J.R.R. Tolkien’s ‘Fall of Arthur’ and the path to Middle-Earth

The books go ever on and on. Forty years after his death at 81, works by J.R.R. Tolkien continue to appear. The latest, “The Fall of Arthur,” lists nine works published during his lifetime (“The Lord of the Rings” trilogy appears as a single title) and 24 posthumously, including the 12-volume “History of Middle-Earth,” edited by Tolkien’s son and literary executor Christopher.

After his father’s death, Christopher left his own position at Oxford to devote his life to Tolkien’s vast oeuvre. In addition to the mammoth “History,” Christopher edited “The Silmarillion” and volumes of Tolkien’s letters, essays, unfinished stories, artwork, children’s tales, scholarly works and now a never-before published fragment of a long narrative poem that draws on the Arthurian legends.

“Tolkien has become a monster, devoured by his own popularity,” Christopher said in a 2012 interview with Le Monde. “The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work, and what it has become, has overwhelmed me.”

Yet few things seem more overwhelming than the task Christopher undertook in organizing the massive archive his father left at his death — 70 boxes of unpublished tales, notes, fragments and drawings — and making it accessible to a popular readership.

This seems even more of a challenge today, when the material directly related to Middle-earth appears to have been pretty thoroughly strip-mined. The most recently published book, “The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun” (2009) was Tolkien’s verse retelling of stories from the ancient Norse Eddas. Now in the newest addition to the Tolkien canon, Christopher has provided an exegesis of a long unfinished poem: “The Fall of Arthur,” a narrative told in alliterative verse and inspired in part by a 14th century text known as “Morte Arthure.”

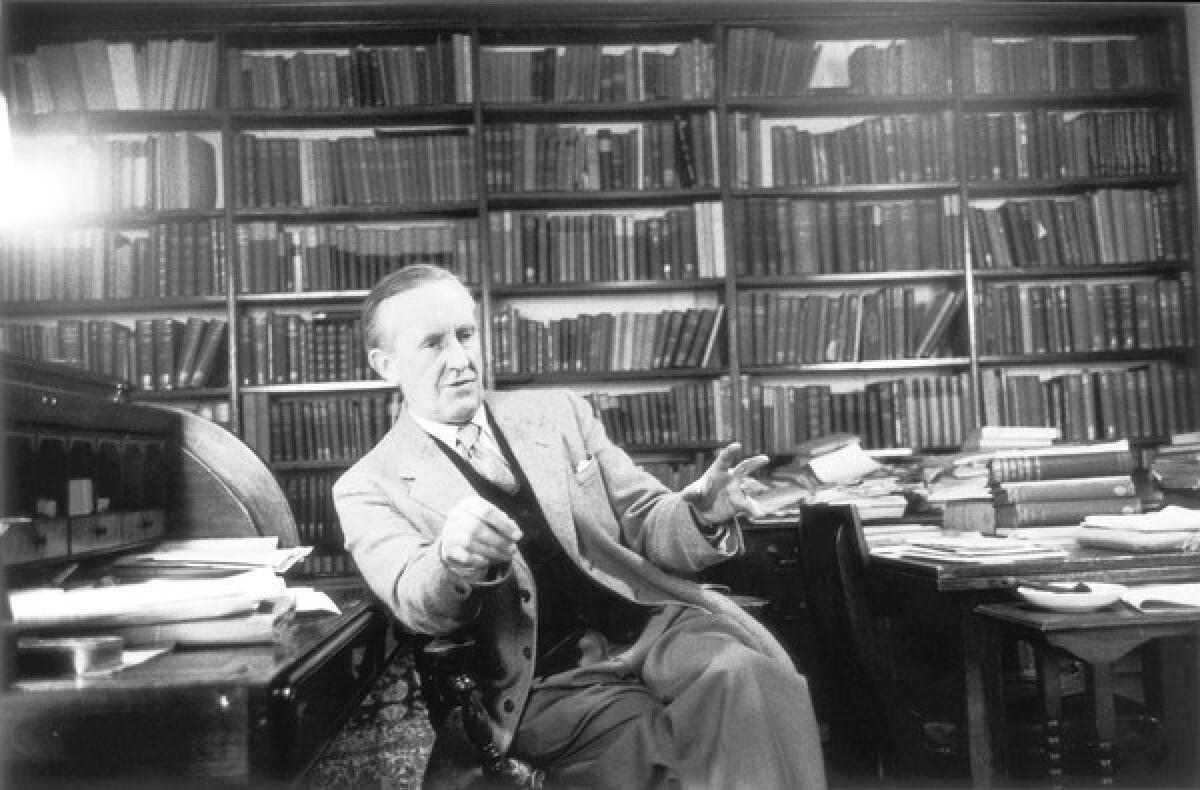

Tolkien was a noted scholar and linguist before he was a published novelist, laboring on the Oxford English Dictionary and then embarking upon a long career at Oxford University, where he was professor of Anglo Saxon studies and later Merton Professor of English, a chair he held until his death. His iconoclastic 1936 lecture, “Beowulf: The Monster and the Critics,” challenged assumptions that the eighth century text should be treated purely as a historical document and not a work of art. It’s now regarded as a watershed moment in Beowulf studies.

