Newsletter: California’s hottest, driest days are getting even drier, worsening fire risk

This is the June 17, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

If you live in the American West, you don’t need me to tell you it’s hot, hot, hot.

For the record:

5:19 p.m. June 17, 2021A previous version of this newsletter referred to a proposed Nevada lithium mine known as Thacker Pass facing a setback related to the Endangered Species Act. The proposed mine in question is Rhyolite Ridge.

Palm Springs set a daily record of 120 degrees this week. So did Anaheim, where the mercury hit 97. Salt Lake City tied its all-time temperature record, as did the Montana city of Billings. Las Vegas baked in 114-degree weather on Tuesday and was expected to be even warmer the next two days. The hills above Santa Clarita, north of Los Angeles, saw an overnight low of 87 degrees.

The California Independent System Operator warned that high nighttime lows and scorching temperatures across the West had led to tight electricity supplies, and issued a “Flex Alert,” urging people to use less electricity from 5-10 p.m. on Thursday. The grid operator said it didn’t expect rolling blackouts like we experienced last summer, although power shortfalls were still possible.

Even if the lights stay on, the intense heat will have other consequences.

As I wrote last summer, hot spells are deadlier than hurricanes and wildfires, with heat stress proving especially dangerous for vulnerable groups such as the elderly, outdoor workers, people without homes, families who can’t afford air conditioning and individuals with medical conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. High temperatures can also worsen air quality. Southern California officials issued an ozone advisory through Saturday, forecasting “very unhealthy” smog levels in some areas.

The invisible hand of climate change is hard at work here. Michael Wehner, a senior scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, estimates global warming has made rare heat waves 3 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer in most of the United States.

But temperature isn’t the only variable in flux. A new peer-reviewed study examines another one — humidity.

Led by UCLA climate scientist Karen McKinnon, the research team examined temperature and humidity data from 28 weather stations in California, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah. They found that between 1973 and 2019, a measure known as “specific humidity” decreased by about 22% on the hottest, driest days, after accounting for rising temperatures.

In other words, the Southwest’s hottest, driest days are much drier than they were a few decades ago. The numbers are even worse in California and Nevada, where humidity has dropped by one-third on those days over the last 40 years.

On the one hand, less humidity means less of a threat to human health, because wet heat makes it harder for the body to cool down. On the other hand, less humidity also means greater risk of fire, because parched vegetation is more flammable.

“We have both a temperature and a humidity signal going against us,” McKinnon told me. “That’s kind of the worst case, because it means when you already have these hot days, they’re unexpectedly and anomalously dry.”

The idea of humidity falling as temperatures rise may sound counterintuitive, because hotter air can hold more water. But that doesn’t appear to be happening on the Southwest’s hottest days. McKinnon and her coauthors attributed the trend to a decline in summer soil moisture, which means there’s less water on the landscape for plants to suck up and “transpire” into the air.

And why is there less summer soil moisture? Other scientists have linked that phenomenon to — you guessed it — climate change, with warmer weather causing more water and snowpack to evaporate off the landscape in winter and spring.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because we’re seeing the consequences right now. The West is drier than it’s been at this time of year since at least 2000, when a megadrought began. More than half the region was suffering exceptional or extreme drought conditions as of last week. Fires are burning in the mountains above California’s Coachella Valley and outside Flagstaff, Ariz.

“I don’t think we need more evidence saying that we should act on climate change, but here’s another piece adding to that puzzle,” McKinnon said.

I ran her study by water scientist Peter Gleick, president emeritus of the Pacific Institute think tank. He described McKinnon’s findings as “perfectly intuitive,” calling them “another fingerprint of human-caused climate change.” And while a future increase in summer rainfall — which is predicted by some climate models, and discussed in the study — could somewhat counteract the hot-day drying trend, “there would have to be significant increases in precipitation just to stay even,” Gleick told me via email.

I also talked with UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain, whose Twitter account is a must-follow for heat, drought and fire science.

Swain said a decline in “specific humidity” like the one found by McKinnon and her coauthors is especially alarming because it would widen the gap between the amount of moisture in the air and the amount of moisture the air can potentially hold. That gap is called the “vapor pressure deficit,” and the bigger it is, the more water the atmosphere will drink up from plants and trees.

As temperatures rise, the gap is growing because the air is capable of holding more moisture. That trend “is thought to be a major driver of why wildfires are becoming more intense,” Swain said, because it means the landscape is drying out faster than ever.

If absolute humidity is also getting lower, as McKinnon found, that means the gap will expand even more.

“This is actually suggesting that the problem is even bigger than a lot of folks had assumed,” Swain said.

This is an area where not a ton of research has been done, and McKinnon was careful to note that her dataset is limited to just over two dozen weather stations, all of them at airports, across a huge, diverse region. And the data only dates back to 1973.

