England’s Port of Harwich every day with letters, records, food -- and DJs, who were either coming to the ship after a week’s leave or going back to the island to soak up sounds at clubs such as the Speak Easy, where legends-in-the making Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton would play.

“Sometimes, you couldn’t wait to get back on the ship to play some great new record,” said Walker, who hosted the 9 p.m.-to-midnight shift, playing everything from the Animals to the Zombies.

There are quite a few parallels between the pirate radio of ‘60s England and the low-power FM radio movement that happened in the U.S. in the ‘90s, when hundreds of illegal micro radio stations cropped up around the country, including my own. Both movements were inspired by restriction. In the U.S., it was a lack of access to the FM airwaves, which are largely controlled by corporations that pay millions of dollars for the privilege. In 1993, Berkeley activist Stephen Dunifer sued the Federal Communications Commission claiming the corporations’ lock on the airwaves was a violation of his 1st Amendment right to free speech. His argument found a sympathetic ear in court for several years and gave rise to hundreds of stations that joined his fight and operated under the legal limbo he’d created using transmitters Dunifer distributed.

--

Land-based revolt

KBLT was one of those stations. Unlike the original English pirates, the U.S. movement was land-based and on the FM band. While many stations focused on politics, mine was, like the Brits, focused on music. Compared with ‘60s England, there was lots of music on the air in the ‘90s; I just didn’t think the radio offered a very good selection, which is why I opened my apartment to music fans of all stripes who played everything from hip-hop and country to swing, French pop and punk.

My station was financed with a $7 monthly fee paid by the DJs; the English pirates were funded with ads. Hindered by low power, my station had a reputation for having more DJs than listeners; the English pirates claimed to reach 20 million. While my station was my house, it wasn’t where the rest of the DJs lived. And where my station, in the end, was brought down by Dunifer’s court battle and an altercation with the FCC, Radio Caroline was toppled by expenses.

From August 1967 to March 1968, Radio Caroline was forced to operate from Holland, which drove up its operating costs. According to Walker, the Dutch company that supplied the crew was owed a lot of money, so they stole the boat. They arrived at 5 a.m. and cut the anchor chain and towed the Mi Amigo into Amsterdam to sell it.

“It was a very sad way for it to end,” said Walker, who like many pirate DJs found a job with the organization against which he had rebelled. Like the legendary John Peel, who began his DJ career as a pirate on Radio London, Walker joined the BBC.

Me? I was offered a job with the L.A. Times the same day I was busted by the FCC.

--

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.