In the essay, Tolkien didn’t mince words in his disdain of fellow academics: “For it is of their nature that the jabberwocks of historical and antiquarian research burble in the tulgy wood of conjecture, flitting from one tum-tum tree to another.” He was particularly dismissive of those who ignored the importance of the poem’s monsters — Grendel, Grendel’s mother and especially the dragon that Beowulf kills, but not before he himself is mortally wounded.

“A dragon is no idle fancy,” Tolkien observed. “There are in any case many heroes but very few good dragons.”

He later took it upon himself to correct this sad situation, in the novels of Middle-earth. But in addition to “The Lord of the Rings” and his other better-known work, Tolkien also wrote a considerable amount of poetry inspired by Old English and Middle English texts — “The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son,” “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” “Pearl,” and “Sir Orfeo,” in addition to the Norse-inflected “Sigurd and Gudrun.”

“The Fall of Arthur” is a fascinating work, though perhaps more for the Tolkien completist than the casual “Lord of the Rings” fan. Christopher Tolkien can’t pinpoint when his father began to write it: The earliest reference is in a 1934 letter from the scholar R.W. Chambers, a friend of Tolkien’s, who details how he read part of the poem on the train to Cambridge (and on the return trip took over an empty carriage to read it aloud).

“It is very great indeed,” wrote Chambers; “really heroic, quite apart in its value in showing how the Beowulf meter can be used in modern English … You simply must finish it.”

What survives of the poem’s actual text takes up only 57 pages of this newly published volume. It focuses on the bloody aftermath of Queen Guinevere’s affair with Lancelot, greatest of Arthur’s knights, and is surprisingly powerful in its terse depiction of the affair’s devastating consequences. The style will be familiar to anyone who’s ever been captivated by the narrative verse that embellishes “The Lord of the Rings.”

Dear she loved him

with love unyielding, lady ruthless,

fair as fay-woman and fell-minded

in the world walking for the woe of men.

The poem also features a rare Tolkienian display of erotic obsession, in the lust that Arthur’s son, Mordred, harbors for Queen Guinevere. “Towers might he conquer,/ and thrones o’erthrow/ yet the thought quench not.”

Most contemporary retellings of the Arthurian cycle focus, unsurprisingly, on the lovers’ illicit passion. But Tolkien emphasizes Lancelot’s (nonromantic) love for Arthur, his sense of duty and remorse. After Guinevere flees Mordred, Lancelot rescues the Queen, yet there is no joyous reunion between the two:

By the sea stood he

as a graven stonegrey and hopeless.

In pain they parted.

Neither is there forgiveness for the knight who betrayed his liege. “Grace with Arthur/ he sought and found not.”

The remainder of “The Fall of Arthur” is devoted to Christopher Tolkien’s detailed commentary on the poem’s influences and evolution and various drafts, its place in the Arthurian tradition, and the relationship between Tolkien’s notes for the unwritten poem and its relation to “The Silmarillion.” The latter is by far the most intriguing. A complex analysis of Tolkien’s use of lost islands — Avalon, Avallon, Numenor, Atlantis, Tol Eressea — it links the Arthurian poem not just to Tolkien’s later work but also to a recurring motif in his fiction.

Part of the attraction of “The Lord of the Rings,” he wrote in a letter, “is, I think, due to the glimpses of a large history in the background: an attraction like that of viewing far off an unvisited island … To go there is to destroy the magic, unless new unattainable vistas are again revealed.”

Christopher Tolkien speculates as to why his father might have stopped work on “The Fall of Arthur.” He names “the demands of his position and his scholarship and the needs and concerns and expenses of his family … he never had enough time …” Yet it’s just as likely that, during his exploration of the Arthurian cycle, Tolkien caught glimpses of the “new unattainable vistas” that would ultimately comprise his own Legendarium.

In a 1951 letter he wrote, “I was from early days grieved by the poverty of my own beloved country: it had no stories of its own (bound up with its tongue and style) not of the quality I sought … I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic, to the level of romantic fairy story … which I could dedicate simply: to England: to my country.”

Over a lifetime, Tolkien constructed that legendarium and in doing so single-handedly created a modern mythos arguably as influential as the medieval Arthurian epic that was one of its inspirations. “The Fall of Arthur” is an important harbinger of the great work that was to come.

Hand’s most recent book is the collection “Errantry: Strange Stories.”

The Fall of Arthur

by J.R.R. Tolkien

Edited by Christopher Tolkien

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: 233 pp., $25

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.