At the same time, other analyses and data sources cited in the study, which was published today in the journal Nature Climate Change, suggest the same trend. Those analyses also suggest that most of the humidity decline has occurred since 2000.

So what can you, a regular person sweating in the ever-worsening heat, do about all this? For now, you can use less energy in the evening by setting your thermostat to 78 degrees or higher (if your health permits), pre-cooling your home, and using major appliances such as dishwashers, washing machines and electric car chargers in the middle of the day, when solar power is abundant.

Even more important, stay cool. If you don’t have air conditioning or can’t afford it, consider going to a cooling center or public library. My colleagues Faith E. Pinho and Lila Seidman also advise drinking more water than usual and checking on your neighbors.

Longer term, we’re going to need to stop putting carbon in the atmosphere, full stop. And as urgent as that may feel today, it will almost certainly feel more urgent later this summer, when California typically experiences its worst heat and fires.

For now, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

Lake Mead, the Southwest’s largest and most important reservoir, fell to a level not seen since it was first filled in the 1930s. The Colorado River water banked at Mead is dropping so quickly that it reached a record low four days earlier than federal scientists had projected just two weeks prior, the Arizona Republic’s Ian James reports. Californians don’t have to worry about Colorado River cutbacks yet, but they already face plenty of challenges from the hot, dry conditions, including increased fire risk and the potential for mandatory water restrictions in parts of the state, my colleagues Hayley Smith and Lila Seidman report.

Southern California is in better shape than Northern California when it comes to water supplies. Santa Clara County, home to Silicon Valley, is in an especially precarious position after its largest water provider was forced to drain its biggest reservoir last year because of earthquake risk that imperiled parts of Morgan Hill and San Jose, The Times’ Susanne Rust reports. State officials are also warning thousands of farmers, cities and others with post-1914 water rights that they must stop drawing supply from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta watershed due to insufficient flows, Rachel Becker reports for CalMatters.

Drought is hitting California’s farm country hard. CalMatters’ Julie Cart wrote about why agriculture is hurting, in a story that tracks how the San Joaquin Valley went from being “the greatest Artesian Basin in the world,” with water bubbling up from the ground, to a parched conundrum. One local official told Cart he’s heard as much as 20% of the region’s farmland is fallowed.

MORE THAN A DROUGHT

Water concerns are especially acute right now, but they’re a constant in the West. Take the fight over Southern California’s tiny rainbow trout, which my colleague Louis Sahagún chronicled this week, with beautiful underwater photography (and video!) by Carolyn Cole. An effort to save a native trout population from mudslides and fire debris by moving fish to the Arroyo Seco has come into conflict with the city of Pasadena’s plans to draw more water from the stream. In related news, the Biden administration says it will restore protections for millions of streams and other bodies of water, the New York Times’ Lisa Friedman reports.

Out in the desert, rising temperatures are evaporating limited water in the Amargosa Basin. The Amargosa River begins in southern Nevada and flows into Death Valley, running underground for much of its course. The river basin is believed to support the highest concentration of endemic species anywhere in the United States, Stefan Lovgren writes for National Geographic.

“Everybody thinks they’re special. But nobody is going to be very special when we run out of water.” Arizona, just like California, has a long history of pumping groundwater at unsustainable rates. Golf courses — yes, there are 165 of them in the Phoenix area alone, in the middle of the desert — are part of the problem. State officials want golf courses that use groundwater to cut back by 3.1%, and they’re not happy about it. They only want to cut back by 1.8%, Ian James reports for the Arizona Republic.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

A growing number of congressional Democrats say they wouldn’t support a bipartisan infrastructure bill (should such a thing ever materialize) that doesn’t include major climate investments. Here’s the story from The Times’ Jennifer Haberkorn. At least one climate-friendly infrastructure project is getting federal money either way; the Biden administration restored a $929-million grant for California’s long-delayed bullet train that President Trump had tried to take away, Ralph Vartabedian reports.

A federal judge ordered the Biden administration to keep selling oil and gas leases on public lands. The judge wrote that fossil fuel-producing states who sued to block President Biden’s leasing pause “demonstrated a substantial threat of irreparable injury,” per the Washington Post’s Joshua Partlow and Juliet Eilperin. In other Interior Department news, Secretary Deb Haaland has recommended that Biden restore the old boundaries of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments in Utah, reversing Trump-era cuts, the New York Times’ Coral Davenport reports. It remains to be seen what Biden will do.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

There was so much smoke from western wildfires last year that solar panels generated less electricity than usual. Canary Media’s Emma Foehringer Merchant writes that one Central Valley solar farm saw its output dip nearly 6% below average in 2020, and California solar production during the first two weeks of September was 30% below the summer average as smoke blocked the sun. Chalk this up as yet another way the warming world complicates the transition away from fossil fuels. It’s a cruel irony.

