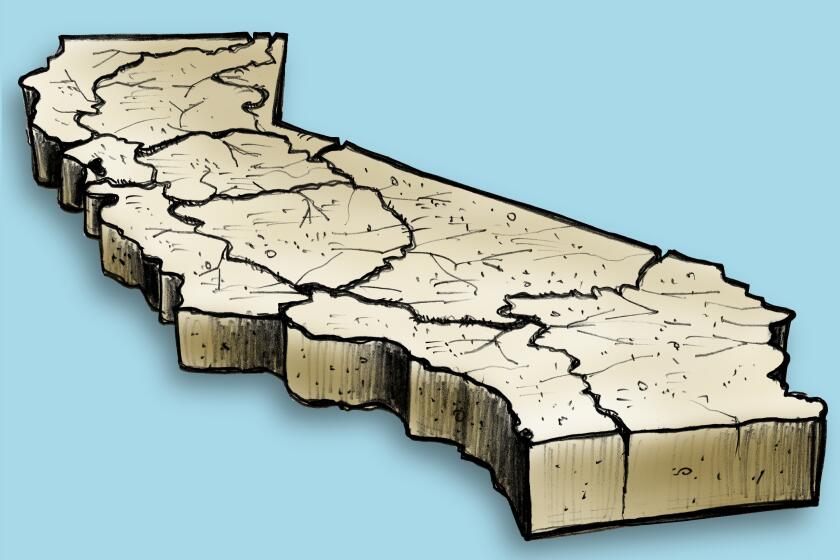

California suddenly has so much snow. But even this extraordinary bounty isn’t enough

At the UC Berkeley Central Sierra Snow Laboratory in Donner Pass on Wednesday, snow was piled so high that lead scientist Andrew Schwartz no longer needed stairs to exit the second floor.

“We just walk directly out onto the snow!” Schwartz said. The nearly 11 feet of snow surrounding the lab was the deepest he’d seen so far this year.

The piles of powder are the result of a series of powerful atmospheric river storms that have pummeled California over the last two weeks. The storms have claimed at least 19 lives as they topple trees, overtop levees and send people scrambling for higher ground.

But while the storms have delivered chaos, they have also helped to make a dent in drought conditions. The state’s snow water equivalent — or the amount of water contained in the snow — was 226% of normal on Wednesday, marking a high for the date not seen in at least two decades.

The powerful storm that knocked out power, toppled trees — including one that killed a toddler — and flooded homes along the coast in Santa Cruz continued its march through the region.

The last time snowpack neared such a high on Jan. 11 was in 2005, when it was 206% of normal, according to state data.

Even more promising, the Sierra snowpack on Wednesday measured 102% of its April 1 average, referring to the end-of-season date when snowpack in California is usually at its deepest. This is the first time that’s happened on Jan. 11 in at least 20 years.

“102% of average with another week of stormy weather coming up is absolutely fantastic,” Schwartz said. “And assuming we don’t see complete and absolute dryness like we did last year, it’s shaping up to be a winter that, at the very least, will prevent us from going into further drought, if not help pull us out of the drought.”

But Schwartz and other experts were cautious about celebrating too soon. The measurements are not static and could change depending on how the rest of the wet season develops. Last season, for example, a soggy December gave way to a bone-dry January, February and March.

Forecasters say it’s too soon to be certain what the coming months will bring. Mike Anderson, state climatologist at the Department of Water Resources, said two more atmospheric rivers were heading for California before conditions are expected dry up around Jan. 20.

Longer-range forecasts are fuzzier, he said, with the latest seasonal outlooks from the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center showing equal chances of wetness or dryness in most of Northern California through March. But there is a chance of one more atmospheric river to close out January.

“We’re definitely looking to be in a better situation than we were last year, where everything shut off for a good three months, and there will be that opportunity to continue to make some additions to that snowpack before we get to April 1,” Anderson said.

The latest storm further swamps California, already reeling from widespread flooding, mudslides, washed-out roads and downed power lines.

DWR water operations manager Molly White said reservoirs were also seeing boosts from the storms, with some smaller reservoirs recovering fully from drought-driven deficits. But the state’s two largest reservoirs, Lake Shasta and Lake Oroville, remain far from full, topping out at 42% and 47% of capacity, respectively, on Wednesday.

“Storage right now is still less than where they were back in 2021, but better than where they were in 2022,” White said. “We’ve had quite a deficit because of the drought, so we’re seeing steep inclines right now in storage, and hope that continues as we see these storms and that we can get back to above average.”

The atmospheric rivers also haven’t had much effect on Southern California’s other major water source, the Colorado River, which remains at perilous lows. The river’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead, was 28% full at its last weekly measure.

“It’s just really important to remember that we are in a continued drought emergency,” said DWR spokesman Ryan Endean. “We’re kind of dealing with this extreme flood during an extreme drought, and so we’re, of course, encouraging Californians to continue to conserve water and make conservation a way of life.”

Although rain is helpful, it’s snow that holds the most value for the state’s water supply, said Schwartz, of the Berkeley Snow Lab. While rainfall comes in pulses that can sometimes lead to massive amounts of flooding or be difficult to capture, snow melts slowly and provides a constant source of water, especially in warmer months when it’s needed most.

The deadly toll from California storms grows to 18

That’s why water managers tend to think of snow as a reservoir in and of itself, he said. But like water, too much snow can also pose a threat. When rain falls on snow, it can create ice layers or even make the snow too heavy, which can potentially give way to avalanches.

“With all these different storms, as more and more snow piles up, the likelihood of more avalanches goes up pretty substantially, especially when it doesn’t have time to settle between storms,” Schwartz said.

But powerful, potentially dangerous weather is often the way California gets out of drought, said John Abatzoglou, a professor of climatology at UC Merced.

“Historically, drought recovery in California has come with atmospheric rivers,” he said. “That is sort of a recipe for drought recovery — it is a great elixir for drought, in terms of dealing with surface water woes, but the downside is too much of a good thing at once.”

The latest maps and charts on the California drought, including water usage, conservation and reservoir levels.

Abatzoglou said Wednesday’s snowpack levels were impressive, and noted that the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor update saw the worst category, “exceptional drought,” erased from California’s map altogether. Only a week before that update, more than 7% of the state was in that category.

And although surface water conditions are starting to improve, the state’s combined snow and reservoir measurements are still about 8 million acre-feet below normal for April 1. An acre-foot is about 326,000 gallons.

“Drought is so complicated, because when you think about the impact of drought on groundwater, there’s no way that’s going to be recovered this year,” Abatzoglou said. The Central Valley has “effectively lost something like 1½ Lake Mead’s worth of groundwater over the last 20 years.”

The state’s aridifying climate is also making it more challenging to hold on to water over time. Dry soils and a thirstier atmosphere demand more moisture, which can rob the state of its ability to convert “snow to flow,” he said — although conditions are so saturated from the recent storms that that may be less of a problem this year.

“It is this paradox of our reservoirs are still underfilled, especially the really large ones, and yet we have so much water coming in a short amount of time,” Abatzoglou said.

He added that most of California has missed out on about a year’s worth of precipitation over the last three years of drought. Although the rain and snow are helping, more is needed.

“We have this huge bucket we’re filling, and we’re filling it super fast,” Abatzoglou said. “But there’s still a way to go for achieving true recovery from drought.”