Plans to dig for lithium in Nevada are on hold while a judge considers a request from environmentalists to block excavation. Critics say Lithium America’s mine, which was approved by the Trump administration, would destroy sage grouse habitat; the developer says it’s needed to produce lithium for electric vehicle batteries and energy storage on the power grid, as Reuters’ Ernest Scheyder reports. Another proposed Nevada lithium mine, known as Rhyolite Ridge, also faced a setback when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said a rare wildflower should be protected under the Endangered Species Act, the AP’s Scott Sonner reports. Chalk this up as yet another way the transition away from fossil fuels can complicate other environmental priorities.

Mexico’s midterm elections could throw a wrench in President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s efforts to give more power to the country’s state-owned gas and electric companies. Critics say those efforts are crowding out renewable energy and slowing climate progress, so AMLO’s party losing seats in congress could have positive side effects for clean energy, the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Rob Nikolewski reports. But the president’s party will still control a majority of the Mexican government.

ONE MORE THING

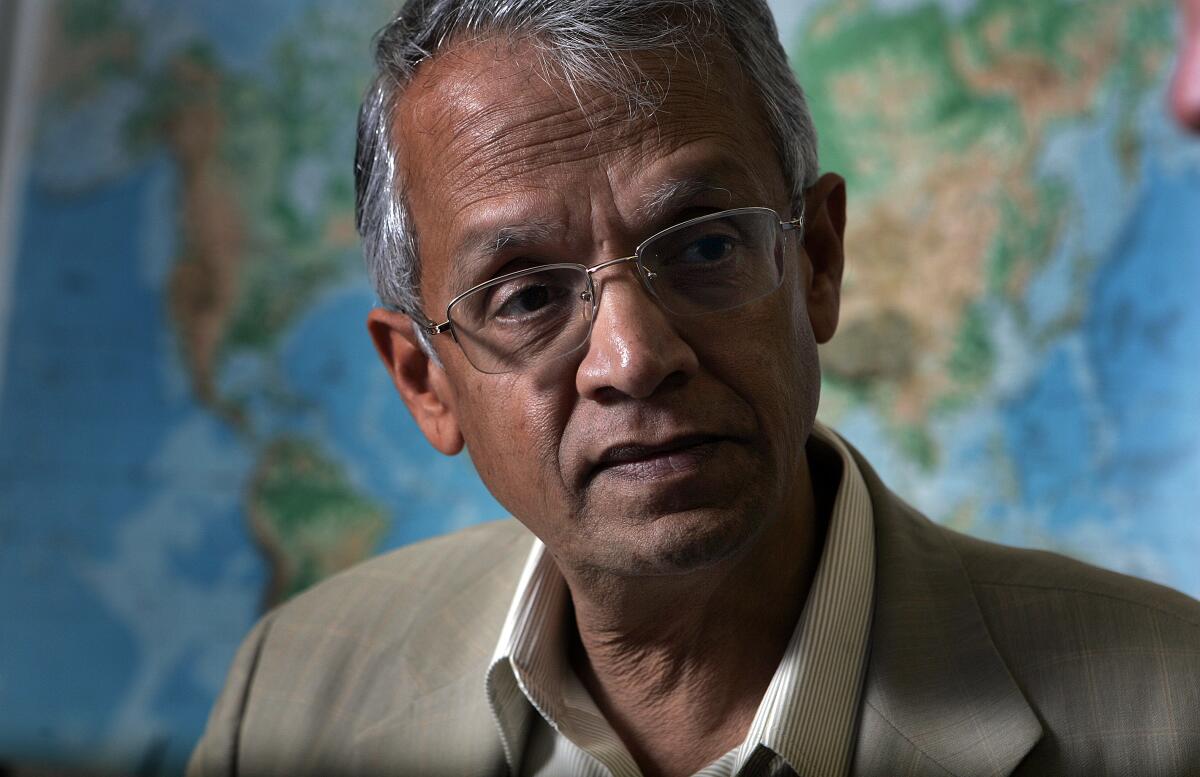

Veerabhadran Ramanathan has been studying the greenhouse effect since the 1970s, so it makes sense that he’s “really upset” we haven’t solved the problem by now. The San Diego-based scientist was just honored with the prestigious Blue Planet Prize, and he told the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Joshua Emerson Smith that it’s hard to celebrate when temperatures keep going up.

At the same time, Ramanathan thinks humanity can still avoid the worst consequences of global warming by quickly slashing emissions of climate “super pollutants,” such as methane from fracking and hydrofluorocarbons from refrigerants.

“Many young people think it’s hopeless, but it’s not,” Ramanathan said. “We still have time.”

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.